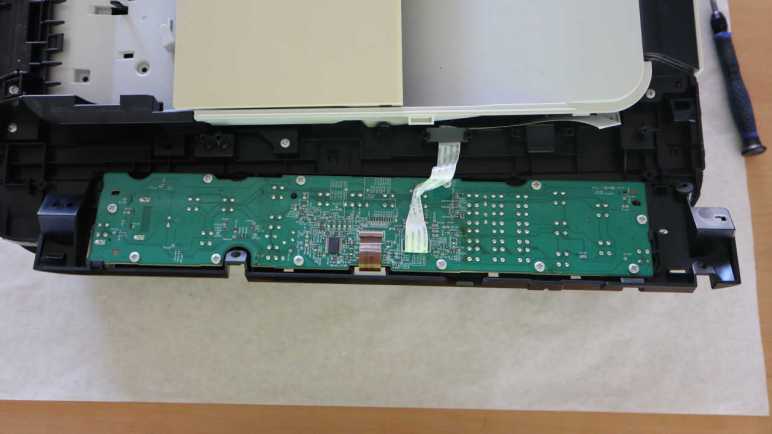

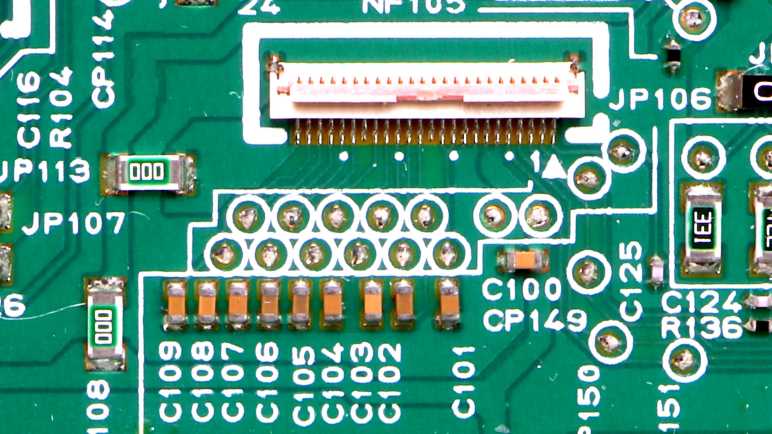

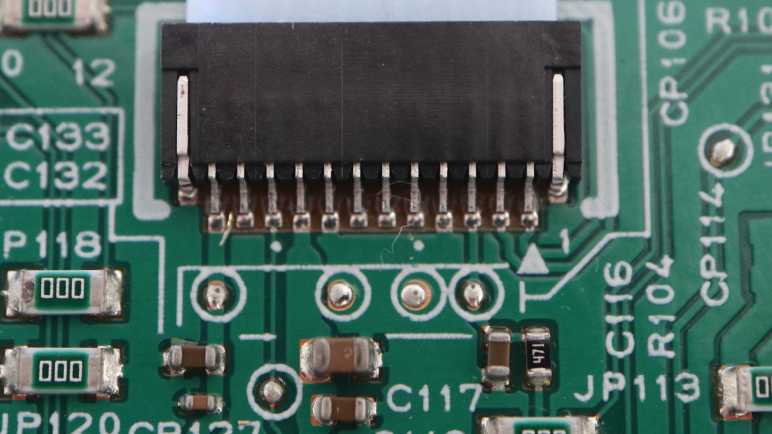

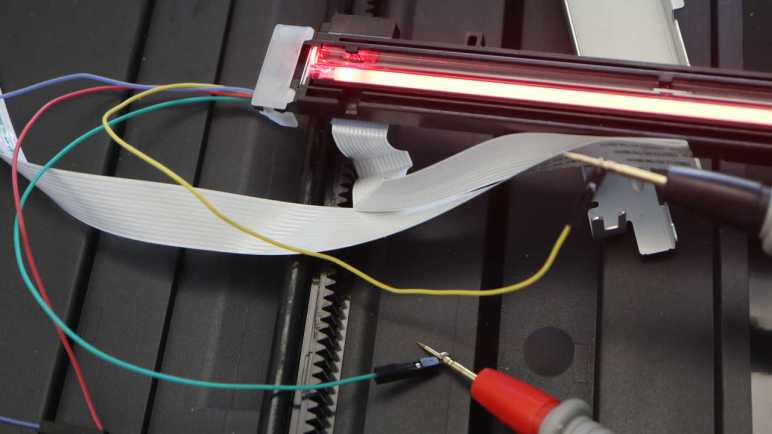

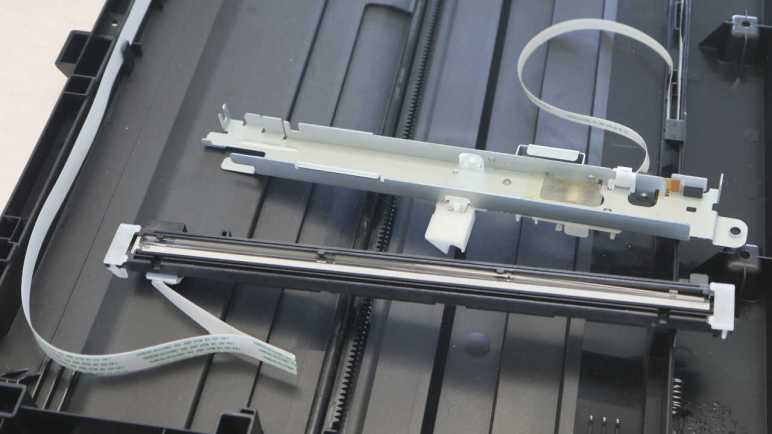

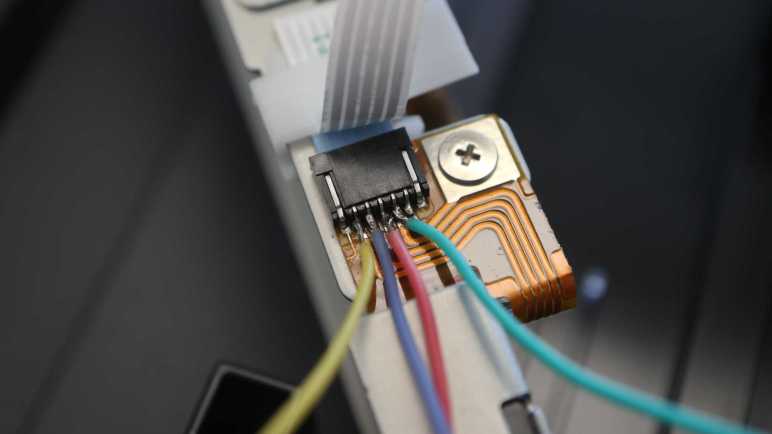

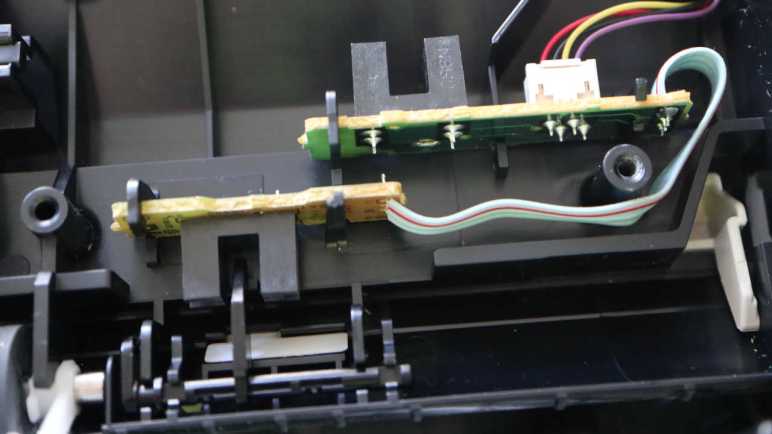

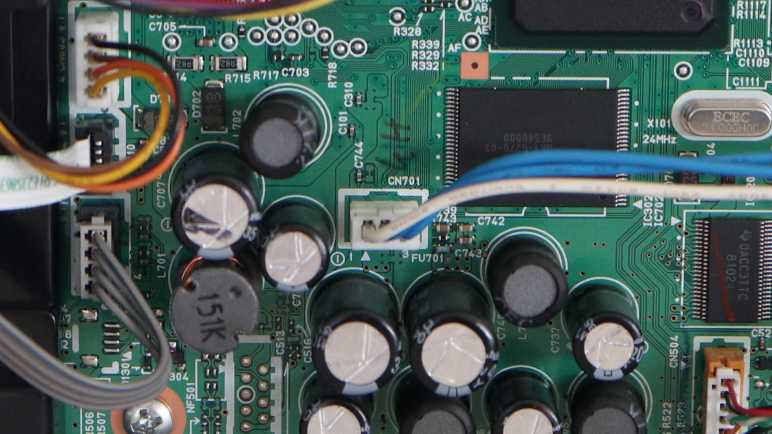

Poking around internals of a retired Canon Pixma MX340 multi-function inkjet, I decided its control panel circuit board was within my skill level to decipher. After following a set of five wires from control board LCD screen to the biggest chip on the board, I think the next effort is to trace out the relationship between that chip and all components on this circuit board. I started doing this by eye but the traces are thin, the contrast is low, and my eyesight isn’t what it used to be. If I will be tackling many more similar projects, I might invest in a magnifier or microscope designed for circuit board work. But for today, I’ll use what I already have on hand: taking pictures with my camera + macro lens then stitch them together.

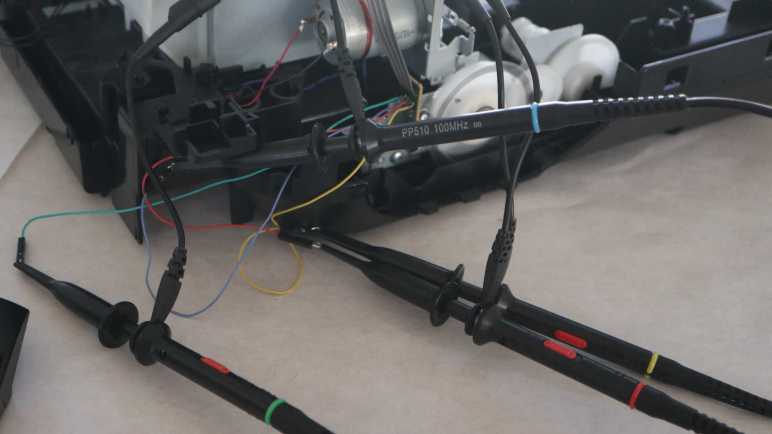

