Trying to revive the LED backlight from a LG Lp133WF2(SP)(A1) laptop display panel, I am focused on a TPS61187 LED driver chip on its integrated circuit board. After studying its datasheet, I soldered a few wires to key parts of the circuit and applied power, checking the circuit as I went. Nothing has gone obviously wrong yet, so the final step is to give that driver chip a PWM signal to dictate brightness.

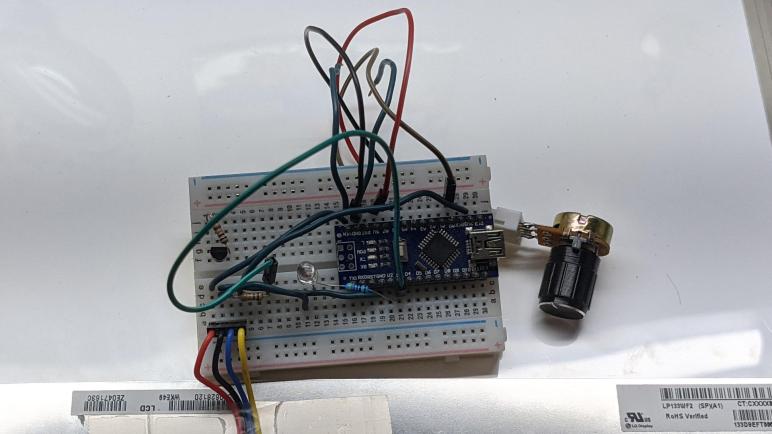

This is where I am happy I’ve added Arduino to my toolbox, because I was able to whip up a controllable PWM signal generator in minutes. Putting an Arduino Nano onto a breadboard, I wired up a potentiometer to act as interactive input. 5V power and ground were shared with the panel, and one of the PWM-capable output pins was connected to the TPS61187 PWM input line via a 10 kΩ resistor as per datasheet. I found that my enable line already had a 1 kΩ resistor on board, so now I wired enable directly to the 5V line.

Since I wanted some confidence in my circuit before plugging the panel into the circuit, I also wired a test LED in parallel with the PWM signal line. I had originally thought I could use the LED already on board the Arduino, but that is hard-wired to pin 13 which is not one of the PWM-capable pins, so the external LED was necessary for me to run my PWM-generating test code, which thanks to the Arduino framework was as easy as:

int sensorPin = A0; // select the input pin for the potentiometer

int ledPin = 3; // select the pin for the LED

int sensorValue = 0; // variable to store the value coming from the sensor

void setup() {

// declare the ledPin as an OUTPUT:

pinMode(ledPin, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

// read potentiometer position

sensorValue = analogRead(sensorPin);

// map analogRead() range to analogWrite() range

sensorValue = map(sensorValue, 0, 1023, 0, 255);

analogWrite(ledPin, sensorValue);

}My external test LED brightened and dimmed in response to potentiometer knob turns, so that looked good. My heart started racing as I connected the panel to my Arduino breadboard, which is then connected to my benchtop power supply. Even though I’m powering this system with 5V, I used a bench power supply instead of a USB port. Because I didn’t know how much the panel drew and didn’t want to risk damaging my computer. Also, by using a benchtop power supply I could monitor the current draw and also set a limit of 120mA (20mA spread across 6 strings) for the first test.

I powered up the system with the potentiometer set to minimum, then slowly started turning the knob clockwise…

It lit up! It lit up! Woohoo!

I was very excited at this success, jumping and running down the hallway. It was a wild few minutes before I could settle down and calmly take a closer look.