Electric blankets are an energy-efficiency way to stay warm during cold nights. If I’m going to stay in bed while sleeping, why heat the whole house? Heat just the bed and get a comfortable rest. But they don’t last forever, and this particular Queen-sized blanket stopped heating for unknown reasons. I’m going to take apart its two control units (one for each half of the bed) to see what’s inside.

According to the label, this is a Sunbeam PAC-215 STYLE 85KQP with a maximum power draw of 360 watts. I interpret PAC-215 to mean the functional designation and 85KQP to mean a specific cosmetic variation, but that’s just a guess. (And it doesn’t affect a teardown, anyway.)

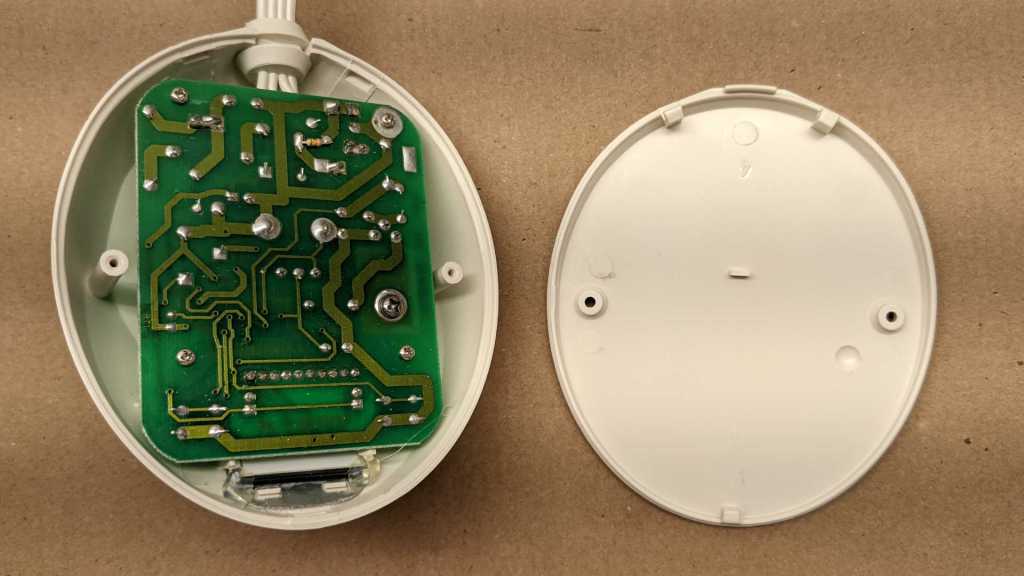

Peeling back all the adhesive circles unveiled two Philips-head fasteners.

