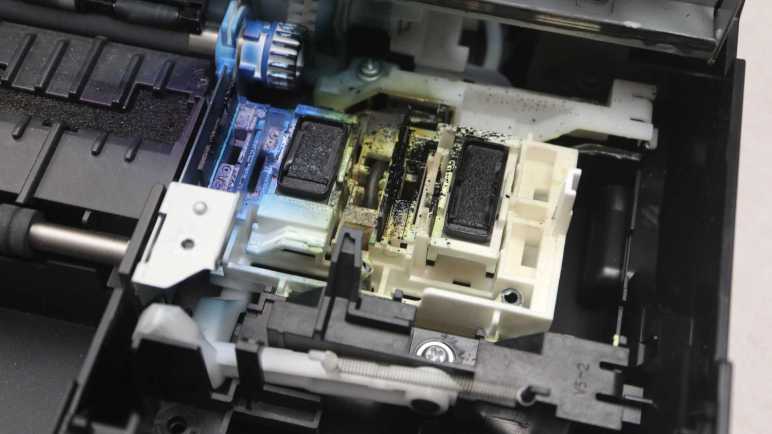

I’ve been playing with the print head carriage mechanism of a Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet, manually sliding it back and forth. I found no driveshafts conveying motor rotation, but I did find one lever it would push when at a specific position. The carriage also manipulates an ink-splattered assembly that I believe to be responsible for keeping the print heads in good working order.

The carriage pushes the maintenance assembly via its vertical tab on the far right, the only portion high enough to directly touch the carriage.

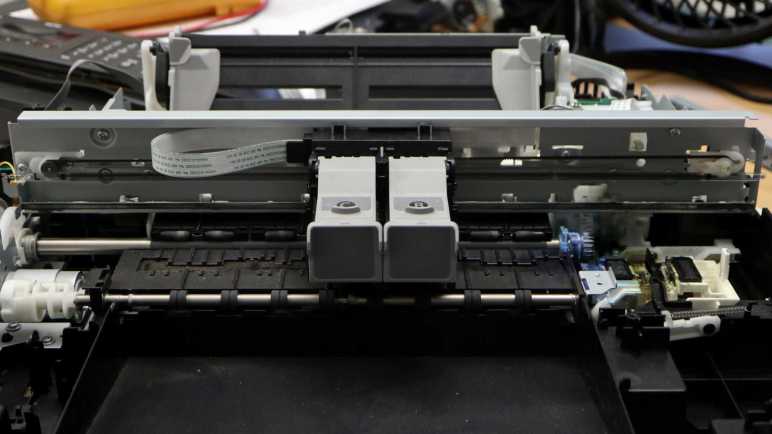

When the print carriage is absent, a spring pulls this assembly down and to the left. Here it is in the retracted position.

It can slide up and to the right at a ~45 degree angle for approximately 1cm. A small tab (circled in red) held back a section corresponding to the color ink cartridge so it is not raised as high as the rest of the assembly.

Beyond this point, the assembly only sides to the right with no further vertical movement. During this motion, the color ink cartridge subsection is allowed to rise up to join the rest. This right-most position, where the assembly is at its highest, corresponds to the print carriage parked standby position.

The two dark rectangles probably help keep the ink from drying out between print sessions. To the left of each of those two rectangles is a corresponding wiper blade. But if this assembly always moves in sync with the print head, there would be no wiping action.

Wiping is made possible by a spring-loaded latch. Here’s the maintenance assembly again in its highest right-most parked position as shown above, but at a different camera angle. The spring in the center of this picture pulls the assembly down and to the left.

As the print carriage moves left, the assembly is pulled left. It barely got past the 45-degree down-and-left transition before the latch (circled in red) blocked further movement. This blockage keeps this maintenance assembly in place while the print carriage continues moving left, and this difference in motion lets the wipers work.

The top of the latch reaches up towards the print carriage, high enough to be engaged by a tab on the carriage between the two ink cartridge slots. Ink cartridges were removed from this picture for a better view.

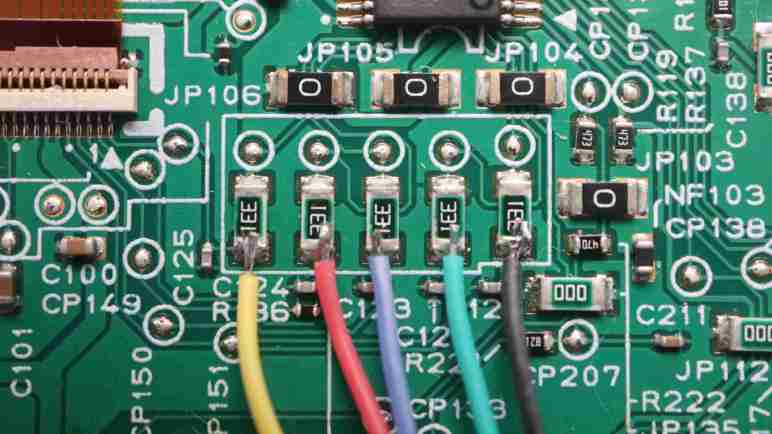

Once the wiping action is complete, the carriage moves further left and pushes the latch down.

This allows the maintenance assembly to slide the rest of the way down, retracting the two wipers away from their corresponding print heads.

Now that I have knowledge of how this assembly moves, I’ll take a closer look at its components.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here to rewind back to where this adventure started.