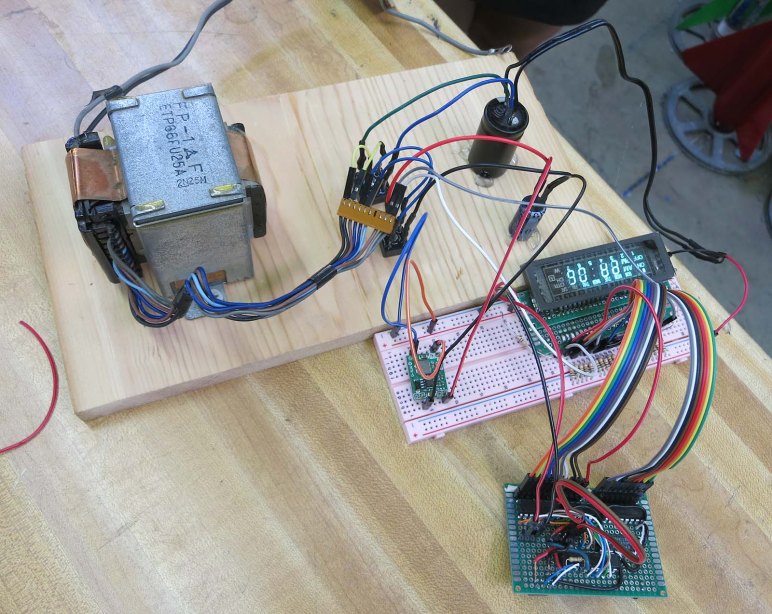

Learning Arduino has finally moved from a back burner to the front, and as a first step I finally unpackaged a years-old purchase of an Arduino Uno compatible board. Enough years have passed that particular board has become obsolete, but the Arduino ecosystem is still going strong so chances are good that I can still use the board to learn.

The first step with new hardware is always testing out some sort of a “Hello World” demo program to make sure the basics are working. When it comes to playing with electronics hardware, the popular choice is to blink a LED. This is such an entrenched thing that Arduino has designed a LED into their boards perfectly suited for the purpose, and my Arduino-compatible board has copied that arrangement.

Following the “Getting Started” guide for an Arduino Uno, I installed Arduino’s Desktop IDE. The basic example blink program was only a few clicks away, and an Arduino Uno was already selected as the target board type. Once I selected the serial port to use for communication, I was able to click on “Upload”. After a few seconds, I could see the test LED blinking on my board. It lives!

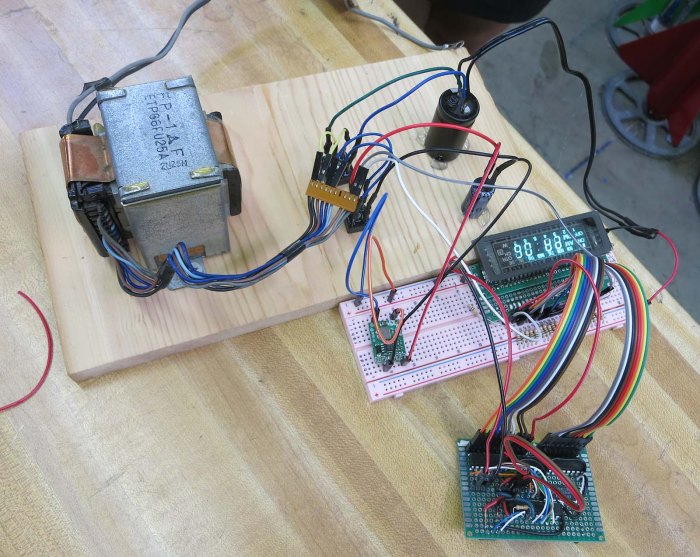

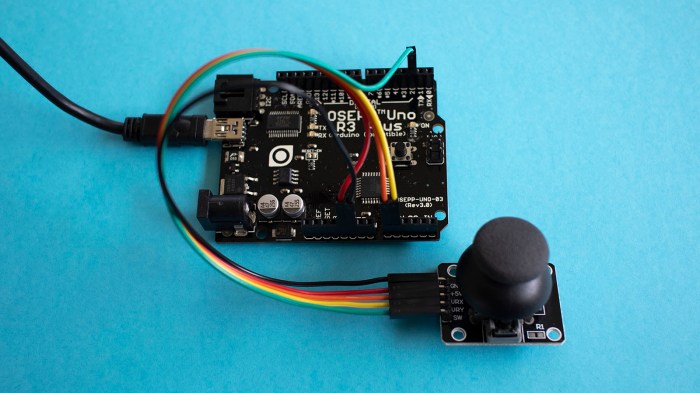

Success of that fundamental test gave me confidence to move on and add some hardware. I had bought some small joystick modules (*) for this purposes of building my own Arduino based controller. Like most joysticks, they are built around a pair of potentiometers which made them an easy match for Arduino joystick tutorial.

As many reviewers warned in that Amazon product listing, these joystick modules are very sensitive to movement. Their electrical range of motion is a surprisingly small subset of their actual physical range of motion. In other words, the potentiometers reach their minimum/maximum electrical values when the stick has only moved barely a third or halfway into its physical range of motion. This will be good for quick reaction movements but not as good for fine pitched movement.

These joysticks might not be the best ones for the job of rover control, but they will work well enough for continued Arduino exploration.

(*) Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.