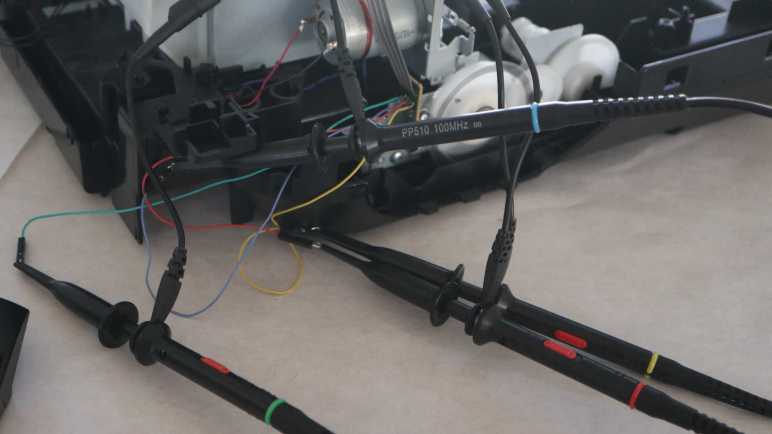

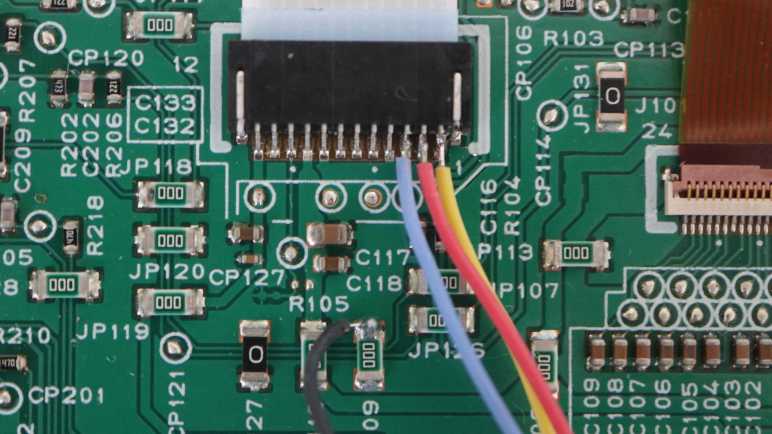

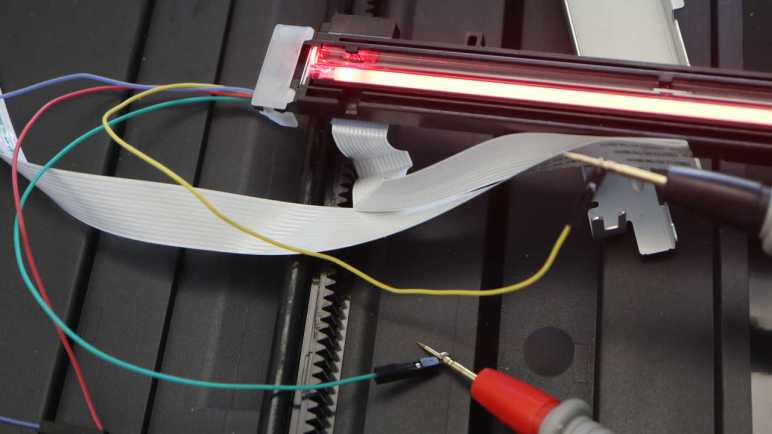

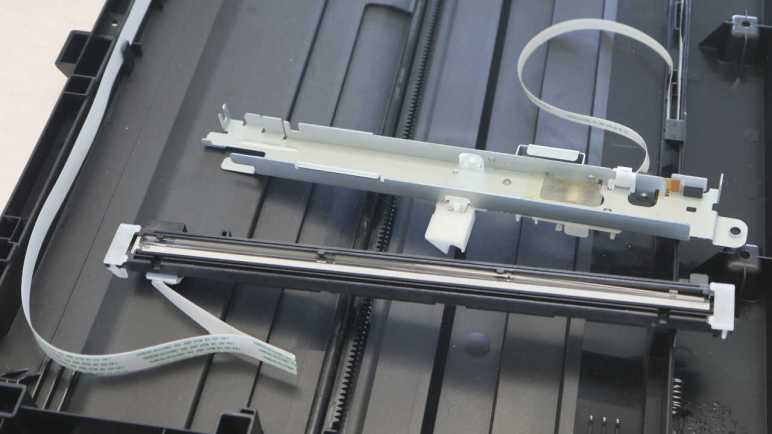

I’m on a side quest decoding motion reported by the quadrature encoder attached to the paper feed motor of a Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet. Recording encoder counts was easy and gave me some preliminary insights into the system, but now I want to make my data probe smarter and parse those encoder positions into movements. This has proven more challenging. In an effort to keep the project relatively simple, I’m trying “microseconds per encoder count” as a metric that should be easy to calculate with integer math. This is the reciprocal of the more straightforward “encoder count per microsecond” velocity measurement and I hope I can get all the same insights.

I expect “microseconds per encoder count” (shortened to us/enc for the rest of this post) would be low when the motor is spinning rapidly, and high when it is spinning slowly. Above a certain threshold, the system is spinning slowly enough to be treated as effectively stopped.

Based on this expectation, I should be able to divide up recorded positions into a list of movements. The start and end of each movement should be a spike in us/enc that would be high but below “effectively stopped” threshold. These spikes should correspond to acceleration & deceleration on either end of a movement. I revisited the system startup sequence with a rough draft and Excel generated this graph. The blue line is the familiar position graph of encoder counts, and orange line is my new us/enc value.

The best news is that us/enc worked really well for my biggest worry between 15 and 16 seconds, on either side of blue line peak. The motor decelerated then accelerated again in the same direction, something I couldn’t pick up before. Now I see nice sharp orange spike marking each of those transitions on either side of the spike corresponding to direction reversal.

The most worrisome news is that, right after the 13 second mark when the system started its long roll towards the peak, there was barely a spike when its acceleration should have shown up as a more significant signal. I have to figure out what happened there. It may reflect a fatal flaw with this us/enc approach.

Less worrisome but also problematic are the extraneous noisy spikes on the orange us/enc line that had no corresponding movement on the blue position line. Majority of which occurred between 8 and ~10.75 seconds. During this time, the print carriage is moving across its entire range of motion (likely a homing sequence) and that vibration caused a few encoder ticks of motion in the paper feed roller mechanism. I think such small movements can be filtered out pretty easily.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here to rewind back to where this adventure started.

Captured CSV and Excel worksheets are included in the companion GitHub repository.