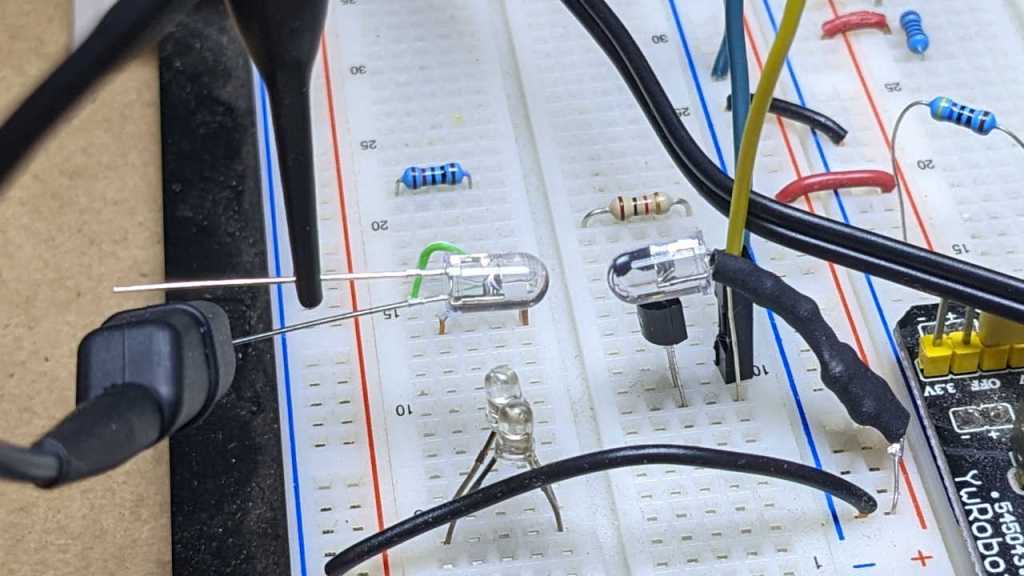

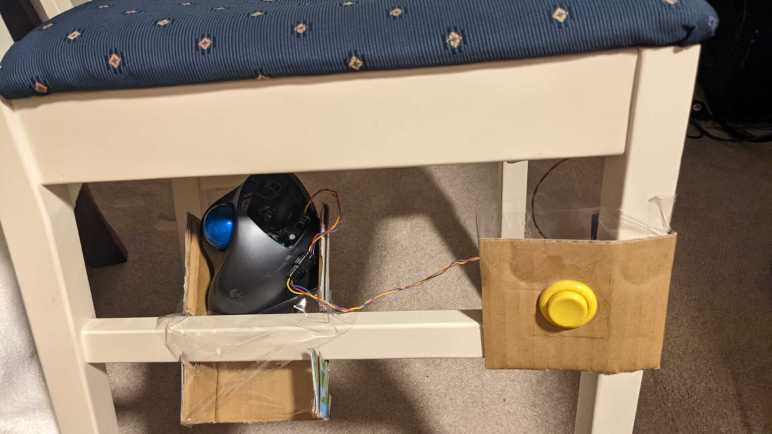

After proving my fan blade LED strobe idea worked with a minimalist Arduino sketch, I ported that code over as an ESPHome custom component. I thought it would be good practice for writing ESPHome custom components and gain Home Assistant benefit of adding adjustments in software. For me it was easier to create an analog control with a few lines of YAML and C, than it would be to wire up a potentiometer. (I recognize it may be the reverse for people more comfortable with hardware than software.)

The first adjustment “Fan Speed Control” actually did not require custom component at all: making the fan speed adjustable utilized the built-in fan speed component. In my minimalist sketch the fan is always running at full speed, now I can adjust fan speed and verify that the strobe logic indeed stays in sync with the fan speed. Meaning the strobe keeps these fan blades visually frozen in the same place regardless of their rotational speed.

The first custom output component adjustment “Strobe Duration” changes the duration of LED strobe pulse, from zero to 1000 microseconds. For this LED array, I found values under 100 to be too dim to be useful. The dimmest usable value is around 100, and things seem to work well up to 300. I start detecting motion blur above 300, and things are pretty smeared out above 600.

The next addition is a toggle switch “Strobe Tachometer Toggle”. Because the tachometer signal pulses twice per revolution, I ignore every other pulse. But that means a 50% chance the code will choose to trigger on the wrong pulse, resulting in a visually upside-down image. When this happens, this toggle allows us to flip to trigger on the opposing pulse, flipping the frozen visual right-side up.