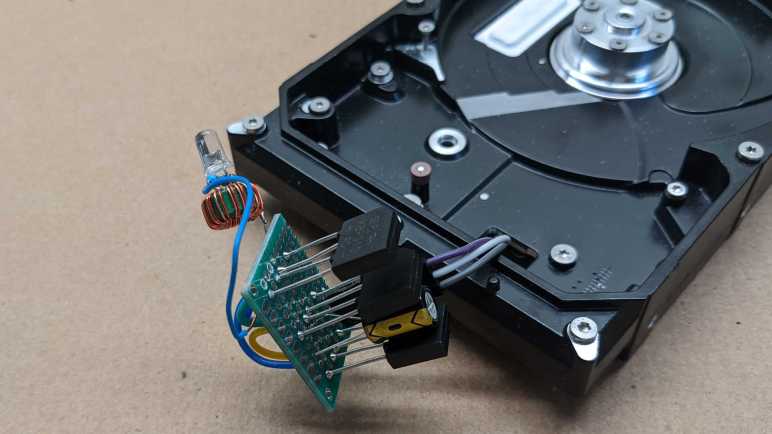

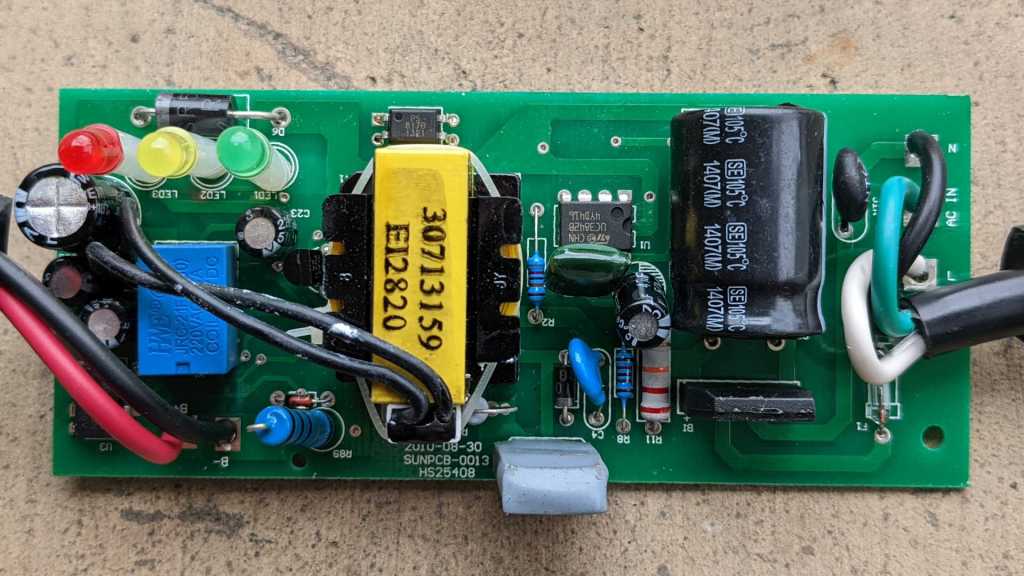

Once those two fasteners were removed, there were three plastic clips to undo before the bottom could be separated from the enclosure. We see many thick traces and wires of through-hole components. Four small Philips-head fasteners hold the circuit board in place, the larger fifth fastener is for the heat sink and can be left in place.

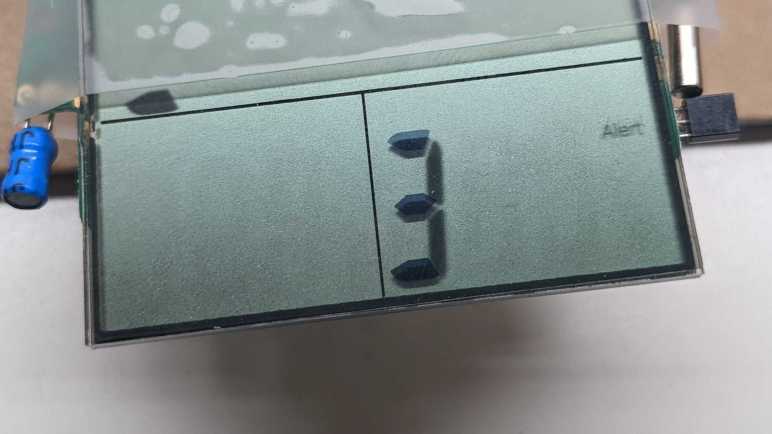

In addition to those four fasteners, the LCD is held by two plastic clips and blobs of hot glue.

Once removed, we could separate the circuit board from the enclosure. Curiously, I see a sheet of metal glued to enclosure top conducting from one of the four screws out to the front of the display area. It might be for grounding purposes, but there is no other metal for it to make contact. It’s not obvious to me what user scenario justified this effort.

I was amused to see that backlight for the LCD is just a pair of LEDs soldered to the board. Simple, straightforward, and functional. No fancy multi-layer light diffusers for this screen.

The circuit board has a white silkscreen marking of PEP003-0A.pcb on the left and a copper marking of FR4(94V-0) DD2 REVB on the right. This picture was rotated 180 degrees relative to earlier pictures to better read identifier on the large surface-mounted IC.

DD2ZW2-3

MP9ACO218E

KOREAI can make out the ST logo but a search for “DD2ZW2” and “MP9ACO218E” on their site both came up empty. Based on the traces going directly to the LCD, this chip has LCD control capabilities. How much more? I don’t know. It might be a complete electric blanket controller solution for all I know. The other item with a ST logo is a BTB06 triac.