In order to keep the circuit board traces as well as surface component markings in focus, I need to narrow the aperture for greater depth of field. I also wanted to use my polarizing filter to eliminate glare. Both decisions reduced the amount of light reaching my camera sensor. To compensate, I can increase sensitivity, but that adds noise and I don’t want a noisy picture when looking at fine copper traces. The alternate solution is to increase shutter time, which meant setting up my tripod to keep my camera steady during long duration shots. I ended up using an 8 second shutter time in order to stay at low noise ISO 100 sensitivity.

For each picture, I wanted to fill my imaging area with circuit board. The aspect ratio of the circuit board meant I could cover the entire width with four pictures. However, that means a seam somewhere in the middle where all the important bits (main board connector, LCD connector) are located so I decided to take five pictures. One center shot with all the important bits together in one shot, then two pictures on either side.

Once I had the pictures, I brought them into my photo editor putting each image into its own layer. I brought the center image to the foreground, the edge most images to the back, and intermediate images between them. I then scaled image in each layer so all the copper circuit traces lined up at the edges. Looks like I didn’t manage to maintain distance between camera and circuit board, because this resulted in a slightly trapezoidal shape.

After the traces were all lined up, I adjusted image color levels to bring out contrast of copper circuit traces. Doing this meant blowing out bright parts and dark details got crushed, but I decided that’s not important for this project. I also decided not to worry about the fact seams are very noticeable, because color balance changed between pictures.

I didn’t use panorama photo stitching software here because they have different goals. They fix color balance, warp perspective, and blend edges to create a pretty picture. For this project, I’m not looking for pretty, I’m looking for accurate. When I’m following a copper trace across the board, I want to be confident I’m following real untouched data and not misled by something that had been modified to look pretty.

Here is a low-resolution version of the result. If anyone else wants a look, the full resolution version (and original set of five images) are up on my GitHub as they are too large to be hosted here. Obviously I’ll use the full resolution version for further circuit board exploration.

This teardown ran far longer than I originally thought it would. Click here for the starting point.