The final custom component adjustment “Strobe Delay” adds a delay between triggered by tachometer wire and illumination of LED strobe. This changes the point at which the fan is visually frozen by the strobe light. Dynamically adjusting this value makes it look like the fan blade is slowly rotating position even though it is actually rotating at ~1200RPM. I think it is a fun effect, but to fully take advantage of that effect I will need longer delays, which means finding how I could move that work outside of my interrupt service routine. Inside the ISR I should set up a hardware timer for this delay and turn on LED when timer expires. I can then use the same mechanism to set a timer for LED duration and turn off LED when that timer expires.

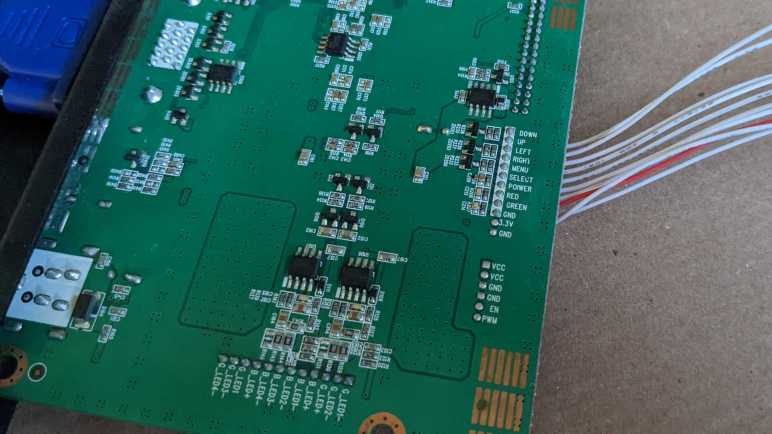

Unfortunately, there are only two hardware timers on an ESP8266, and they are both spoken for. One runs WiFi, the other runs Arduino core for things like millis(). To explore this idea further, I will need to move up to an ESP32 which has additional hardware timers exposed to its Arduino core. And if I choose to explore that path, I don’t even need to redo my circuit board: there exists a (mostly) drop-in ESP32 upgrade for anything that runs a Wemos D1 Mini.

YAML Excerpt:

esphome:

includes:

- led_strobe_component.h

output:

- platform: esp8266_pwm

pin: 14

id: fan_pwm_output

frequency: 1000 Hz

- platform: custom

type: float

lambda: |-

auto led_strobe = new LEDStrobeComponent();

App.register_component(led_strobe);

return {led_strobe};

outputs:

id: strobe_duration_output

- platform: custom

type: float

lambda: |-

auto led_strobe_delay = new LEDStrobeDelayComponent();

App.register_component(led_strobe_delay);

return {led_strobe_delay};

outputs:

id: strobe_delay_output

fan:

- platform: speed

output: fan_pwm_output

id: fan_speed

name: "Fan Speed Control"

light:

- platform: monochromatic

output: strobe_duration_output

id: strobe_duration

name: "Strobe Duration"

gamma_correct: 1.0

- platform: monochromatic

output: strobe_delay_output

id: strobe_delay

name: "Strobe Delay"

gamma_correct: 1.0

switch:

- platform: custom

lambda: |-

auto even_odd_flip = new LEDStrobeEvenOddComponent();

App.register_component(even_odd_flip);

return {even_odd_flip};

switches:

name: "Strobe Tachometer Toggle"

ESPHome custom component file led_strobe_component.h:

#include "esphome.h"

volatile int evenOdd;

volatile int strobeDuration;

volatile int strobeDelay;

IRAM_ATTR void tach_pulse_handler() {

if (0 == evenOdd) {

evenOdd = 1;

} else {

delayMicroseconds(strobeDelay);

digitalWrite(13, HIGH);

delayMicroseconds(strobeDuration);

digitalWrite(13, LOW);

evenOdd = 0;

}

}

class LEDStrobeComponent : public Component, public FloatOutput {

public:

void setup() override {

// LED power transistor starts OFF, which is LOW

pinMode(13, OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(13, LOW);

// Attach interrupt to tachometer wire

pinMode(12, INPUT_PULLUP);

evenOdd = 0;

attachInterrupt(digitalPinToInterrupt(12), tach_pulse_handler, RISING);

strobeDuration = 200;

}

void loop() override {

}

void write_state(float state) override {

// Multiply by 1000 = strobe duration from 0 to 1ms.

strobeDuration = 1000 * state;

}

};

class LEDStrobeEvenOddComponent: public Component, public Switch {

public:

void write_state(bool state) override {

evenOdd = !evenOdd;

publish_state(state);

}

};

class LEDStrobeDelayComponent: public Component, public FloatOutput {

public:

void write_state(float state) override {

strobeDelay = 1000*state;

}

};