When I salvaged LCD for play later, I didn’t know enough about them to make sure I salvaged them with known controllers in working condition. Fortunately, by sheer luck I managed to do that with a car audio head unit. But this adventure started with a talk on direct control of simple LCDs and I wanted to get back to that initial motivation. My most recent LCD salvage was from a Taylor food thermometer, but it didn’t look easy to work with. Due to the fact its electrical contact is in the form of elastomeric “zebra strip” and I didn’t want to build my own circuit board to make contact with it.

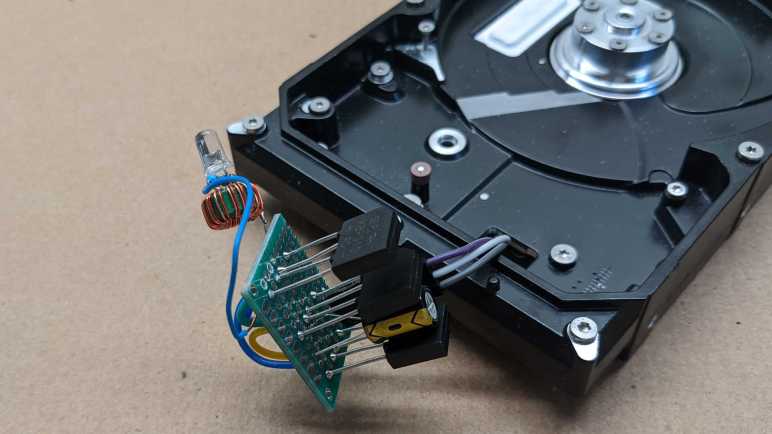

I saved the original circuit board thinking that I could use it as reference when I get around to making my own board. These are just flat rectangles of copper, each one millimeter wide and spaced one millimeter apart. Thanks to Joey Castillo’s Remoticon talk, I learned that bare LCD require very little current so I think the surface area of these contact patches are generous. Perhaps I could get away with using only part of it?

I started soldering wires to these pads, trying to keep my soldered area to less than 25% of the surface area leaving remainder clear for the elastomeric strip.

I then severed all of the original traces to make sure my experimental signals won’t route through the original chip.

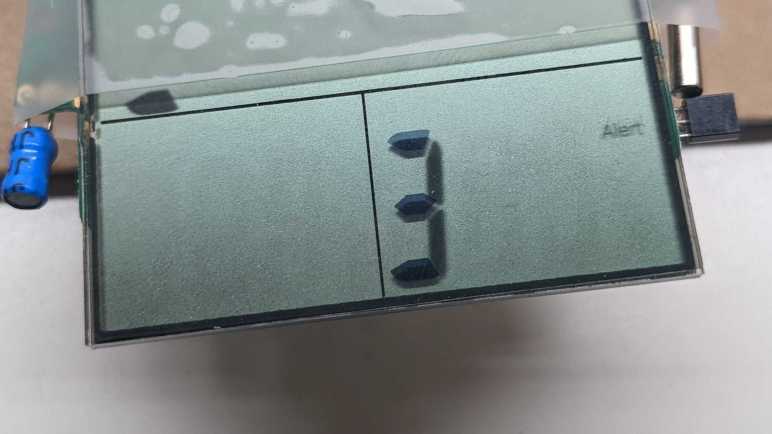

I started probing with alternating signals from an ESP8266 at 3.3V. This is what I see when I put them on the left-most and right-most wires: five segments darken, but one more clearly than the rest. “But wait, I see more than five segments” explanation: the three horizontal lines on that 3 are actually all a single segment, apparently this digit only needs to show a subset of numbers. For example, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9 can be shown with all three horizontal lines active, and 1 can be shown with all three inactive. There are four other dark segments but they are blurry. A horizontal segment in the upper left, two of the vertical segments on that digit, and a fixed text “Alert”.

Further probing found that the left-most five lines and the right-most five lines multiplex against each other, together letting me control 25 segments. Whenever I light one up, four others are blurry. After some experimentation I understand this is due to my voltage too high. Adding a voltage dividing resistor ladder (1 kilo-ohm and 470 ohm) brought it down to 2-ish Volts. Once at that level, individual segments activate cleanly without crosstalk activation of their multiplexing neighbors.

When I tried to get a picture of a single cleanly activated segment, I failed because a wire popped loose. Since this experiment required that I solder these wires to tiny fraction of the pad, these were very bad solder joints with small contact area. They began to fail one by one. Some would pop off cleanly so I knew it failed, others would seem to be physically connected but electrically discontinuous.

I got far enough to determine the multiplex scheme is different from the “common”/”segment” split mentioned in the Remoticon talk and common in multiple other LCD controllers. [Update: I was wrong. See link to update at the bottom of this post.] Figuring out the novel multiplex scheme might be interesting, but not while fighting bad electrical connections at the same time. After a few rounds of “multiplex or bad connection?” guessing game, I got frustrated and decided to postpone this puzzle until I can create better contact with the elastomeric zebra strip. I went looking elsewhere for a simple LCD.

UPDATE: I took another swing at this task and was successful on the second try.