One of my long standing to-do list items is to understand and master control of brushless DC motors. My goal is small robots, so I want to work with motors bigger than tiny multirotor aircraft motors and smaller than beefy electric car motors. Towards the upper range of my interest (before their voltage/amperage start to get scary) are motors used in two-wheeled balance scooters. As a Back to the Future fan, I am offended these devices have been marketed under the name “hoverboard” but that is out of my control.

I’ve been waiting for their prices to drop and they seemed to have settled near the $100 mark. When my local Target advertised a sale dropping a “Jetson Rogue” below $100, I got one with the intent of taking it apart to see what’s inside. But I have yet to do so and it has since gathered a thick layer of dust. It occurred to me I should charge up the battery occasionally. I plugged in the charger and… nothing. Hmm. Not good.

Opening it up, I found its battery pack had a single commodity XT60 connector and nothing else. I can work with that.

I’m mildly concerned by the fact this device had wires that didn’t go anywhere. This white wire has a crimped metal end but it’s not part of any connector I could find.

This properly crimped connector is likewise missing anything to plug into.

Those are mysteries to be solved later. Right now I want to see if the battery is dead or if it can be revived. I unplugged the XT60 connector and measured approximately 3V across its terminals. This is low even for a single cell. The label said it was a 7S2P battery pack with a nominal voltage of 25.9V so yeah, I had waited too long to keep it properly charged. Over-discharging is bad, but it is not necessarily fatal.

I set my bench power supply to deliver up to the full 29.4V appropriate for seven lithium-ion cells in series, but limited to a current of 50 mA. This is 5% of the rate delivered by its charging power adapter and should be very gentle on the battery cells in their delicate over-discharged state. I connected the battery, and my power supply control panel showed power delivery was jumping around. 8V for a second, then no power draw at all for several seconds. Then 9V for a second, and things cut out again. This was unexpected. I disconnected my power supply to investigate further.

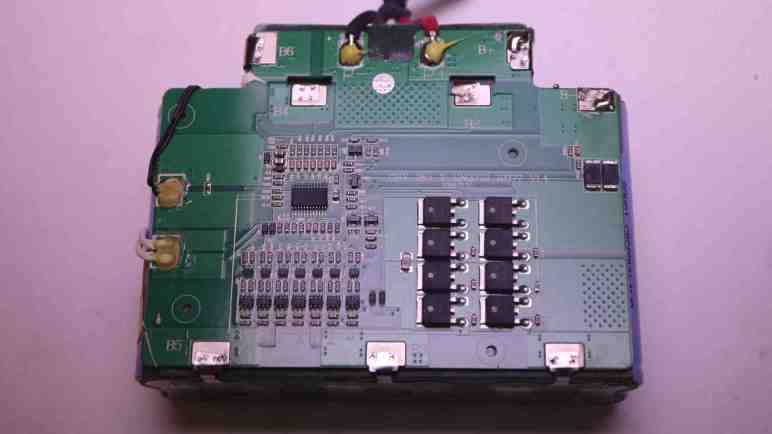

Thankfully this battery pack enclosure was held together with screws, so I could open it up for a look inside. Aha! It is not a raw package of 14 cells in 7S2P configuration, they are under care of a battery management system (BMS) board. Similar to the 3S BMS board I had played with, but this one handles 7S cells. There are spot-welded tabs to monitor voltage of each 2P group. Some of those spot welds are… not textbook, let’s say. But they have continuity and they let me measure voltage. The situation looks even better here. Each 2P group (B- to B1, B1 to B2, etc. through B6 to B+) ranged from 1.1V to 1.9V. The pack as a whole is actually hovering around 10V across its “B+” and “B-” terminals. This is still over-discharged but in far better shape than 3V I measured across output terminals. (P+ and P-)

While the BMS chip is designed to allow charging across P+ and P- terminals, a over-discharged battery is outside of its normal operating range. For reasons I don’t understand, this chip is cutting in and out as I tried to charge with gentle low amperage. The chip may be taking deliberate action to work with over-discharged cells, but it may be getting confused by either the low voltage or my low amperage. There’s a chance the chip’s algorithm is confused and is on a path to destroy itself, the battery cells, or both.

I decided not to trust the chip and go with what I know: steady charge at a gentle low rate. With the pack open, I could connect my bench power supply directly to B+ and B- terminals. This bypassed the BMS chip and allowed me to slowly bring up voltage across the whole pack. Many hours later, pack voltage was up to its nominal 25.9V and I disconnected my power supply. I left the pack sitting overnight so internal chemistries can take its time balancing everything out. It was left outdoors in a bucket, just in case the chemistry decided to get angry. The next day I was happy to see it did not burst into flames. I put it back into the scooter. Now the scooter was willing to power up, and was also willing to take power from its charging adapter. I think we are back in business.