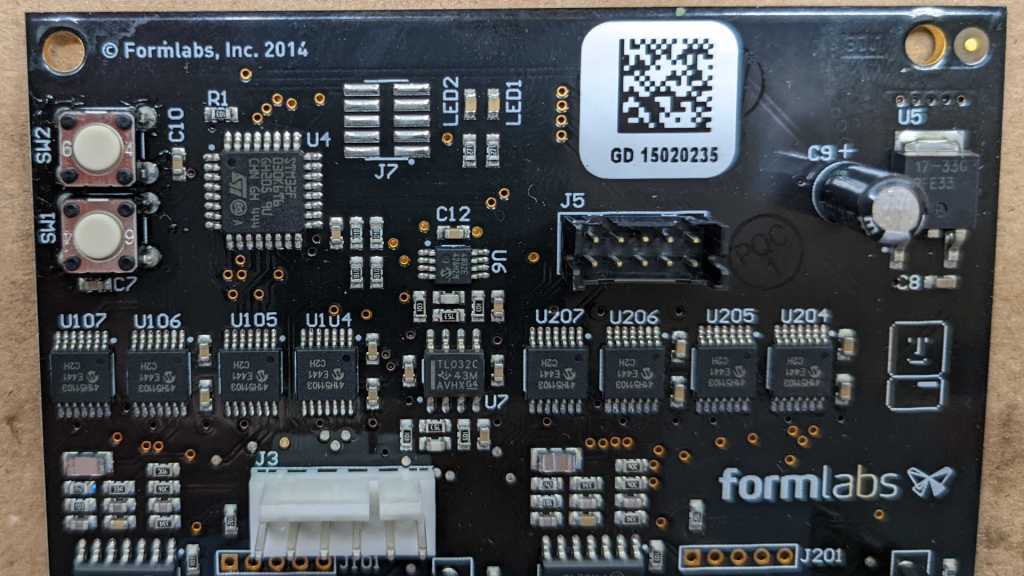

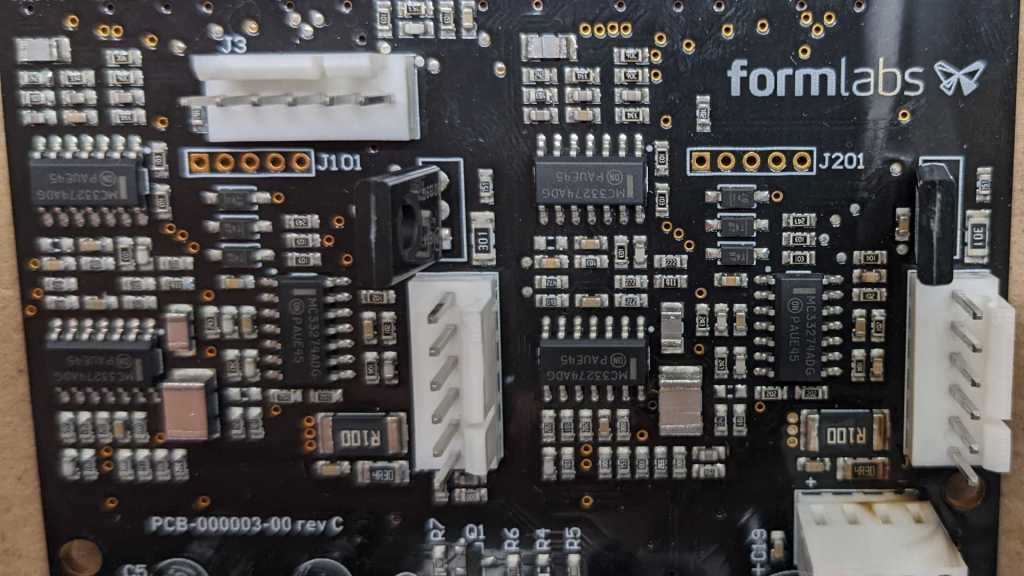

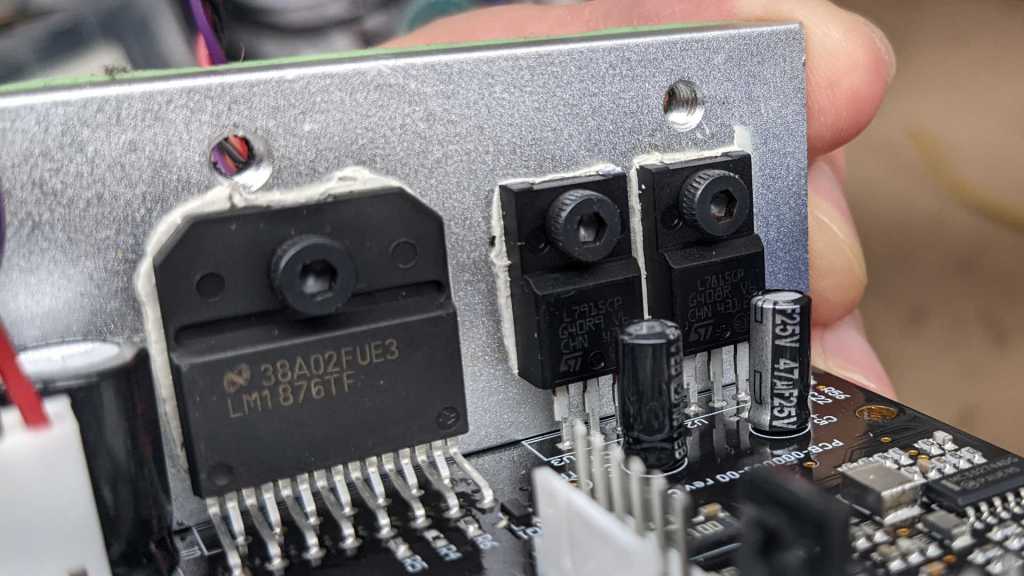

Thanks to Adafruit publishing an Arduino library for interfacing with SSD1305 display driver chip, I proved that it’s possible to control an OLED dot matrix display from a broken FormLabs Form 1+ laser resin 3D printer. But the process wasn’t seamless, I ran into several problems using this library:

- Failed to run on ESP32 Arduino Core due to watchdog timer reset.

- 4 pixel horizontal offset when set to 128×32 resolution.

- Sketch runs only once on Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense, immediately after uploading.

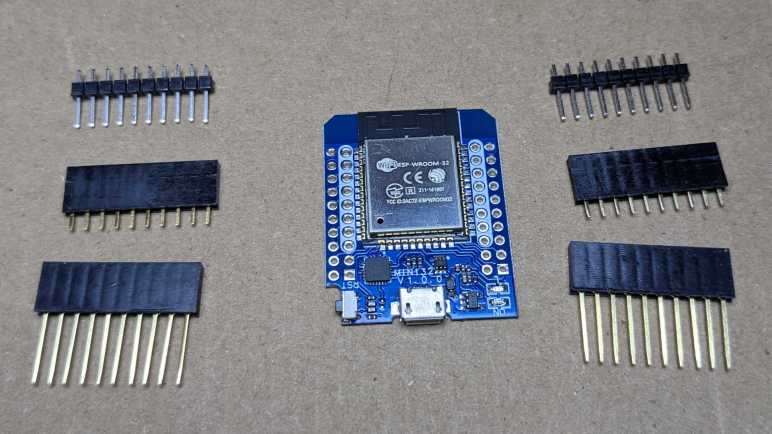

Since Adafruit published the source code for this library, I thought I’d take a look to see if anything might explain any of these problems. For the first problem of watchdog reset on ESP32, I found a comment block where the author notes potential problems with watchdog timers. It sounds like an ESP8266 is a platform known to work, so I should try that.

// ESP8266 needs a periodic yield() call to avoid watchdog reset.

// With the limited size of SSD1305 displays, and the fast bitrate

// being used (1 MHz or more), I think one yield() immediately before

// a screen write and one immediately after should cover it. But if

// not, if this becomes a problem, yields() might be added in the

// 32-byte transfer condition below.While I’m setting up an ESP8266, I could also try to address the horizontal offset. It seems a column offset of four pixels were deliberately added for 32-pixel tall displays, something not done for 64-pixel tall displays.

if (HEIGHT == 32) {

page_offset = 4;

column_offset = 4;

if (!oled_commandList(init_128x32, sizeof(init_128x32))) {

return false;

}

} else {

// 128x64 high

page_offset = 0;

if (!oled_commandList(init_128x64, sizeof(init_128x64))) {

return false;

}

}There was no comment to explain why this line of code was here. My best guess is the relevant Adafruit product has internally wired its columns with four pixels of offset, so this code makes a shift to compensate. If I remove this line of code and rebuild, my OLED displays correctly.

As for the final problem of running just once (immediately after upload) on an Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense, I don’t have any hypothesis. My ESP8266 happily restarted this test sketch whenever I pressed the reset button or power cycled the system. I’m going to chalk it up to a hardware-specific issue with the Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense board. At the moment I have no knowledge (and probably no equipment and definitely no motivation) for more in-depth debugging of its nRF52840 chip or Arm Mbed OS.

