After wrapping up my adventures in Xbox One SSD upgrades, I decided to stay on the theme of storage devices and dug up this old thing from my pile of hardware awaiting teardown.

This device looks ancient but Fantom Drives appears to be still around today. Or possibly a company has acquired rights to that name and logo for doing business. The website lists a few internal M.2 SSDs but most of the product line are external USB storage drives. This is likely an early product of that line.

Size of this enclosure is consistent with a single 5.25″ floppy (or CD-ROM or DVD) drive bay. However, the front faceplate is empty with no slot for a disk.

Around the back we see a plug (IEC 60320 C13/C14) for power and a USB plug (type B) for data. A power switch and cooling fan rounds out the plate. I found the fan curious, because I don’t see any grille for intake or exhaust on this enclosure. Airflow would have been limited at best.

I see four screws on this plate. Two of them holds the fan in place, and the other two probably holds the USB data translation system in place. Neither look like a way for me to open up the box.

Four screws are visible on the bottom, and again they don’t look like something that’ll let me open the enclosure. They probably hold the storage device within.

I’m sure the warranty is long gone on this device, but I’m thankful for this “Warranty Void if This Seal is Broken” sticker because they would have placed it in a location critical to disassembly. Which is where I should start.

After the sticker was removed, the dark plastic clips on either side could be removed, allowing top and bottom enclosure halves to separate. Inside the enclosure we see… a standard 3.5″ hard disk drive looking pretty small inside that enclosure. It has a capacity of 80GB, giving an idea of how old this thing is. Nowadays we can buy cheap microSD cards with more capacity.

Another hint of its age is the antiquated parallel ATA interface used by this drive. I remember working on old PCs, fighting these huge and unwieldy cables. I do not miss them. Modern SATA (serial ATA) is so much easier to work with.

The spindle motor on this hard drive caught my attention: it is connected with four wires and not three like the hard drive motor I tried to turn into a generator. Could this be a pair of windings for two independent sets of coils? If so, I might try to run this thing using a stepper motor driver just to see what happens.

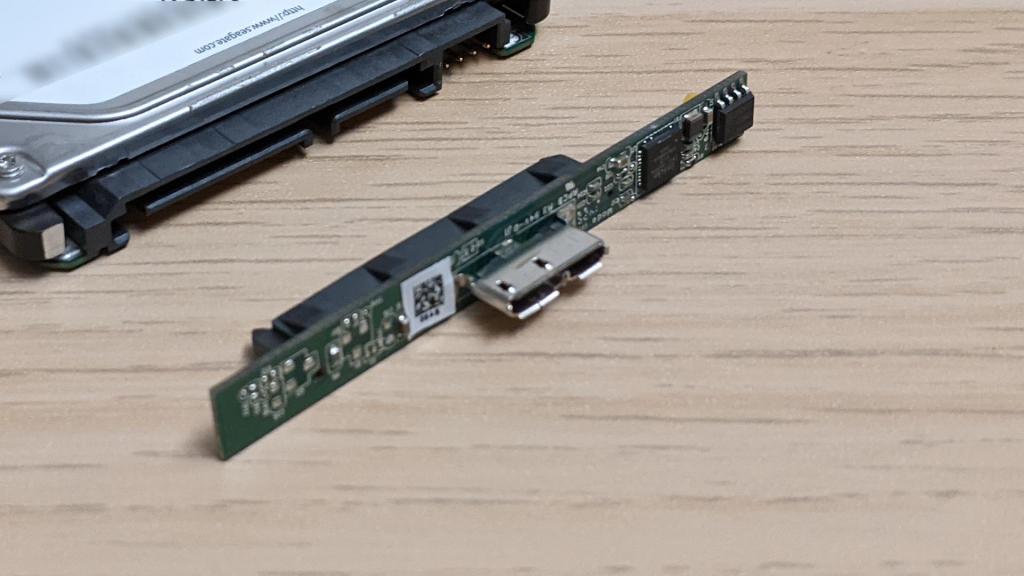

As for the electronics, I don’t know if I will ever find use for a board that translates between USB2 and PATA, two old and slow interfaces. The power supply is more likely to find reuse. I have a sizable stockpile of wall warts including several units with 12V DC output and several with 5V DC output. However, this particular power supply might come in handy if I ever need 12V and 5V together.

But back to that four-wire motor: what’s going on over those wires?