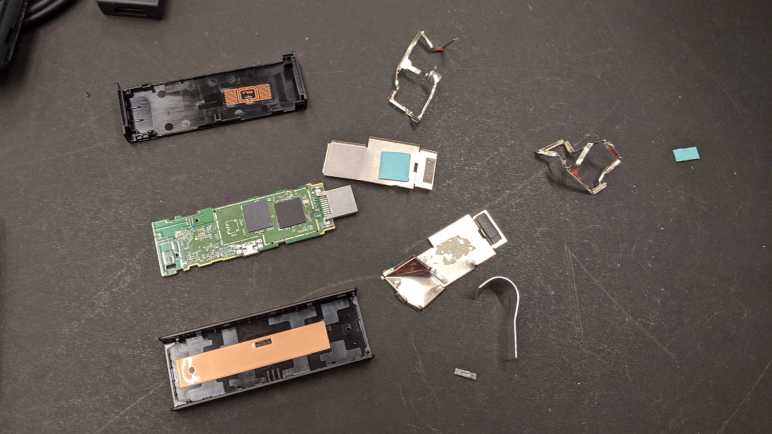

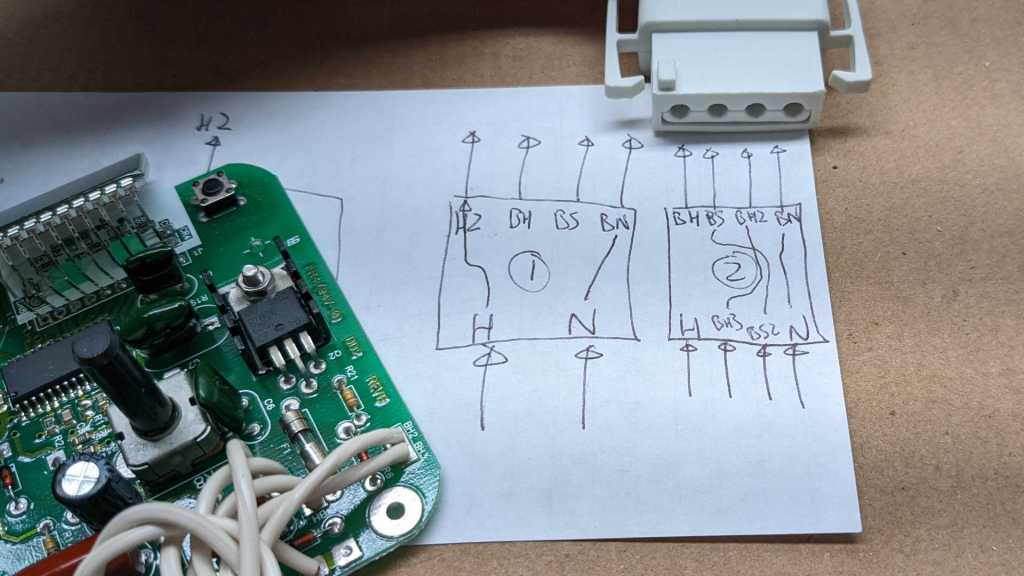

I then proceeded to disassemble the other controller, whose enclosure came apart the same way. I had expected to find two different circuit boards: a primary controller with majority of logic and a secondary unit purely for user interface purposes. I was wrong: the two circuit boards are identical. They only differ in how wires were soldered to each board. I followed their paths and drew a crude diagram.

The power plug enters the first unit and connected to points labeled “H” (Hot) and “N” (Neutral). These are forwarded to the second unit as H2 and BN, respectively. H2 enters the second unit at its own “H” and BN goes to the second unit’s “N”.

Outputs of the first unit are labeled BH and BS, which enters the second unit as BH3 and BS2, respectively, and forwarded on to exit points BH2 and BS. The second unit’s own output goes out as BH, and neutral is forwarded out to the blanket plug.

The blanket plug itself was interesting. It was made of injection-molded plastic and designed to allow loose tolerances due to the flexible nature of the plastic yet still offer lots of mechanical strain relief.

The story continues inside, with plenty of strain relief considerations. This should nearly eliminate any mechanical stress from acting on the four crimped electrical connectors.

This teardown was more interesting than I had expected, as the controllers were more sophisticated than I had given them credit for. That was fun in its own right. But the motivation for doing this teardown today (instead of later) was so I could get my hands on some simple bare LCD modules I could play with.