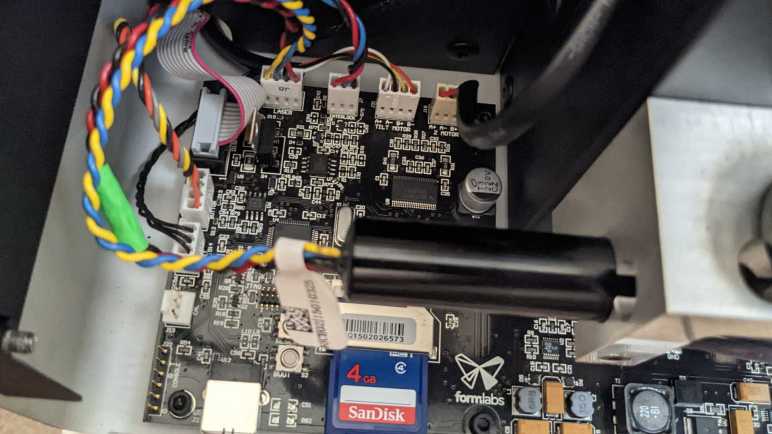

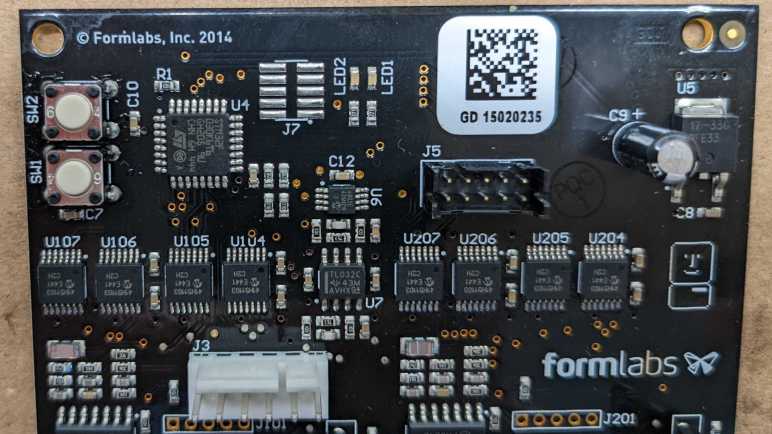

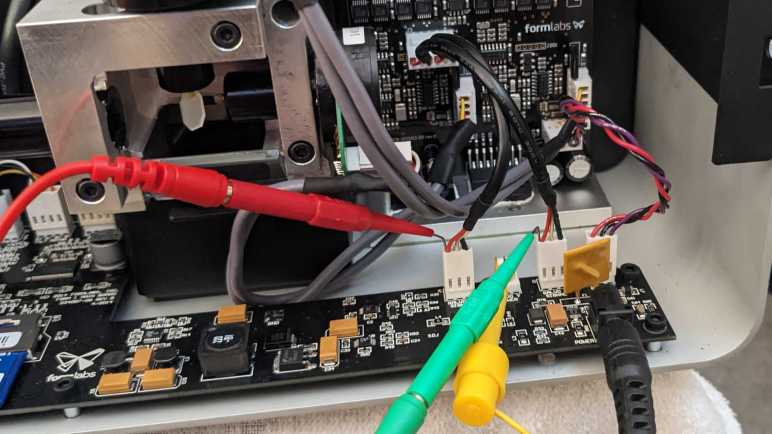

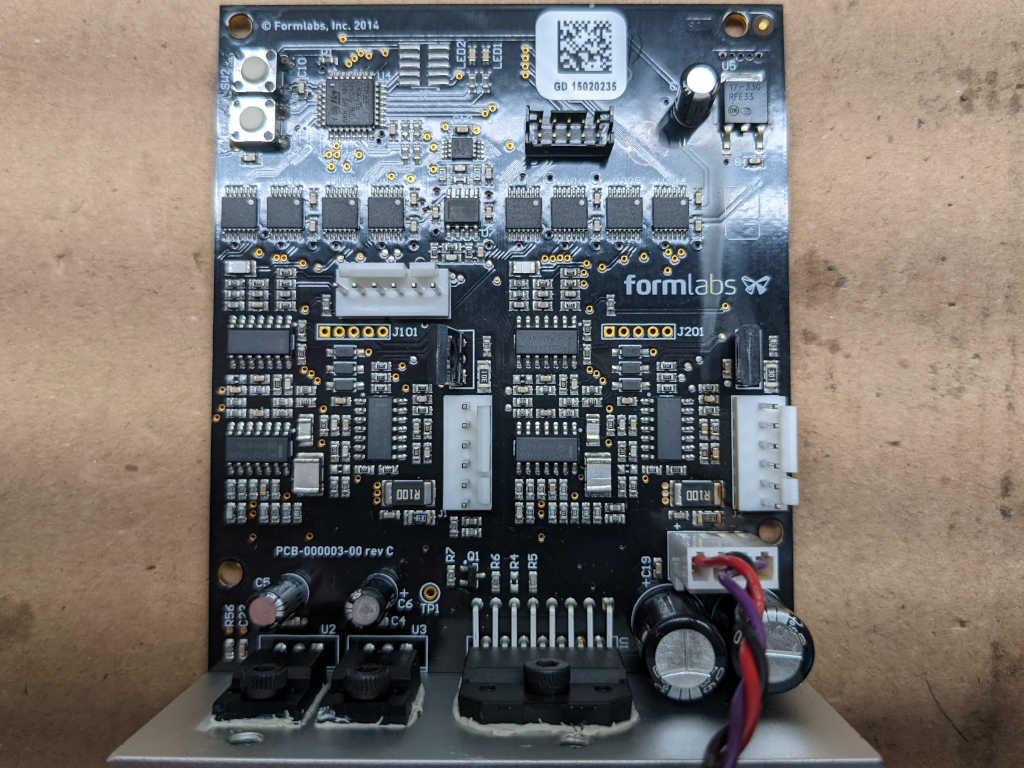

Now I have this OLED working well with an ESP8266, a hardware platform I have on hand, I can confidently describe this display module’s pinout.