[UPDATE: After installing Proxmox VE kernel update from 6.2.16-15-pve to 6.2.16-18-pve, this problem no longer occurs, allowing the machine to stay connected to the network.]

I’ve configured an old 15″ laptop into a light-duty virtualization server running Proxmox VE, and I’m running into a reliability problem with the Ethernet controller on this Dell Inspiron 7577. My symptoms line up with a bug that others have filed, and a change to address the issue is working its way through the pipeline. I wouldn’t call it a fix, exactly, as the problem seems to be flawed power management in Realtek hardware and/or driver in combination with the latest Linux kernel. The upcoming change doesn’t fix Realtek power management, it merely disables their participation in PCIe ASPM (Active State Power Management).

Until that change arrives, one of the mitigation workarounds is to deactivate ASPM on the entire PCIe bus. There are a lot of components on that bus! Here’s the output from running “lspci” at the command line:

00:00.0 Host bridge: Intel Corporation Xeon E3-1200 v6/7th Gen Core Processor Host Bridge/DRAM Registers (rev 05)

00:01.0 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 6th-10th Gen Core Processor PCIe Controller (x16) (rev 05)

00:02.0 VGA compatible controller: Intel Corporation HD Graphics 630 (rev 04)

00:04.0 Signal processing controller: Intel Corporation Xeon E3-1200 v5/E3-1500 v5/6th Gen Core Processor Thermal Subsystem (rev 05)

00:14.0 USB controller: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family USB 3.0 xHCI Controller (rev 31)

00:14.2 Signal processing controller: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family Thermal Subsystem (rev 31)

00:15.0 Signal processing controller: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family Serial IO I2C Controller #0 (rev 31)

00:15.1 Signal processing controller: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family Serial IO I2C Controller #1 (rev 31)

00:16.0 Communication controller: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family MEI Controller #1 (rev 31)

00:17.0 SATA controller: Intel Corporation HM170/QM170 Chipset SATA Controller [AHCI Mode] (rev 31)

00:1c.0 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port #1 (rev f1)

00:1c.4 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port #5 (rev f1)

00:1c.5 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port #6 (rev f1)

00:1d.0 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family PCI Express Root Port #9 (rev f1)

00:1f.0 ISA bridge: Intel Corporation HM175 Chipset LPC/eSPI Controller (rev 31)

00:1f.2 Memory controller: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family Power Management Controller (rev 31)

00:1f.3 Audio device: Intel Corporation CM238 HD Audio Controller (rev 31)

00:1f.4 SMBus: Intel Corporation 100 Series/C230 Series Chipset Family SMBus (rev 31)

01:00.0 VGA compatible controller: NVIDIA Corporation GP106M [GeForce GTX 1060 Mobile] (rev a1)

01:00.1 Audio device: NVIDIA Corporation GP106 High Definition Audio Controller (rev a1)

3b:00.0 Ethernet controller: Realtek Semiconductor Co., Ltd. RTL8111/8168/8411 PCI Express Gigabit Ethernet Controller (rev 15)

3c:00.0 Network controller: Intel Corporation Wireless 8265 / 8275 (rev 78)

3d:00.0 Non-Volatile memory controller: Intel Corporation Device f1aa (rev 03)Deactivating APSM across the board will impact far more than the Realtek chip. I was curious what impact this would have on power consumption and decided to dig up my Kill-a-Watt meter for some before/after measurements.

