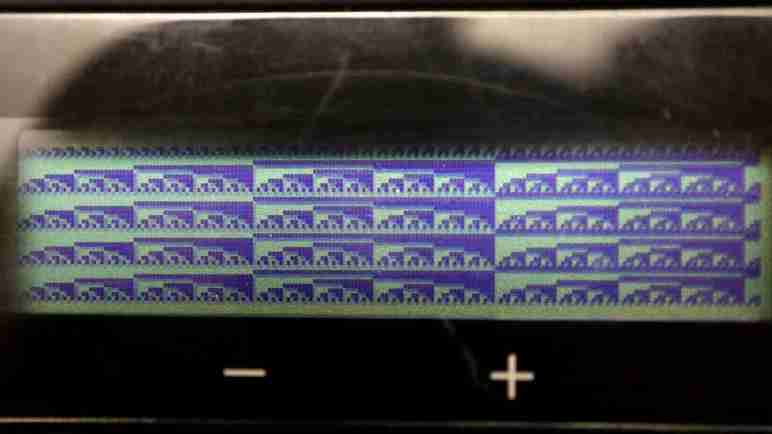

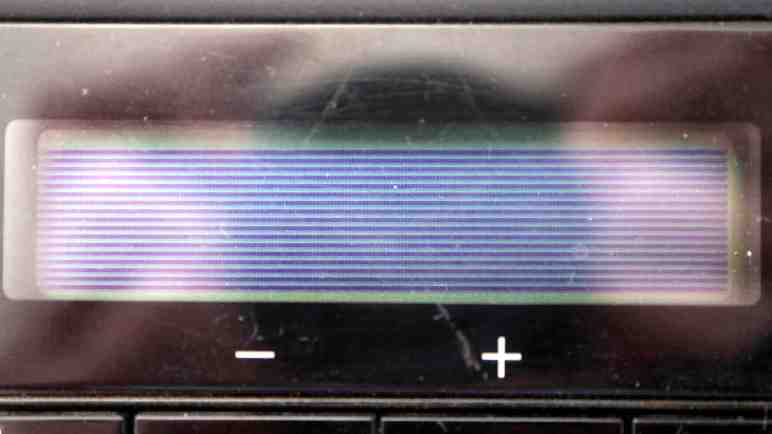

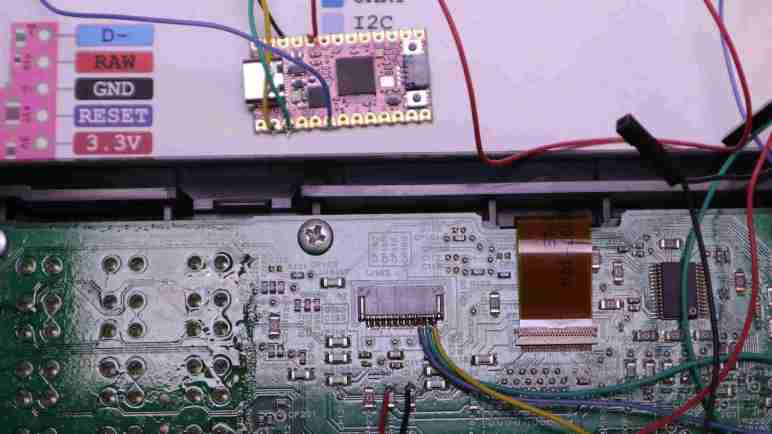

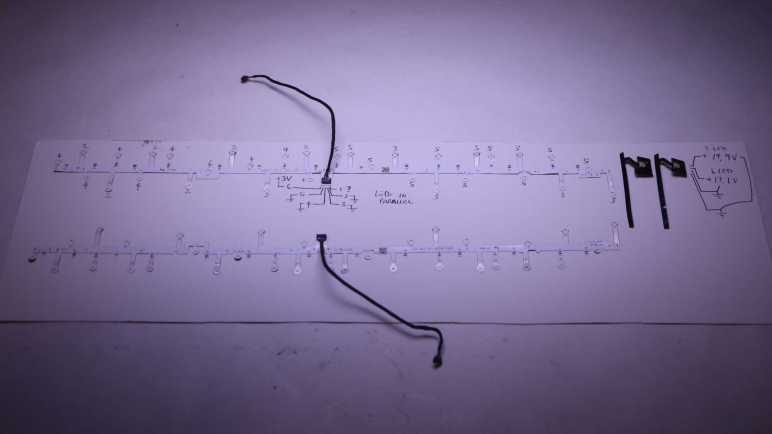

After a small (if not necessarily elegant) enhancement to adafruit_framebuf class, I can use it for basic graphical operations on the bit-mapped LCD of a salvaged Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet control panel. I then set my sights on adapting it to work with Adafruit’s graphics compositing engine displayio, but that turned out to be more difficult than I had thought.

