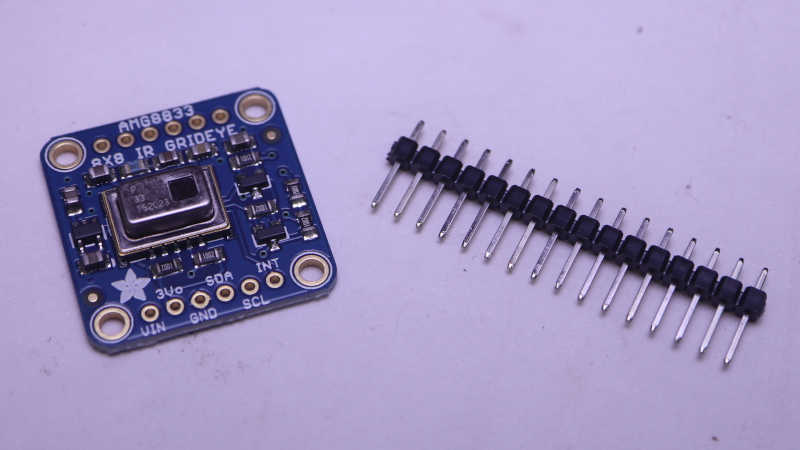

The AMG8833 thermal sensor I taped to an Adafruit Memento camera is successfully communicating with the ESP32-S3 microcontroller running Memento, and I can start working on integrating data from both thermal and visual cameras.

Goal

Low resolution thermal data can be difficult to decipher, but overlaying low-resolution thermal data on top of high-resolution visual data helps provide context for interpretation. This is a technique used in commercial thermal imaging products. The most accessible devices are designed to plug into my cell phone and utilize the phone for power and display. For my Android phone, it’ll be something like this FLIR One unit.(*) I’ve thought about buying one but never did. Now I will try to build a lower-cost (though far less capable) DIY counterpart.

Precedence

For code functionality, there’s a useful precedence in Adafruit’s “Fancy Camera” sample application: it has a stop-motion animation mode which shows the previously captured frame on top of the current viewfinder frame. This allows aspiring stop-motion animators to see movement frame-to-frame before committing to a shot, but I want to try using its overlay mechanism for my purposes. On the source code side, this means following usage of the data objects last_frame and onionskin. They led me to bitmaptools.alphablend(). Performing alpha blending on a microcontroller is not fast, but it was a good enough starting point.

Drawing Thermal Overlay

Now that I’ve found a helper to blend the viewfinder image with my thermal data, I have to draw that thermal data. The small LCD on board Memento has a resolution of 240×240 pixels, and that divides neatly into 8×8 sensor resolution. Each sensor data point corresponds to a 30×30 pixel block of screen. Drawing solid squares was really, really slow. I opted to draw every third pixel vertically and horizontally, which means drawing a dot for every 3×3=9 pixels. This lent a screen door effect to the results that was, again, good enough as a starting point.

Thermal Color Spectrum

Commercial thermal cameras have established a convention for color spectrum representing thermal data. Black represents cold, blue is a bit warmer, then purple, red, orange, yellow, all the way to white representing the hottest portion of the picture. I started mapping out a series of RGB values before I noticed that spectrum is conveniently half of a HSV hue wheel. I went looking for a CircuitPython library for HSV color space and found FancyLED. Calling pack() gave me a representation in RGB888 format instead of the RGB565_SWAPPED format used by Memento LCD. I didn’t find an existing conversion utility, but I’m a C programmer and I’m comfortable writing my own bit manipulation routine. It’s not the fastest way to do this, but I only have to build my palette once upon startup so it’s not a concern for the performance-critical inner display loop.

# Obtain hue from HSV spectrum, then convert to RGB with pack()

rgb = fancy.CHSV(hue, saturation, value).pack()

# Extract each color channel and drop lower bits

red = (rgb & 0xFF0000) >> 19

green_h3 = (rgb & 0x00FF00) >> 13

green_l3 = (rgb & 0x003800) >> 11

blue = (rgb & 0x0000FF) >> 3

# Pack bits into RGB565_SWAPPED format

rgb565_swapped = (red << 3) + (green_h3) + (green_l3 << 13) + (blue << 8)

Orientation

I was happy when when I saw my thermal color overlay on top of the viewfinder image, but the two sets of data didn’t match. I turned on my soldering iron for a point source of heat, and used that bright thermal dot to determine my thermal sensor orientation didn’t match visual camera orientation. That was easily fixed with a few adjustments to x/y coordinate mapping.

Field of View

Once the orientation lined up, I had expected to adjust the scale of thermal overlay so its field of view would match up with the visual camera’s field of view. To my surprise, they seem to match pretty well right off the bat. Of course, this was helped by AGM8833’s low resolution giving a lot of elbow room but I’m not going to complain about having to do less work!

Too Slow

At this point I had a first draft that did what I had set out to do: a thermal overlap on top of visual data. It was fun taking the camera around the house pointing at various things to see their thermal behavior. But I’m not done yet because it is very sluggish. I have plenty of room for improvement with performance optimization and I think TileGrid will help me.

(*) Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

https://github.com/Roger-random/circuitpython_tests/commit/30e24717cad579a0cc05f4b381d5f637259fe4bb