It was fun to poke around internal hardware of a tiny PC I wanted to investigate for use as a robot brain. This GMKtec NucBox3 I ordered off Amazon (*) is a more affordable variation on the Intel NUC formula, and its price (significantly lower than Intel’s own NUC) makes me more willing to experiment with it.

Decent PC for Windows 11 Home

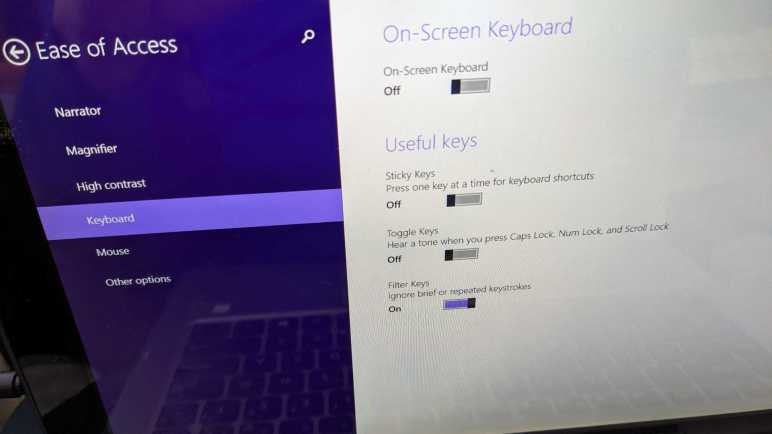

But before I take any risk with nonstandard usage, I should verify it worked as advertised. The 128GB SATA SSD came installed with Windows 11 Home edition build 21H2. Upon signing in with my Microsoft account, it started the update process to build 22H2. I assumed the machine came with a license of Windows either embedded in the hardware or otherwise registered. Windows 11 control panel “Activation state” says “Windows is activated with a digital license linked to your Microsoft account” which I found to be ambiguous. I shrugged because I plan to use it as ROS brain and, if so, I’m likely to run Ubuntu instead of Windows. And if I wipe the SATA drive with a fresh installation of Windows 11, it sounds like I can log in with my Microsoft account and retrieve its license.

The more informative aspect of Windows sign-in and registration is letting me get a feel of the machine in its default configuration. All hardware drivers are in place with no question marks in device manager. Normal user interface tasks were responsive and never frustrating, which is better than certain other budget Windows computers I’ve tried. A NucBox3 is a perfectly competent little Windows box for light duty computer use.

One oddity I found with the NucBox3 was the lack of a power-up screen letting me change boot behavior with a keypress. When a PC first powers up, there’s typically a prompt telling me to press F12 to enter a menu to select a boot device, or DEL to enter system setup, etc. Not on a NucBox3, though: we always boot directly into Windows. The only way I found to enter hardware menu was from within Windows: under “Settings”/”System”/”Recovery” we can choose “Advanced startup” to boot into a special Windows menu, where I can select “Advanced Options” and choose “UEFI Firmware Settings”. This is expected to be an infrequent activity most users would never do, so I guess it’s OK for the process to be a convoluted.

UEFI Menu

Once I got into UEFI menu for NucBox3 I was surprised by how many options are listed. Far more than any branded (Dell, etc) computer I’ve seen and even more than hobbyist-focused motherboards.

Some of these options like “Debug Configuration” almost feel like they weren’t supposed to ship in a final product. My hypothesis is that I’m looking at the default full menu of options for a manufacturer using this AMI (American Megatrends, Inc) UEFI firmware. Maybe the manufacturer was expected to trim it down as appropriate for their product, and maybe nobody bothered to do that.

Under the “Chipset” menu we have device configuration for many peripherals absent from this device. They’re marked [Disabled] but the menu option didn’t even need to be here. The final line was also the most surprising: a selection for resistors on I2C buses. On one hand, I’ve never seen a PC’s I2C hardware exposed in any user-visible form before. On the other hand, if I can figure out where SDA/SCL lines are on this motherboard, maybe I can really have some fun. Why bother with a Raspberry Pi or even an ESP32 to bridge I2C hardware if I can attach them directly to this PC?

Ubuntu Server

But all those shiny lights in UEFI menus were just a distraction. What I really want right now is to control boot sequence so I can boot from a USB flash drive to install Ubuntu Server 22.04 LTS. I found I could do it from the “Boot” section of UEFI menu. Ubuntu Server was installed, it worked, and that was no surprise. A computer competent at a full Windows 11 GUI rarely has a problem with text-based network-centric Ubuntu Server, and indeed I had no problems here. For a ROS brain I would want gigabit networking, all four CPU cores, RAM, storage, and USB peripherals. They are all present and accounted for, even sleep mode if I want to put a robot to sleep.

Variable Input Voltage

The next experiment was to see if this computer is tolerant of variable DC supply voltage. On paper it requires 12V DC and the supplied AC adapter was measured at 12.27V DC. I could buy a boost/buck converter that takes a range of input voltages and output a steady 12V (*) but it would be more efficient to run without such conversion if I could get away with it. Since the NucBox3 used a standard 5.5mm OD barrel jack for DC power input, it was easy to wire it up to my bench power supply. I found it was willing to boot up and run from 10VDC to 12.6VDC, the operating voltage range of 3S LiPo battery packs.

Good ROS Brain Candidate

This little computer successfully ran Ubuntu Server on (simulated) battery power. It handily outperforms the Dell 11 3180 I previously bought as ROS brain candidate and is much more compact for easy integration on robot chassis. Bottom line, I have a winner on my hands here!

I’m glad that Newegg advertisement made me aware of an entire ecosystem of inexpensive small PCs. I need to keep this product category in mind as candidates for potential future projects. I have many options to consider, depending on a project’s needs.

(*) Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.