I want to use a MP1584 buck converter module for a solar-powered project, and to explore its behavior I used a bench power supply to vary volage input from zero volts up to expected operating voltage. I heard an audible screech from the circuit within the 3-5 volt range and decided not to go further until I better understood what’s going on.

The first step to problem solving is always to Read The Fine Manual, in this case MP1584 data sheet published by Monolithic Power Systems. The first surprise was the big read “NOT RECOMMENDED FOR NEW DESIGNS REFER TO MP2338” stamped across every page. I guess this chip is getting phased out by Monolithic, and at some point I will have to learn about a different chip. But that doesn’t matter today so I proceeded to read about its startup behavior. Specifically the EN (Enable) pin on this chip. According to this document, MP1584 will start up when EN is above 1.5V.

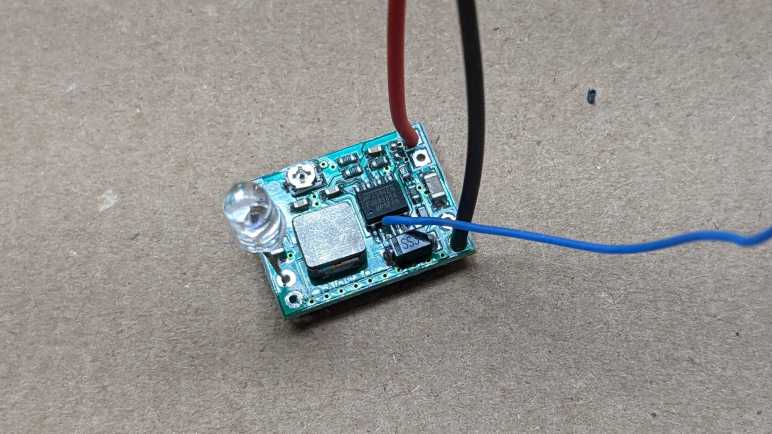

Great, what does that mean for my little board, purchased from Amazon from the lowest bidder that day? I laid the board flat and started probing. From what I can tell, the EN pin is connected to a straightforward voltage divider ladder, using two resistors of equal value. These little surface mount resistors have “104” printed on them, indicating they are 100kΩ plus or minus some percentage of tolerance.

Here is the same image in light grayscale, and I filled some color into the relevant areas.

EN trace is in blue, and its circuit board trace immediately goes under the chip to emerge to the left moving up. Running between the two poles of a capacitor(?) it reaches the two voltage dividing resistors. The top resistor bridges between EN and ground, which I filled in black. The lower resistor bridges between EN and voltage input, which I filled in red. Vin can be seen connecting to the Vin solder pads to the upper right.

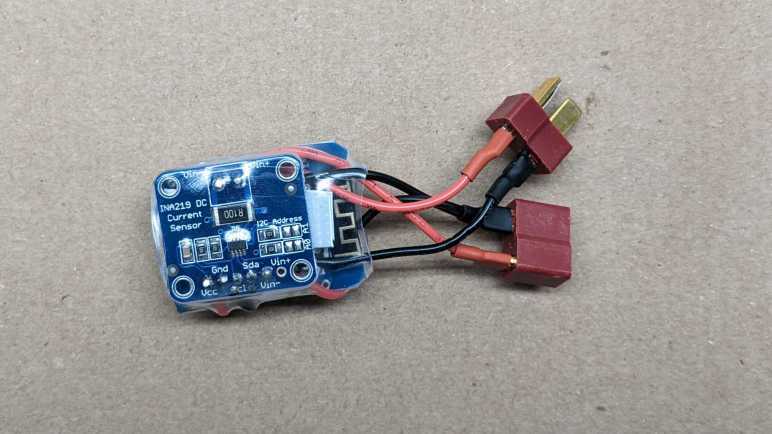

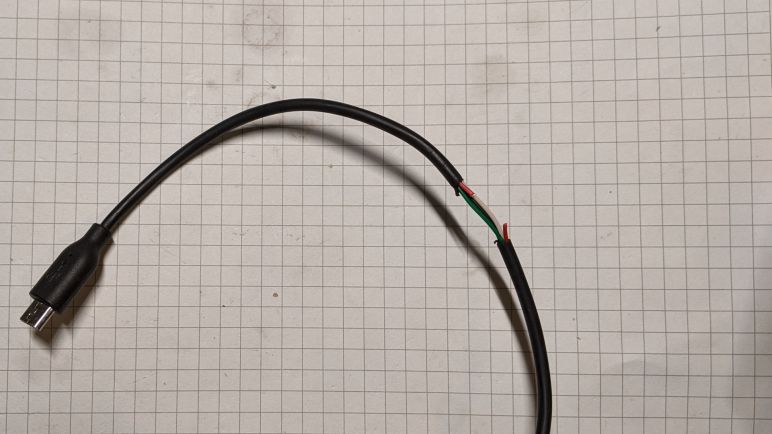

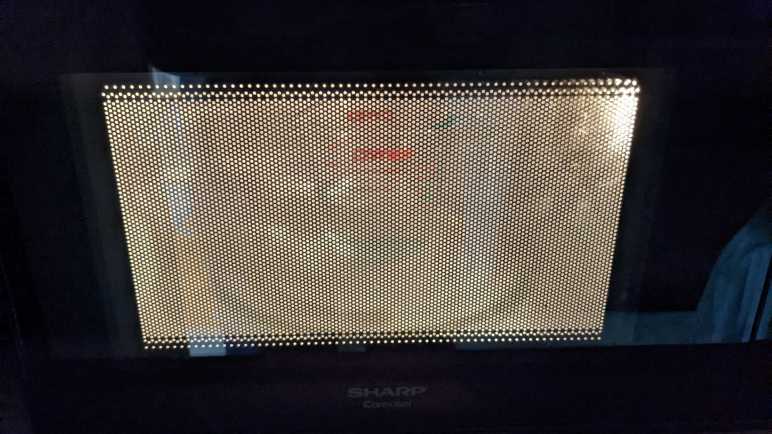

A voltage divider with two equal value resistors means voltage of EN will be half of input voltage. To test this hypothesis, I soldered a wire to this pin so I could measure its voltage as I vary the input voltage. A small 5mm LED module was connected to MP1584 output. This is a self-cycling unit that quickly flashes through different colors from RGB mixes.(*) I used it here because it tolerates a slightly wider range of input voltage and current than just a single diode, plus it is inexpensive and disposable in case something went wrong with this experiment.

Clipping a voltage meter to the blue wire, I quickly confirmed the hypothesis is correct. EN voltage is approximately half of input. Therefore, if a MP1584 activates at 1.5V, this circuit will activate with 3V input. This is a problem when the potentiometer has been adjusted for 3.3V output. This is a buck converter. It lowers voltage and could not raise it! No wonder it was unhappy and screeched its displeasure.

But now that I have a basic understanding of how this module decides to come alive, I could modify it to suit the project at hand.