I want to repurpose a malfunctioning monitor as a lighting fixture. I was tempted to separate the LED backlight from the LCD module, because that LED illumination is the functionality I actually cared about. But I might need the LCD portion for further diagnostics, so I held off separation for now. Either way, I need an ESP32 generating VGA signal of full screen white to keep the monitor from going into sleep mode. Dangling it outside the monitor is functional, but not very elegant. There’s plenty of space inside the monitor enclosure for a little ESP32 development board, I just have to find places to solder the necessary wires.

The signal output side is easy because we know where the VGA input port is. There was no exposed metal to solder on the top side, but it is a through-hole part so soldered pins are accessible from the bottom. A multimeter set to continuity detection mode quickly found the five critical signal pins I need to solder to: red, green, blue, horizontal sync, and vertical sync.

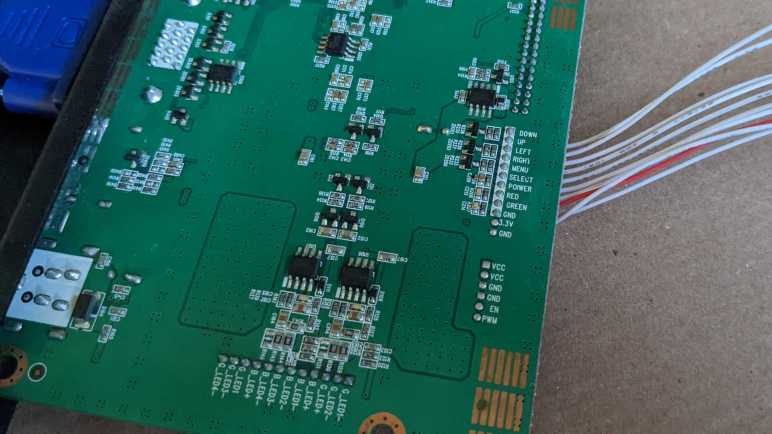

I also probed the VGA ground pins and found them to be common to electrical ground throughout the entire board, so that would be easy. The only remaining challenge was to find an appropriate power source for the ESP32. I found the power supply input jack, but that comes in at 24V DC and too high for the ESP32’s onboard voltage regulator. I didn’t want to add a buck converter to the circuit because I’m sure something already existed on this board. The answer was found on the connector for physical control buttons for this monitor. We see a row of wires each corresponding to a button: Down, Up, Left, Right, Menu, Select, Power. Below that are wires for the two status LEDs: red and green. And finally, GND and 3.3V, which I could tap to power my ESP32.

With these wires soldered in place, the ESP32 will have power as soon as the monitor is plugged in, eliminating the need for a separate power supply. It will generate a VGA signal sent directly to the VGA input port, eliminating the need for a separate VGA cable. When the power button is pressed, the monitor will wake up and detect a valid VGA signal and display full screen white, turning the monitor (and its useless sub pixels) into a lighting fixture.

Small black heat-shrink tubing helped me keep the wires organized, and a large clear heat-shrink tube encased the ESP32 board providing electrical insulation from the monitor enclosure. A small piece of double-sided tape holds the entire assembly inside the monitor. It lives here now. This lets me test the concept and verify the system could run long term in this state. If proven successful, I will return and separate the LED backlight to unlock full brightness.