After disassembling my retired Philips Sonicare (HX6530) enough to access its internal circuitry, I paused to take a look at it under my oscilloscope. After completing that detour, the oscilloscope probes were put away, and the mechanical tools came back out to resume disassembly.

First to be freed was the circuit board. In addition to a few plastic clips (and one melted plastic rivet) it was held with six soldered connections: Two wires for the actuator coil, two for the battery, and two for the charging coil.

From left to the right, here are the components I recognized on the board:

- A single green surface-mount LED, the only user visual feedback on this device

- A single button, the only user input.

- Six large pads. There’s solder on Rx and Tx because I wanted to see if it was transmitting serial data. (It did not.) Two of the pads are labeled Gnd and they both electrically connected to ground. The remaining two pads are labeled Vdd and Vpp, and I don’t understand how they differ. They both seem to show the current battery voltage.

- Two resistors R1 and R3, then the two Alpha & Omega field effect transistors Q1 and Q2.

- Two more resistors R5 and R4, than the two pads leading to actuator coil.

- A through-hole for the battery positive terminal, leading to F1 and an unoccupied pair of pads. The component sitting at F1 has a small “P” printed on it and it doesn’t look like a resistor. Thinking of electronic things that start with “F” and would make sense at the battery terminal, I think this is a safety fuse. The unoccupied pair of pads has a thin trace connecting them. I guess this is a provision to put something in line with battery power: we can cut that trace then solder something on those pads.

- U1 is the Microchip PIC16F726 microcontroller.

I got lost after this point. There are many unpopulated pads, I presume features for higher end models. SW2 would be for another switch, but what might sit at BZ1? Some of these components would deal with power coming in from the charging coil (connected at the holes on either side of the CR6 lettering) and maybe for battery management. The positive battery terminal connection point was mentioned earlier, the negative terminal connects to the upper-right hole adjacent to lettering JP1.

Speaking of the battery, unsoldering its connection to the circuit board freed it from the chassis. Now we can read the lettering on its side telling us it is a 14500 form factor (14mm diameter, 50.0mm length) cylindrical cell with a capacity of 680mAh (milli-Amp hours).

The charging coil stayed on the black rigid plastic chassis, but now that it is freed from the circuit board I hooked it up to the oscilloscope again for another look.

Left plot was taken while the charging coil was connected to the circuit board, right plot is the coil by itself. Note the vertical scale has changed between these two plots: 1V/div on the left and 5V/div on the right. The most obvious difference is the shape: it is now a sine wave instead of a square wave. The amplitude is much larger at about 30V peak-to-peak or 15V above and below the center point. This is roughly triple the rectified 5V I saw earlier. I don’t know enough about analog electronics to know what would accomplish this on the now-removed circuit board, maybe in the future.

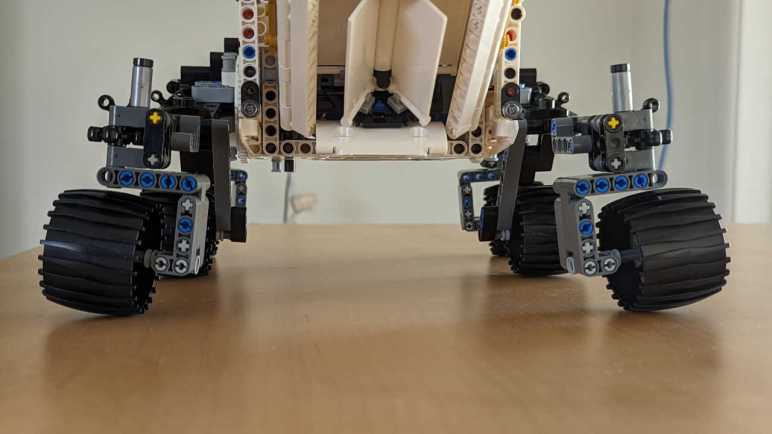

With the electronics disassembled, my attention returned to the electromechanical actuator assembly.