I knew web development frameworks like Angular proclaim to offer a full package, but it’s always enlightening to find out what “full” does and doesn’t mean in each context. I had expected Angular to have its own layout engine and was mildly surprised (but also delighted) to learn the official recommendation is to use standard CSS, migrating off Angular-specific interim solutions.

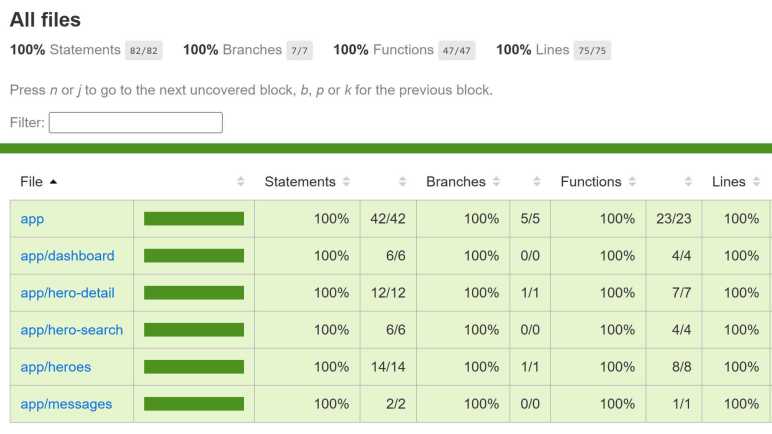

Another area I knew Angular offered is a packaged set of testing tools: a combination of generic JavaScript testing tools and Angular-specific components already set up to work together as a part of Angular application boilerplate. We can kick off a test pass by running “ng test” and when I did so, I saw the following error message:

✔ Browser application bundle generation complete.

28 02 2023 09:17:22.259:WARN [karma]: No captured browser, open http://localhost:9876/

28 02 2023 09:17:22.271:INFO [karma-server]: Karma v6.4.1 server started at http://localhost:9876/

28 02 2023 09:17:22.272:INFO [launcher]: Launching browsers Chrome with concurrency unlimited

28 02 2023 09:17:22.277:INFO [launcher]: Starting browser Chrome

28 02 2023 09:17:22.279:ERROR [launcher]: No binary for Chrome browser on your platform.

Please, set "CHROME_BIN" env variable.

Test runner Karma looked for Chrome browser and didn’t find it. This is because I’m running my Angular development environment inside a VSCode Dev Container, and this isolated environment couldn’t access the Chrome browser on my Windows 11 development desktop. It needs its own installation of Chrome browser and be configured to run in headless mode. (Which is itself undergoing an update but that’s not important right now.)

From these directions I installed Chrome in the container via command line.

sudo apt update

wget https://dl.google.com/linux/direct/google-chrome-stable_current_amd64.deb

sudo apt install ./google-chrome-stable_current_amd64.deb

Then Karma needs to be configured to run Chrome in headless mode. However, default Angular app boilerplate did not include karma.conf.js file which we need to edit. We need to tell Angular to create one:

ng generate config karma

Now we can edit the newly created file karma.conf.js following directions from here. Inside the call to config.set(), we need to define a custom launcher called “ChromeHeadless” then use that launcher in the browsers array. The results will look something like the following:

module.exports = function (config) {

config.set({

customLaunchers: {

ChromeHeadless: {

base: 'Chrome',

flags: [

'--no-sandbox',

'--disable-gpu',

'--headless',

'--remote-debugging-port=9222'

]

}

},

basePath: '',

frameworks: ['jasmine', '@angular-devkit/build-angular'],

plugins: [

@@ -33,7 +44,7 @@ module.exports = function (config) {

]

},

reporters: ['progress', 'kjhtml'],

browsers: ['ChromeHeadless'],

restartOnFileChange: true

});

};

With these changes I can run “ng test” inside my dev container without any errors about running Chrome browser. Now I have an entirely different set of errors about object creation!

Appendix: Error Messages

Here are error messages I saw during this process, in order to help people to find these instructions by searching for the error message they saw.

Immediately after installing Chrome, running “ng test” will try launching Chrome but not in headless mode which will show these errors:

✔ Browser application bundle generation complete.

28 02 2023 17:50:43.190:WARN [karma]: No captured browser, open http://localhost:9876/

28 02 2023 17:50:43.202:INFO [karma-server]: Karma v6.4.1 server started at http://localhost:9876/

28 02 2023 17:50:43.202:INFO [launcher]: Launching browsers Chrome with concurrency unlimited

28 02 2023 17:50:43.205:INFO [launcher]: Starting browser Chrome

28 02 2023 17:50:43.271:ERROR [launcher]: Cannot start Chrome

Failed to move to new namespace: PID namespaces supported, Network namespace supported, but failed: errno = Operation not permitted

[0228/175043.258978:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq: No such file or directory (2)

[0228/175043.259031:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_max_freq: No such file or directory (2)

28 02 2023 17:50:43.271:ERROR [launcher]: Chrome stdout:

28 02 2023 17:50:43.272:ERROR [launcher]: Chrome stderr: Failed to move to new namespace: PID namespaces supported, Network namespace supported,

but failed: errno = Operation not permitted [0228/175043.258978:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq: No such file or directory (2)

[0228/175043.259031:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_max_freq: No such file or directory (2)

This has nothing to do with Karma because if I run Chrome directly from the command line, I see the same errors:

$ google-chrome

Failed to move to new namespace: PID namespaces supported, Network namespace supported, but failed: errno = Operation not permitted

[0228/175538.625191:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq: No such file or directory (2)

[0228/175538.625244:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_max_freq: No such file or directory (2)

Trace/breakpoint trap

Running Chrome with just the “headless” flag is not enough.

$ google-chrome --headless

Failed to move to new namespace: PID namespaces supported, Network namespace supported, but failed: errno = Operation not permitted

[0228/175545.785551:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq: No such file or directory (2)

[0228/175545.785607:ERROR:file_io_posix.cc(144)] open /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_max_freq: No such file or directory (2)

[0228/175545.787163:ERROR:directory_reader_posix.cc(42)] opendir /tmp/Crashpad/attachments/9114d20a-6c9e-451e-be47-353fb54f28be: No such file or

directory (2) Trace/breakpoint trap

We have to disable sandbox to get further, though that’s not the full solution yet either.

$ google-chrome --headless --no-sandbox

[0228/175551.357814:ERROR:bus.cc(399)] Failed to connect to the bus: Failed to connect to socket /run/dbus/system_bus_socket: No such file or dir

ectory [0228/175551.361002:ERROR:bus.cc(399)] Failed to connect to the bus: Failed to connect to socket /run/dbus/system_bus_socket: No such file or dir

ectory [0228/175551.361035:ERROR:bus.cc(399)] Failed to connect to the bus: Failed to connect to socket /run/dbus/system_bus_socket: No such file or dir

ectory [0228/175551.365695:WARNING:bluez_dbus_manager.cc(247)] Floss manager not present, cannot set Floss enable/disable.

We also have to disable the GPU. Once done as per Karma configuration above, things will finally run inside a Dev Container.