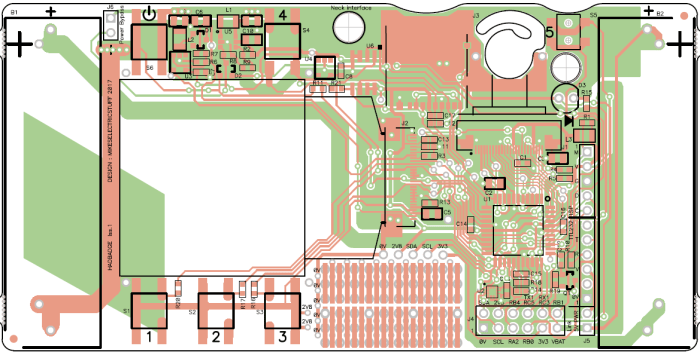

A review of the Hackaday Superconference 2017 “camera badge” hardware provided adequate orientation but no lightning strike of project inspiration. Today I did find the project page for last year’s Supercon badge as well as a summary page of some things people have created with the 2016 badge. People have done some really cool things with that badge serving as foundation. I’m feeling intimidated but also determined to keep trying to see what I can devise.

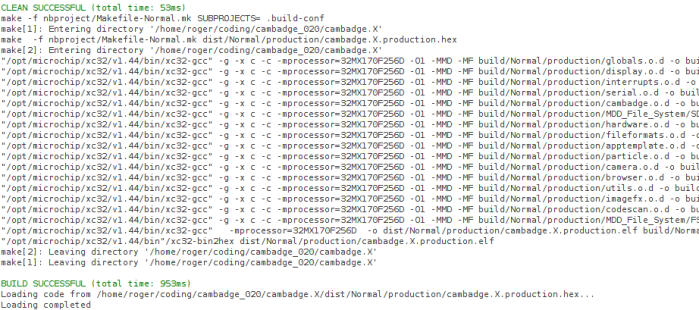

Today’s tactic: Dive into the data sheet for the Microchip control unit at the heart of the 2017 badge, the PIC32MX170F256D. No matter what else happens, it would be good to have an overview of what the chip can and can’t do. I was also hoping that a review of the data sheet will unveil something about the chip that would inspire a project. Since I’ve already read the PIC16F18345 data sheet back-to-back, I hoped the familiarity with Microchip conventions will give me a head start.

The first surprise was the size (length) of the data sheet. Only 344 pages when the much simpler PIC16F18345 chip had a 491 page document. It didn’t take long for me to figure out why, since every feature section started the same way: a disclaimer that the data sheet was only the summary and tells me I need to do more reading if I want the details.

Well, that explains the size! For my purposes today, it’s no big deal. In fact it is helpful since the summaries mean I don’t have to press “Page Down” as often.

There are some comfortable commonality with the PIC16F18345 I’m familiar with: Timers and comparators. Digital I/O and analog input (ADC.) Communication via SPI, I2C, UART. And all these peripheral modules are mapped into a memory space so everything is accessed via memory reads and writes. And finally: a big focus on power management.

There are some differences that I might miss in the PIC32MX1XX:

- PWM seems to have gone missing, unless there is a much more advanced component that can serve similar purposes but I don’t recognize it as such.

- I/O pins are much less powerful. The PIC16F can handle up to 50mA on any single I/O pin and up to 250mA total. The PIC32MX can only handle 15mA per pin with 200mA total.

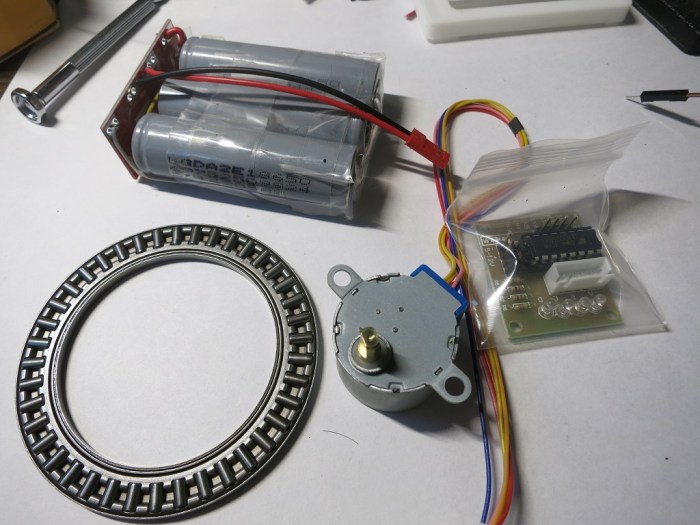

- Narrower voltage range: Unlike the super flexible and relaxed PIC16F that is happy to run with anything from 2.3V to 5.5V, the PIC32MX prefers to stay within 2.3V to 3.6V. The maximum is listed as 4.0V, so it might be dicey to run this thing on a single rechargeable lithium cell – the nominal voltage is 3.7V but a fully charged cell might be up to 4.2V.

The PIC32MX uses a different instruction set (MIPS32 M4K) and that’s no surprise. I expect to be mostly isolated from this fact by writing in C and letting the XC compiler worry about the instruction set. The PIC32MX also requires more support circuitry. Whereas the PIC16F can literally connect directly to a battery and it’ll start running. Again I’m mostly isolated in this case because the camera badge is already built for me and all the support components are already on board.

And now, on to the things that might be interesting. I started with the title description: “32-bit Microcontrollers (up to 256 KB Flash and 64 KB SRAM) with Audio and Graphics Interfaces, USB, and Advanced Analog”

The first thing to catch my eye: USB, backed by this promising-sounding bullet point on the cover page: “USB 2.0-compliant Full-speed OTG controller“. USB OTG would let us plug-in USB peripherals and greatly expand the possibilities of what we can do. Alas, my hopes were dashed when page 2 clarified that USB OTG is only on the PIC32MX2XX series and absent on the PIC32MX1XX we have on the camera badge. So that’s out.

The “Advanced Analog Features” bullet items seem to mostly center around support for capacitive touch sensing, mostly around their “mTouch” design. Since their reference implementation involves copper traces and plates on a printed circuit board, that won’t be directly applicable to me. But perhaps this type of support circuitry can be hacked into something fun.

I have yet to explore the world of audio electronics, so sadly the audio interface features are mostly gibberish to me. I had higher hopes for the “Graphics Interfaces” side of that claim and… I came up empty-handed. There’s nothing that obviously said “graphics” to me on the feature set. The closest thing I can find is the PMP (Parallel Master Port) peripheral which is good for talking to display panels, and is indeed already employed on the camera badge to drive the 128×128 OLED screen.

So in the category of “stuff that the chip can do, but isn’t already being used” the best candidate at the moment is the analog circuitry to support capacitive touch. Since I don’t have time for a OSH Park PCB, it’ll have to be something creative. Perhaps something as primitive as taping down loops of wire to cardboard or 3D-printed plastic parts.

The gears in the brain keep churning…