After attending Elecia White’s “On Cats and Typing” talk, I felt a little more motivated to look into robots. The robot arm used in her demo was the MeArm by Mime Industries. It is built out of commodity micro servos and laser-cut acrylic. I looked at it and thought I could get one up and running on my own. It is sold as a self-assembled kit but in the spirit of open source, people are also allowed to laser-cut their own pieces using the open-sourced DXF file available via Github.

Or at least that was the theory.

In practice, the DXF doesn’t work. Inkscape couldn’t load it. CorelDRAW couldn’t load it. Onshape couldn’t load it. Fusion 360 – from Autodesk, the people who created AutoCAD which is where DXF came from – couldn’t load it.

Well, that was disappointing.

Google results confirm I’m not alone. I found many reports of people failing to get this DXF to work for them, and not a single success story. Of course, there’s a little selection bias here: people who encounter no problems rarely go on the internet to announce they had no problems. But I would have expected a few of the forum posts from people having problems to get some positive responses, and I didn’t find any of those.

This is frustrating. I’m unlikely to go and buy the kit when I already had most of the pieces on hand and it is in theory open source for me to make my own. It’s impossible to tell if there’s a perfectly innocent explanation or if this was done maliciously to slap on the “open source” label without actually risking any cut into sales. Whatever the explanation for why this DXF is broken, it doesn’t change the fact that it is broken. When the publicly available source file is unusable. Is it still open source?

I vote no.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes follow-up to the LED test fixtures of the previous few posts: when we only need a simple circuit for a 3D-printed project, we can meld the two instead of using a formal circuit board. In this context “meld” is meant literally: the parts of the circuit can be heated up with the soldering iron so they melt into the 3D printer plastic.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes follow-up to the LED test fixtures of the previous few posts: when we only need a simple circuit for a 3D-printed project, we can meld the two instead of using a formal circuit board. In this context “meld” is meant literally: the parts of the circuit can be heated up with the soldering iron so they melt into the 3D printer plastic.

Portable External Monitor version 2.0 (PEM2) explored a different construction technique from PEM1. Instead of building a box by assembling its six side pieces (top, bottom, left, right, front back) the box is built up by stacking sheets of acrylic.

Portable External Monitor version 2.0 (PEM2) explored a different construction technique from PEM1. Instead of building a box by assembling its six side pieces (top, bottom, left, right, front back) the box is built up by stacking sheets of acrylic.

Once the LCD panel and matching frame had been salvaged from the laptop, it’s time to build an enclosure to hold it and the associated driver board together. Since this was only the first draft, I was not very aggressive about packing the components tightly. It’s merely a simple big box to hold all the bits checking to see if I have all the mounting dimensions for all the circuit boards correct.

Once the LCD panel and matching frame had been salvaged from the laptop, it’s time to build an enclosure to hold it and the associated driver board together. Since this was only the first draft, I was not very aggressive about packing the components tightly. It’s merely a simple big box to hold all the bits checking to see if I have all the mounting dimensions for all the circuit boards correct.

In the previous post, the laser cutter kerf was successfully compensated, admittedly in a way that left plenty of room for improvement in the future. This post will look at a different challenge of building with acrylic: variation in thickness of acrylic sheets. So far experience showed different sheets of “6 mm” acrylic can actually be anywhere from 5.31 mm to 6.03 mm.

In the previous post, the laser cutter kerf was successfully compensated, admittedly in a way that left plenty of room for improvement in the future. This post will look at a different challenge of building with acrylic: variation in thickness of acrylic sheets. So far experience showed different sheets of “6 mm” acrylic can actually be anywhere from 5.31 mm to 6.03 mm.

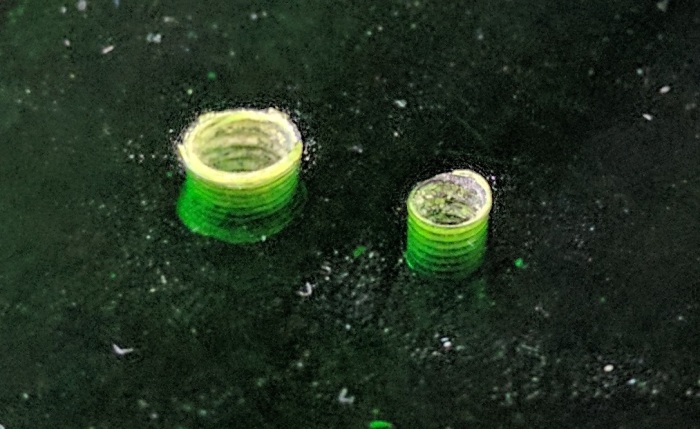

Since my last fixture project was foiled by laser cutter kerf, I thought I’d try 3D printing the next fixture to avoid laser cutter kerf spoiling my fixture accuracy.

Since my last fixture project was foiled by laser cutter kerf, I thought I’d try 3D printing the next fixture to avoid laser cutter kerf spoiling my fixture accuracy. The end result demonstrated that, even though a 3D printer does not have cutter kerf to compensate for, it introduces other errors in the system. Maybe expensive industrial 3D printers would have enough accuracy to make this fixture work, but my little hobbyist level printer definitely did not. The corners of the box did not mate together as precisely as it did in my mind. The gaps are too wide and uneven for acrylic cement to bridge.

The end result demonstrated that, even though a 3D printer does not have cutter kerf to compensate for, it introduces other errors in the system. Maybe expensive industrial 3D printers would have enough accuracy to make this fixture work, but my little hobbyist level printer definitely did not. The corners of the box did not mate together as precisely as it did in my mind. The gaps are too wide and uneven for acrylic cement to bridge.