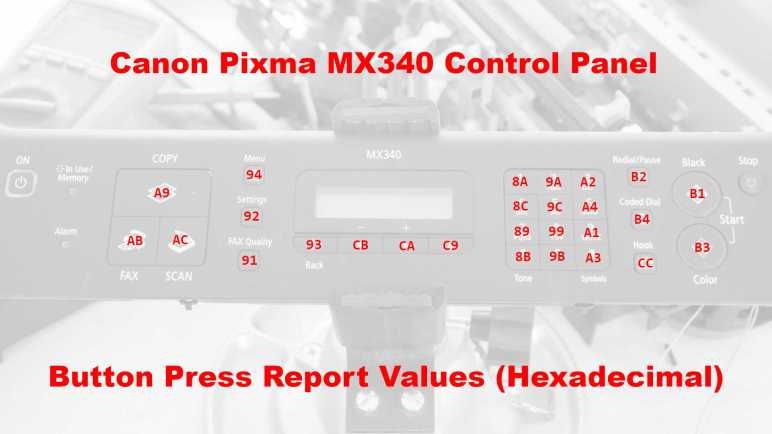

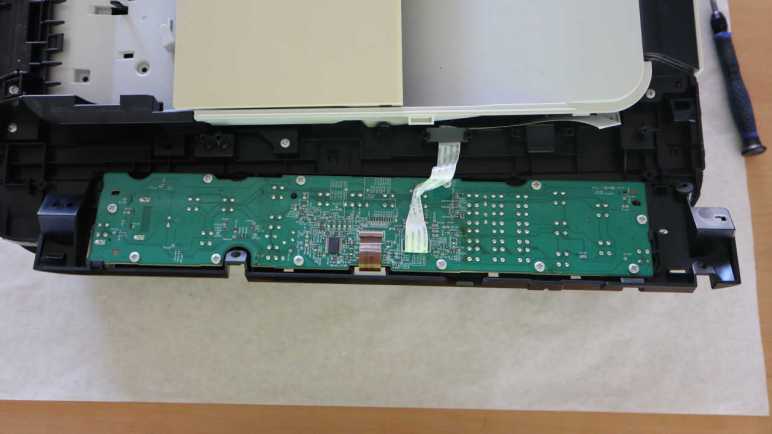

A rudimentary Python program helped me get the button matrix status report scan code sent by the control panel of a Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet. While I was on the machine smashing buttons, I also figured out how to toggle the state of two LEDs (“In Use/Memory” and “WiFi”) under control of the same NEC K13988 chip. (The other two LEDs “Power” and “Alarm” have been traced to direct main board wires.)

This is new territory, because those two LEDs did not change during my initial six logic analyzer capture targets, so I had no information on commands to toggle their state. Now I can now add two more procedures for logic analyzer captures:

- Start a fax transmission. Since I don’t have a landline, it will hang until timeout error. Before that happens, though, “In Use/Memory” will blink. Approximately one second illuminated, half second dark, and repeat.

- In the device settings menu, it is possible to activate/inactivate the machine’s WiFi function. The WiFi LED status will update in response to user menu selection.

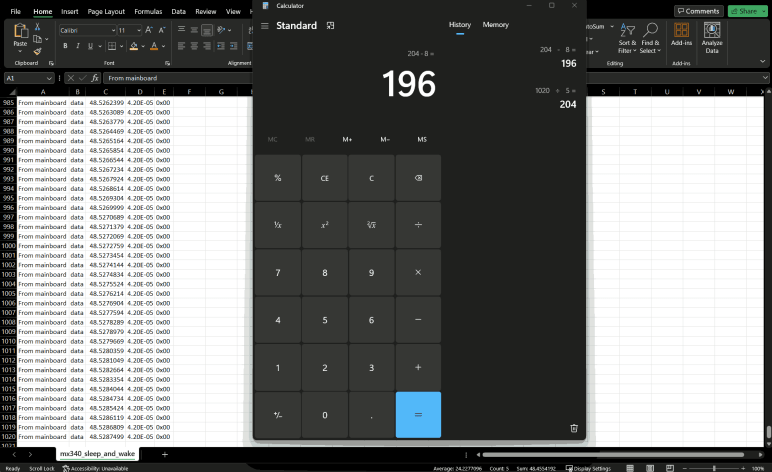

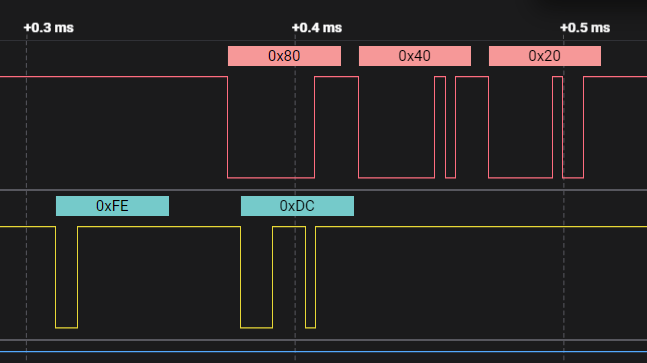

Now that I recognize the pattern for LCD screen updates, I could comb through the data looking for transmissions outside of that pattern. Maybe I should have waited to analyze this until I have updated my Python data filter program to exclude LCD screen updates for me, but I was impatient. As it turned out, it wasn’t very difficult to do it manually in Saleae Logic timeline view.

