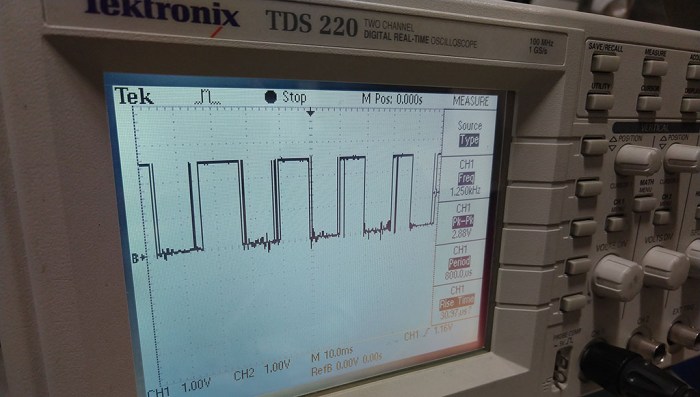

The jagged wave form of the encoder signal was diagnosed to the plastic filament used to print the encoder wheel. It was opaque to visible light but the infrared light used by the optical encoder could penetrate enough to trigger false transitions. Reprinting the encoder wheel with a different plastic resulted in clean encoder square wave form confirmed under an oscilloscope.

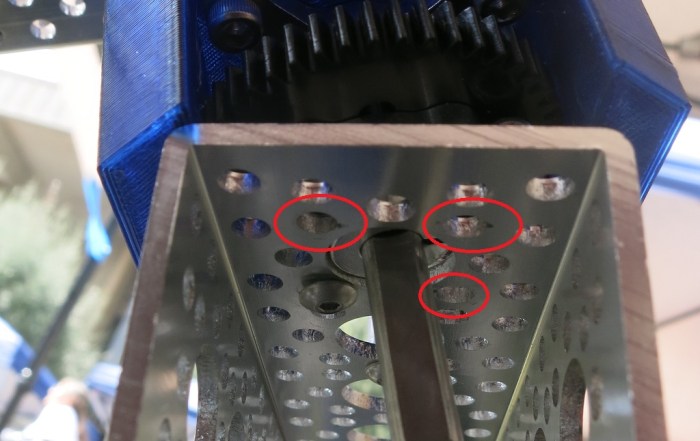

The planetary gear updated with the encoder is unfortunately correlated with a new problem: the automatic PID tuning algorithm in Ion Studio stopped working. Whenever the tune button was pressed, a few motor movements would occur in the first half second or so, then the software freezes up. Status LED on Roboclaw stopped blinking, confirming that communication between the software and the control board broke down. The motor continued spinning according to the last instruction it received. Terminating Ion Studio was not enough to release the serial port and Windows had to be rebooted. A reset of the Roboclaw back to factory configuration did not change this behavior, nor did switching to another Windows machine with Ion Studio.

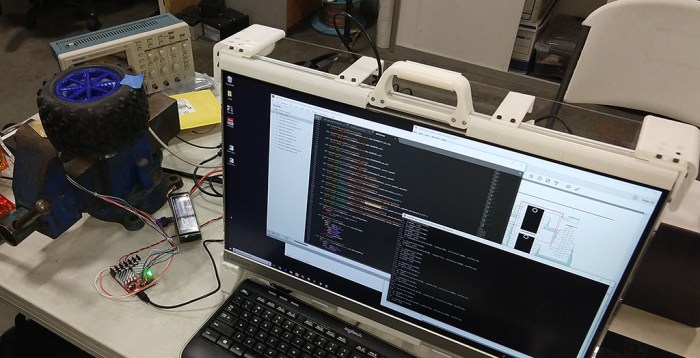

An Ion Motion Control forum post implied a faulty encoder could cause this problem, but the encoder looks good to us under the oscilloscope. With little other information to diagnose with, we had to fall back to manual tuning of the PID control loop. This is a common task in building motion control systems, with scholastic research on how to obtain the best values. But with some basic understanding of PID control it’s possible to manually get close enough to proceed with the project.

A challenge of tuning PID systems comes from the fact the values have no standardized units. A good proportional (P) gain might be 6.0 in one PID system and another system would want 400. Ion Motion Control documentation for Roboclaw didn’t seem to have any guidelines on the number range we should expect to use, just that each value in the API is represented by a 32-bit integer.

The default values on a freshly reset Roboclaw is zero, which is obviously not going to work. Lacking any guidance, we started with setting proportional gain (P) to one and left the rest at zero. This took several seconds to start turning the wheel. Setting P to ten, then 100, increased the response rate. At 1000, we saw oscillation of the motor as it raced too far ahead, then backtracked too far, then forward too far again. This is a symptom of P set too high, so this gives us a starting range of somewhere in the hundreds.

The freshly 3D-printed planetary gears added an unforeseen challenge. They have yet to wear in to each other and still have some rough spots. Combined with a tight fit (by design, to minimize backlash) this translated to high stiction requiring more power sent to the motor before it would start turning. At the moment, the wheel is spinning in open air and required little power to keep turning once it started. The large difference between startup power vs. runtime power translated to a tendency to overshoot on startup. This behavior is visually similar to a too-large P value and hard to tease them apart when tuning manually.

A well-tuned PID control system could handle this properly, but we’re not there yet. In the short term, the plan is to put these wheels on a test chassis so we could see how it works as actual propulsion. Also, installing the wheel on a chassis (and putting a workload on it) would increase the power needed to keep the wheel turning. Narrowing the difference between startup power and runtime power will hopefully help make fine-tuning the control loop easier.

The rover made an appearance in the local news

The rover made an appearance in the local news