I don’t know the full history but looking in hindsight I think displayio was optimized for sprite rendering, the most performance-critical part of a 2D game engine. Such a system would support products like Adafruit PyGamer. Not so important for this inkjet control panel LCD, whose refresh rate tops out at just under 14 frames per second. But I thought it would be fun anyway.

Adafruit has displayio drivers for their most popular screens and obviously my LCD is none of them. Looking for an appropriate tool, I found their framebufferio class which takes a frame buffer and returns a display object. Its target usage scenario allows using displayio with a RGB LED matrix, which has resolutions with similar order of magnitude as my LCD. This looks promising.

When I fed framebufferio my FrameBuffer class, I crashed my KB2040 which restarted in safe mode. (Indicated by triple blinking yellow LED.) Annoyingly, when a CircuitPython device crashes and reboots like this, Mu closes its serial terminal so I couldn’t read the error message before it immediately disappeared. I had to bring in a different serial monitor tool in order to see the error:

TypeError: 'FrameBuffer' object does not support 'protocol_framebuffer'Darn. Looks like the CircuitPython frame buffer object I had been working on, isn’t the CircuitPython frame buffer object expected by framebufferio. If I want this to work, I have to implement “protocol_framebuffer“, but what is it? Clicking on the link brought me to something called circuitpython_typing.FrameBuffer, which forwards to rgbmatrix.RGBMatrix. I added methods to my FrameBuffer-derived class in order to match those listed for RGBMatrix, but that was not good enough.

Digging deeper meant going into core CircuitPython written in C. I found framebufferio/FrameBufferDisplay.c which had this line:

self->framebuffer_protocol = mp_proto_get_or_throw(MP_QSTR_protocol_framebuffer, framebuffer);I think this is where my error message came from, so the next step is to find more information on the expected protocol which was declared in the associated header file FrameBufferDisplay.h.

typedef struct _framebuffer_p_t {

MP_PROTOCOL_HEAD // MP_QSTR_protocol_framebuffer

// Mandatory

framebuffer_get_bufinfo_fun get_bufinfo;

framebuffer_swapbuffers_fun swapbuffers;

framebuffer_deinit_fun deinit;

framebuffer_get_width_fun get_width;

framebuffer_get_height_fun get_height;

// Optional getters

framebuffer_get_bytes_per_cell_fun get_bytes_per_cell; // default: 2

framebuffer_get_color_depth_fun get_color_depth; // default: 16

framebuffer_get_first_pixel_offset_fun get_first_pixel_offset; // default: 0

framebuffer_get_grayscale_fun get_grayscale; // default: grayscale if depth < 8

framebuffer_get_native_frames_per_second_fun get_native_frames_per_second; // default: 60

framebuffer_get_pixels_in_byte_share_row_fun get_pixels_in_byte_share_row; // default: false

framebuffer_get_reverse_pixels_in_byte_fun get_reverse_pixels_in_byte; // default: false

framebuffer_get_reverse_pixels_in_word_fun get_reverse_pixels_in_word; // default: false

framebuffer_get_row_stride_fun get_row_stride; // default: 0 (no extra row padding)

// Optional -- default is no brightness control

framebuffer_get_brightness_fun get_brightness;

framebuffer_set_brightness_fun set_brightness;

} framebuffer_p_t;This is beyond my current understanding of CircuitPython code. Does it mean framebufferio only works with Adafruit’s own frame buffer objects written in C? Or is this compatible with user-created Python code somehow? Again I tried modifying my FrameBuffer-derived class to fit this signature, but either I made a mistake somewhere or it is fundamentally impossible. I wish I could get finer-grained error message telling me where exactly I failed to support protocol_framebuffer, but I just keep getting the same failure leaving me stabbing in the dark.

After a few hours of fiddling without success, I abandoned displayio compatibility and wrote up this page in case my future self wants to pick up where I left off today. Without displayio I’ll learn what I can from using adafruit_framebuf. First lesson: updating LCD at a high frame rate required task synchronization.