Since the “In Use/Memory” light can be set blinking without user interaction, that was easier to extract:

| Main board command | In Use/Memory LED |

|---|---|

| 0x0E 0xFB | ON |

| 0x0E 0xFF | OFF |

So far so good. I then repeated the exercise for WiFi LED which was more involved because the capture included several button keypresses and LCD screen updates I had to wade through.

| Main board command | WiFi LED |

|---|---|

| 0x0E 0xFF | ON |

| 0x0E 0xFD | OFF |

Hmm. 0x0E 0xFF is sent when I turned WiFi ON, and it’s also sent when In Use/Memory is OFF. At first I thought maybe I had been looking at the wrong bytes, but then I realized 0x0E is the command to update all LED state and the second byte is a parameter. In that earlier In Use/Memory table, WiFi LED was on. And in the above WiFi LED table, In Use/Memory was off. Those tables covered three out of four possible combinations, so I turned WiFi OFF and set In Use blinking and got 0x0E 0xF9 as the fourth value. Now I can plot the four possible commands in a table:

| In Use/Memory LED ON | In Use/Memory LED OFF | |

|---|---|---|

| WiFi LED ON | 0x0E 0xFB | 0x0E 0xFF |

| WiFi LED OFF | 0x0E 0xF9 | 0x0E 0xFD |

These four commands differ only in the final four bits. Here’s the same table, with those four bits in both hexadecimal and binary.

| In Use/Memory LED ON | In Use/Memory LED OFF | |

|---|---|---|

| WiFi LED ON | 0xB = 0b1011 | 0xF = 0b1111 |

| WiFi LED OFF | 0x9 = 0b1001 | 0xD = 0b1101 |

Now we can see the second least significant bit (bit mask 0b0010) dictates state of pin controlling WiFi LED state, and the third least significant bit (bit mask 0b0100) for In Use/Memory LED.

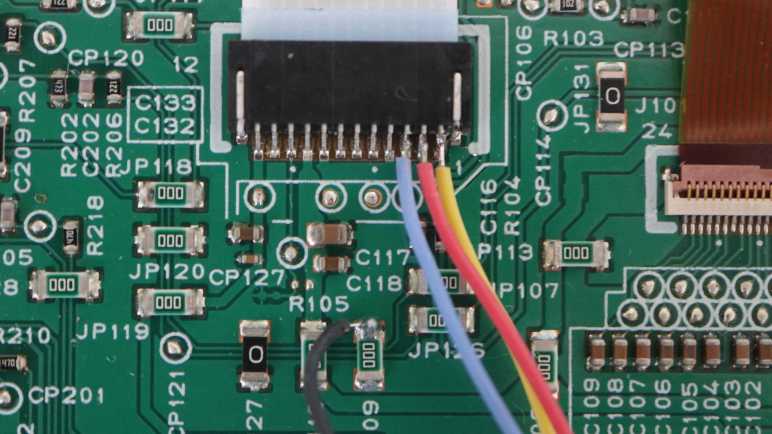

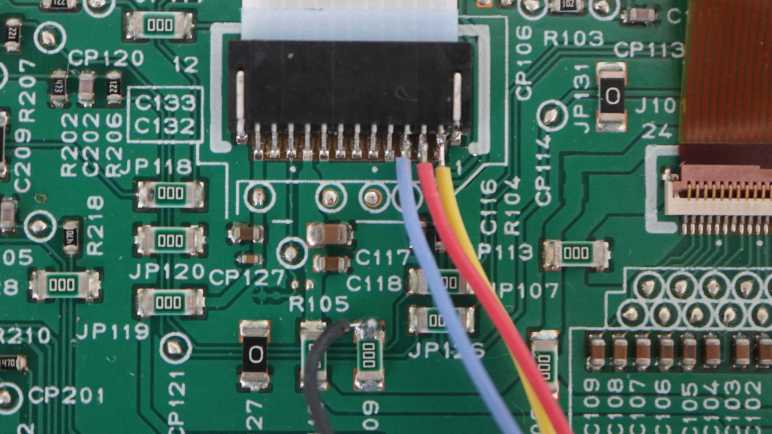

The mapping between bit value and LED on/off is reversed between these two because those pins are connected to different circuit components. In Use/Memory LED- is connected directly to K13988 pin 21, so setting that pin low illuminates the LED. In contrast, WiFi indicator is a higher power LED with its own 5.5VDC power feed, so the K13988 pin controls a transistor that grounds LED-. Setting that pin high activates the transistor and illuminates the WiFi LED.

Now that I know 0x0E is a command to control LED state, I reviewed the power-on sequence for 0x0E commands. It included parameters 0xFD and 0xFF listed above, but also 0xFC which turned off the least significant bit. I don’t know what that could be… I’ve traced through the circuit board and there isn’t anything else it could have connected to. Maybe that bit meant something in a different device, and Canon engineers carried over that code without realizing it? Whatever it might have been, it was quickly overwritten by 0x0E 0xFD roughly 250ms later, so it doesn’t matter much anyway.

Understanding the 0x0E commands for LED control filled in the last of my “known unknown” of MX340 internal serial communication. I tried to apply my lesson to my data filter program but stumbled out of the gate, tripped up by a USB serial adapter that was bad right out of the box.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here to rewind back to where this adventure started.