I don’t know what’s involved in maintaining an inkjet cartridge, but I’m learning bits and pieces by poking around inside my retired Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet. I saw where the print head would rest when in its parked position, and thought the rectangular block of material sitting underneath the print head would be something soft and spongy to absorb excess ink. I was surprised when I poked at it with a cotton swab and found it was rigid. Interesting! Now I’m even more curious and want to see the rest of this maintenance assembly.

Looking at how its multiple parts interlocked, I came to the conclusion this one screw holds down everything on front side of this assembly. Removing the screw allowed this piece of plastic to slide aside and be removed.

This assembly hosts the latch that makes the wiper blades work, and it covers one side of the up-and-sideways track for the maintenance assembly allowing me to flip it up.

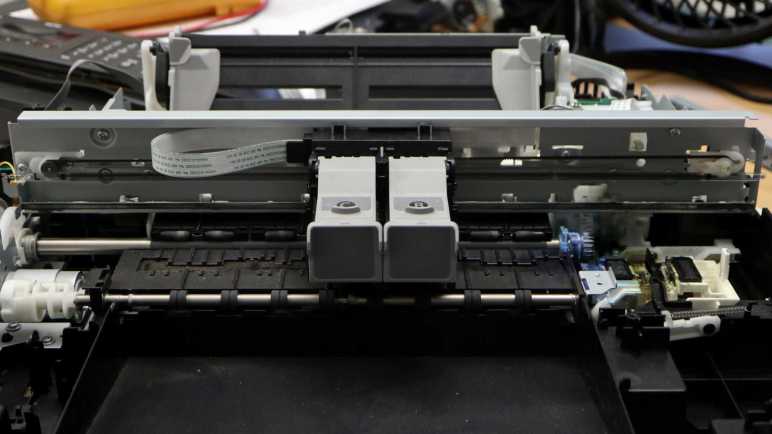

Now I can see the motion mechanism in its entirety. There are four tracks to guide this assembly as it moves 45-degrees up and then right, and in the foreground of this picture is the retraction spring pulling it down and left.

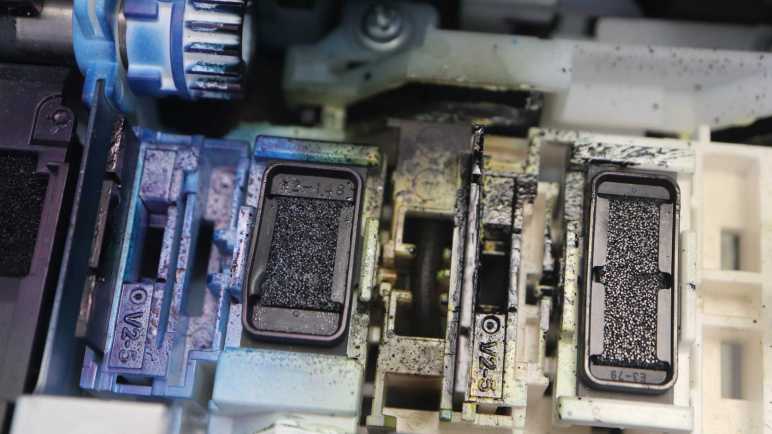

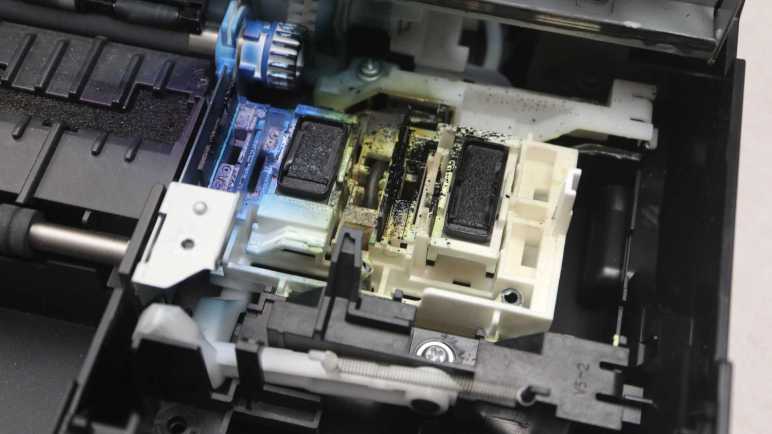

Each ink cartridges sit over a spring-loaded assembly with a tube in the middle. These springs push the pliable rubber surrounding the not-sponges to form an airtight seal that keeps the ink drying out. The tube going into the black ink assembly on the right is much longer, snaking up to the top of the assembly before coming back down. Tube for the color ink has a shorter more direct path, and also mostly translucent with only a few blotches visible. The black ink tube looks dark. From here I can’t tell if the tube is dark because it is made of a different material, or if it’s dark because its innards are covered with black ink.

If its insides are covered with ink, that would imply a porous material in the print head rest position and these tubes deliver some amount of vacuum. Sucking ink into these tubes for whatever maintenance purpose it might serve. Do these tubes lead to a reservoir? Is there a limit to their ink sucking capacity? I shall seek answers to these questions later. Right now I will hold off disassembling this ink maintenance station. It might be more useful intact as reference while I explore whatever those tubes are connected to. And it would definitely be a huge mess to disconnect ink-filled tubes, so I’ll procrastinate on that and do something else instead.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here to rewind back to where this adventure started.