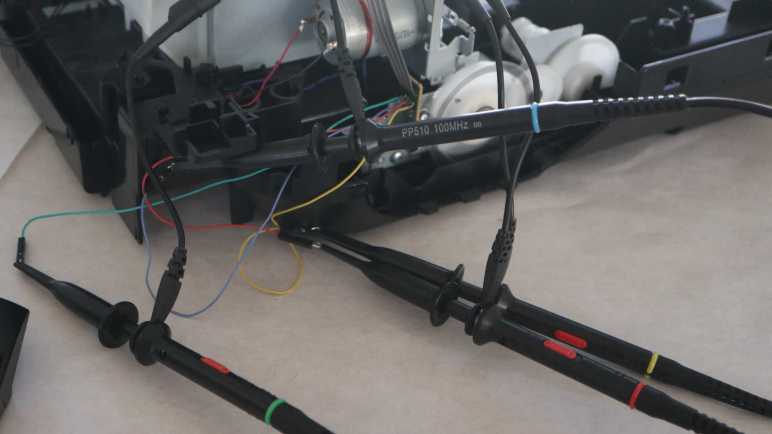

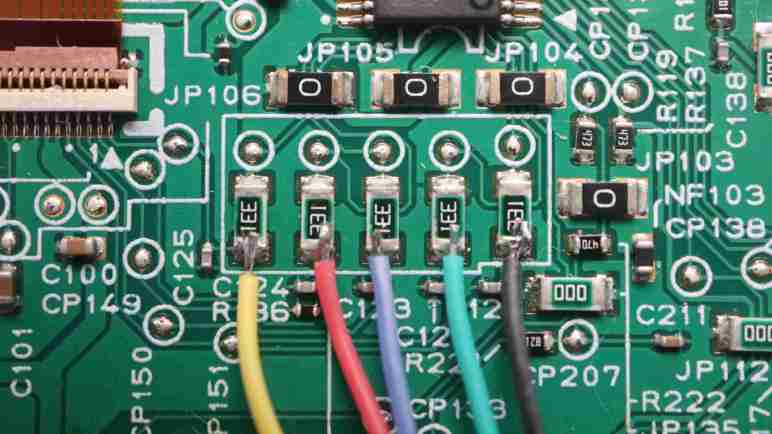

I’ve got an Arduino Nano connected to the internals of a Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet, specifically the quadrature encoder reporting on rotational motion of the paper feed motor gear assembly. After capturing the power-up sequence, I pressed the button again to capture the power-down standby sequence.

This standby sequence took twice as long as the power-up sequence, 18 seconds versus 9. Almost 11 seconds were spent rolling backwards relative to printing feed direction, traversing about 248,000 encoder counts. Eight times more than the backwards roll during power-up, which traversed ~31,000 encoder counts. That long rearward roll was followed by a forward roll for ~25,000 encoder counts.

During this roll, there were no paper motion and the print carriage sits in the parked position. What effect could this roll have? At the moment, my only guess is something preparing the ink cartridges to sit for a while. It would make sense for the power-up sequence to prepare the ink cartridges for use, and then for the standby sequence to prepare them for storage. Trying to figure out the details of this preparatory work is on the to-do list for later this teardown.

Besides that very long motion, there are several small movements back and forth. Looking at the data, I can see the times and duration differ between them, but each of those smaller movements traversed 1800 encoder counts. Reviewing the startup sequence, most of those small movements were also 1800 encoder counts. This is interesting. I will have to determine how many degrees of rotation corresponds to 1800 encoder counts, then look for a mechanism that corresponds to such a rotation during later disassembly. This little detail should be easier to understand than the actual printing process.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here to rewind back to where this adventure started.

Captured CSV and Excel worksheets are included in the companion GitHub repository.