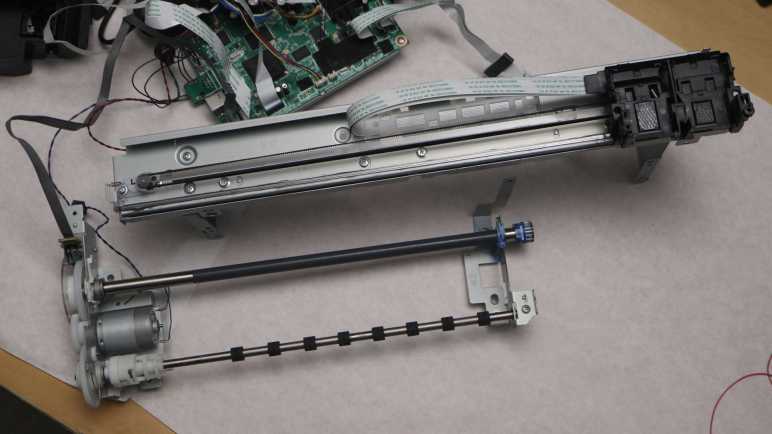

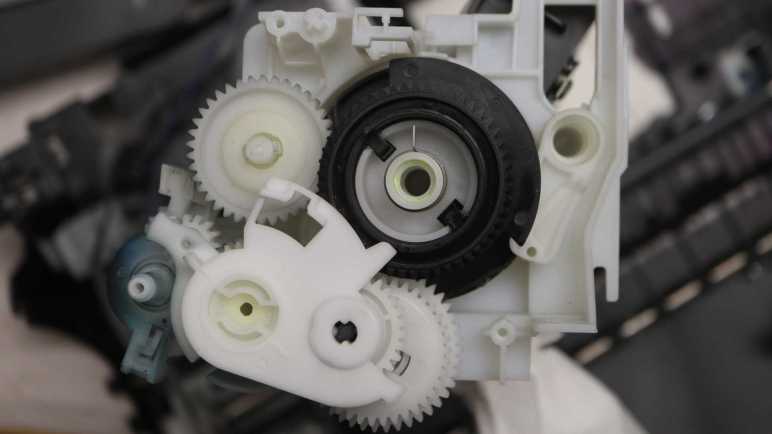

I’ve learned a lot from taking apart my retired Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet, and there are many more potential lessons that I’ve chosen not to pursue. The paper-handling details of its ADF is one, its main circuit board is another. There are a lot of electronics design lessons on this intricate board, but they’re beyond my current skill level to understand. (In comparison, the control panel was a much simpler single-sided circuit board and I enjoyed tracing through it.) But I’ll still take a cursory look at the main board.

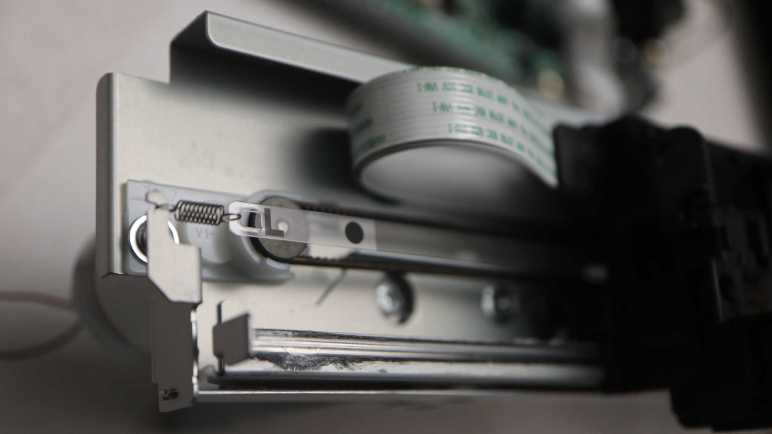

So far, I’ve kept everything plugged in so I could keep it running and probe component interactions. Now I will unplug everything so I can take a look at the board itself. I took many pictures as reference as I went, to increase the odds I can put it back together, but I would later learn it was unnecessary.

Unplugging everything left a large plastic shield.

Removing the shield uncovered the fact that landline phone jacks (for its fax functionality) are on a separate circuit board. I’ve reused salvaged jacks before so these may yet find another use.

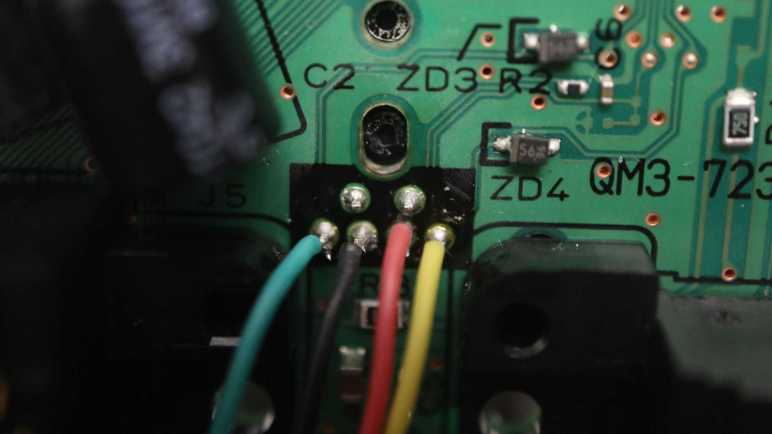

Finally I have the main board by itself. As already stated it’s much more complex than my skill level can reverse-engineer, and I have no motivation to do so anyway.

The circuit board as a minimum of two layers, possibly more but I don’t know enough to tell.

Apparently production volume of mainstream Canon inkjets are high enough to amortize up-front cost of custom electronic components. I picked a few large pieces and tried searching for them based on their markings, coming up empty handed across the board. An example is IC702 here marked with a Texas Instruments logo. It should have been a slam dunk but all I got were chip vendors promising to sell me a TI OACC3TTC 81024 without having any idea what it is. The same story repeated for three other chips before I threw my hands up and quit trying.

There were many unpopulated footprints on the main board, presumably to support features of other models in the product line. I can speculate on two of them. This looks like an Ethernet port, something I would have appreciated as its WiFi module is now out of date due to its WPS dependency.

This unpopulated footprint for connector CN502 is labeled “Card” and has nine pins, matching nine contacts on a SD card. MX340 have a feature for scanning a document directly to PDF file on a USB memory stick. Looks like a sibling model could write out to a SD card.

There were a few other unpopulated footprints but I had no speculation on what they might be. Bringing to a conclusion all I had expected to get out of looking over this circuit board. I plugged everything back in and was mildly surprised it still ran.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here to rewind back to where this adventure started.