After wrapping up a thermal camera project, my mind turned to other things I can’t see with my unassisted eyes. So I revisited the market of affordable digital microscopes and decided to try an Andonstar AD246S-M (*). Verdict: I’m happy with my purchase, but knowing what I know now, a cheaper option would have been fine.

Previously…

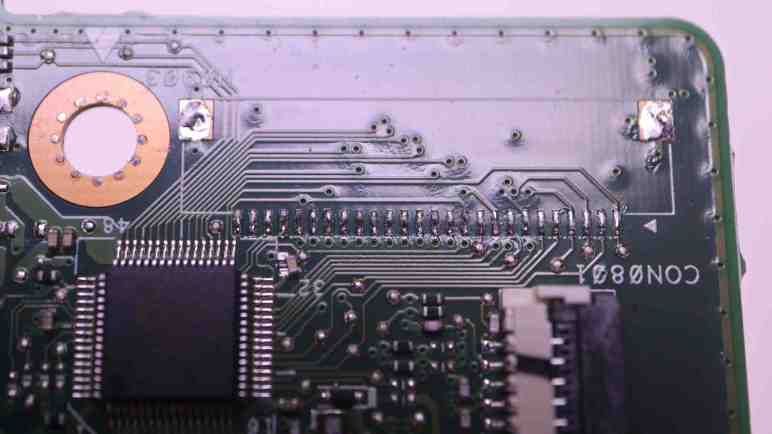

Years ago I bought a cheap microscope (~$30 *) which acted like a webcam when plugged into my computer. Except instead of showing my face for a video conference, it showed whatever I could bring into focus for magnification. Appropriate for the price point, it was a neat toy but not a great microscope. I think the native sensor resolution was at most 640×480, the optics were not sharp, and the ring of illumination LEDs surrounding its lens caused a lot of glare. And that’s when it worked properly! After some use, my unit started locking up whenever I brought the picture into focus. I hypothesize there was a problem with data processing or transmission. A blurry picture compresses well and doesn’t require much bandwidth to transmit. A focused picture demands more and apparently too much for the the thing to handle. A microscope that runs only when out-of-focus is useless, so it ended up as teardown fodder for 2019/10/15 session of Disassembly Academy.

Market Survey

But I liked the idea enough for another try. Looking at Amazon listings for “digital microscope”, I see the cheap toy is now only about $20. I’m willing to spend more for a better product, what will I get for my money?

- Listings over $30 usually have a sturdier stand. This is not a big deal, I can build one if it’s important to me.

- Listings over $60 have integrated screens. I like the idea of standalone operation. If the USB connection craps out, it’s still a functional tool. Add-on features like adjustable stands and LED illumination start coming into play, but as they’re not core to the electronics they’re things I can do myself.

- Listings over $90 start talking about 1080P resolution, implying the cheaper options are lower resolution. They also start integrating features like an HDMI-out port and saving pictures to a memory card, stuff I can’t add on my own later. (In hindsight, this is the sweet spot.)

- Listings over $120 start offering interchangeable lenses. Interchangeable lenses would give me more options now, and leave the door open for future projects in optical experimentation. (Andonstar’s AD246S-M slotted here in my hierarchy.)

- Listings over $150 seems to be past the point of diminishing returns. For example, some have screens 10″ diagonal or larger, which isn’t as important when I can connect even larger screens via HDMI. We also get into quality improvements that are difficult to filter on Amazon. Quantifying lens quality is complicated. Same for camera sensitivity and dynamic range, etc.

I decided I didn’t know enough to judge improvements offered by products over ~$150. The listings continue all the way up to microscopes costing many thousands of dollars. Personally I wouldn’t buy any of those from random Amazon vendors, at those price points I’d rather buy from a known vendor of industrial/scientific equipment.

I’m here in the cheap end, where lenses are probably plastic and resolution claims are highly suspect. I am willing to believe claims of up to 1080P, as there exist lots of inexpensive webcam sensors and screens at 1080P, but anything higher is likely interpolated. Andonstar AD246S-M claimed UHD, a claim I doubt, but the rest of it looks interesting enough for me to try.

(*) Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.