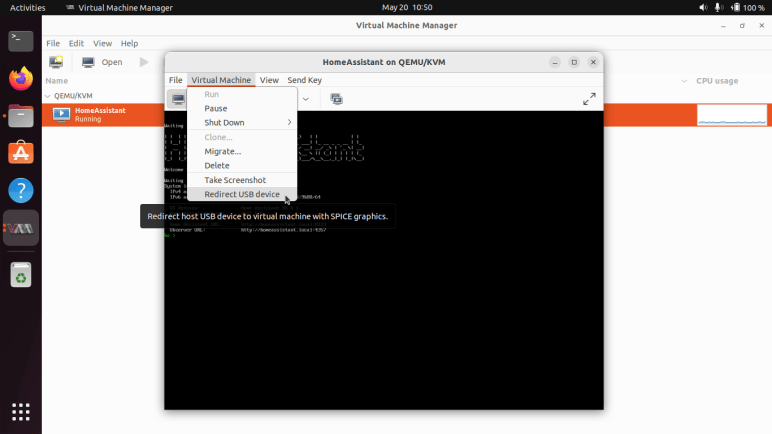

Dell Latitude E6230 + Ubuntu Desktop

As a point of comparison, I had measured a few values of Dell Latitude E6230 I had just retired. These are the lowest values I could see within a ~15 second window. It would jump up by a watt or two for a few seconds before dropping.

- 5W: idle.

- 8W: hosting Home Assistant OS under KVM but not doing anything intensive.

- 35W: 100% CPU utilization as HAOS compiled ESPHome firmware updates.

As a light-duty server, the most important value here is the 8W value, because that’s what it will be drawing most of the time.

Dell Inspiron 7577 + Proxmox VM

Since the Inspiron 7577 came with a beefy 180W AC power adapter (versus the 60W unit of the E6230) I was not optimistic about its power consumption. As a newer larger more power-hungry machine, I had expected idle power draw at least double that of the E6230. I was very pleasantly surprised. Running Proxmox VE but with all VMs shut down, the Kill-a-Watt indicated a rock solid two watts. Two!

As I started up my three virtual machines (Home Assistant OS, Plex, and InfluxDB), it jumped up to fifteen watts then gradually ramped back down to two watts as those VMs reached steady state. After that, it would occasionally jump up to four or five watts for a few seconds to service those mostly-idle VMs, then drop back down to two watts.

On the upside, it appears four generations of Intel CPU and laptop evolution has provided significant improvements in power efficiency. However, they were running different software so some of that difference might be credited to Ubuntu Desktop versus Proxmox.

On the downside, the Kill-a-Watt only measures down to whole watts with no fractional numbers. So a baseline of two watts isn’t very useful because it would take a 50% change in power consumption to show up in Kill-a-Watt numbers. I know running three VMs would take some power, but idling with and without VM both bottomed out at two watts. This puts me into measurement error territory. I need finer grained instrumentation to make meaningful measurements, but I’m not willing to pay money for just a curiosity experiment. I shrugged and kept going.

Dell Inspiron 7577 + Proxmox VM + pcie_aspm=off

Reading Ubuntu bug #2031537 I saw one of their investigative steps was to add pcie_aspm=off to the kernel command line. To follow in those footsteps, I first needed to learn what that meant. I could confirm it is documented as a valid kernel command line parameter. Then I had to find instructions on how to add such a thing, which involved editing /etc/default/grub then running update-grub. And finally, after the system rebooted, I could confirm the command line was processed by typing “cat /proc/cmdline“. I don’t know how to verify it actually took effect, though, except by observing system behavior changes.

The first data point is power consumption: now when hosting my three virtual machines, the Kill-a-Watt showed three watts most of the time. It still occasionally dips down to two watts for a second or two, but most of the time it hovers at three watts plus the occasional spike up to four or five watts. Given the coarse granularity, it’s inconclusive whether this reflects actual change or just random.

The second and more important data point is: did it improve Ethernet reliability? Sadly it did not. Before I made this change, I noted three failures from Realtek Ethernet. Each session lasting 36 hours or less. The first reboot after this change lost network after 50 hours. This might be within range of random error (meaning maybe pcie_aspm=off didn’t actually change anything) and definitely not long enough. After that reboot, the system fell off the network again after less than 3 hours. (2 hours 55 minutes!) That is a complete fail.

I’m sad pcie_aspm=off turned out to be a bust. So what’s next? First I need to move these virtual machines to another physical machine, which was a handy excuse to play with Proxmox clusters.