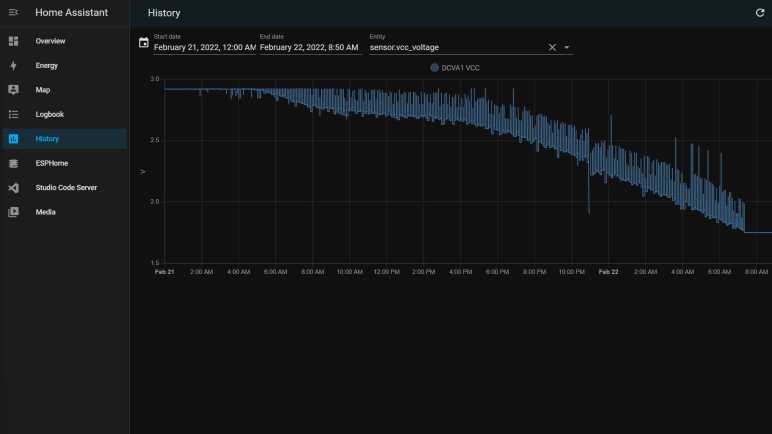

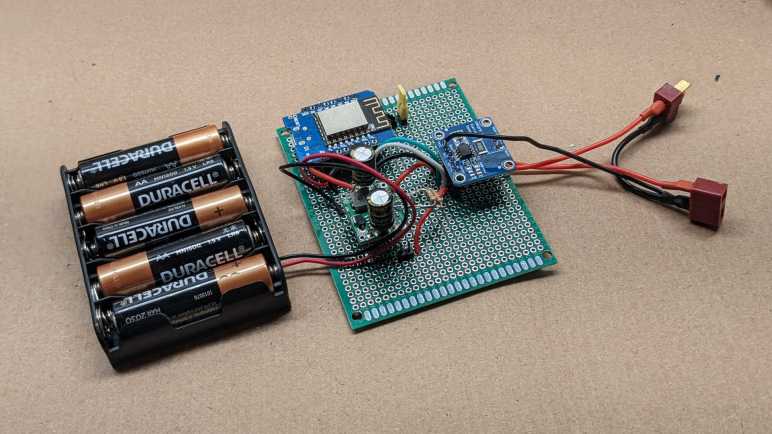

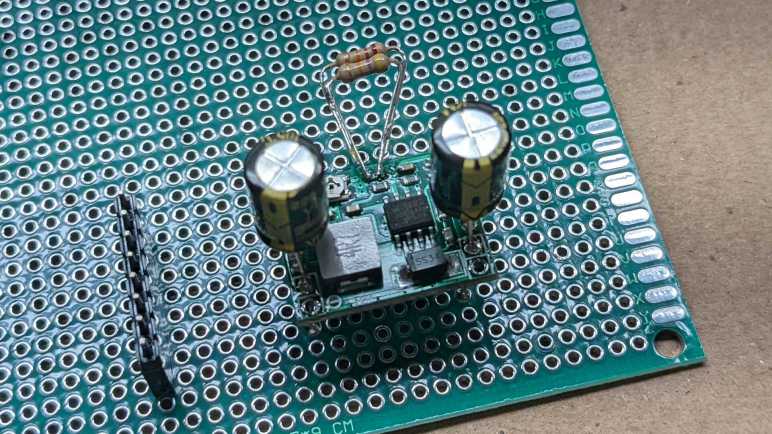

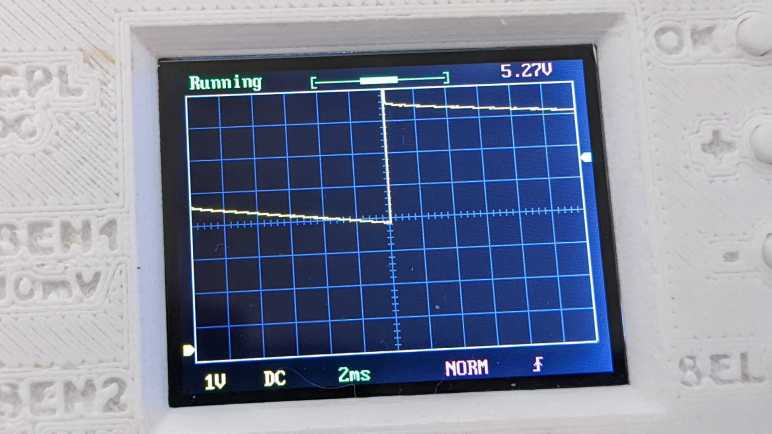

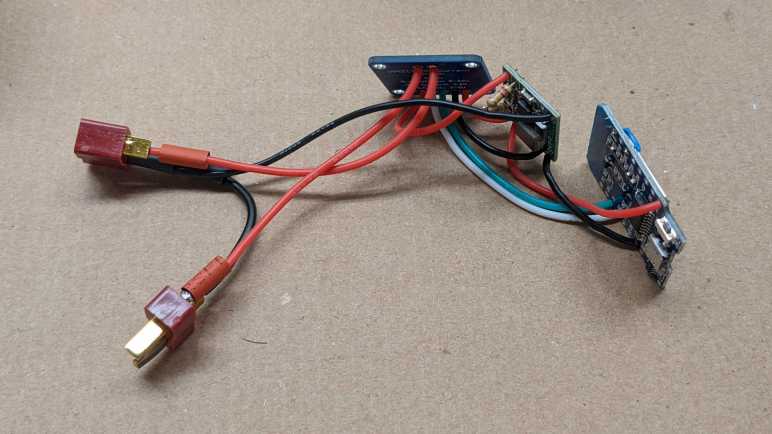

I think I’ve got the hardware portions of my solar power monitor sensor node figured out, so I can write the first version of corresponding software logic. I have set out the following requirements:

- Over-discharge protection: If battery voltage drops below a threshold, put the system to sleep to protect the battery.

- Low solar output: When the solar panel isn’t generating any power, put the system to sleep.

- Battery charging start: when panel power generation rises above a certain level for the first time that day, start charging the repurposed USB power bank battery.

- Battery charging pause: If cloud cover causes a dip in solar power, pause charging.

- Battery charging stop: Once battery cell voltage rises to a certain level, stop charging.

- Sleep override: local hardware method to prevent deep sleep.

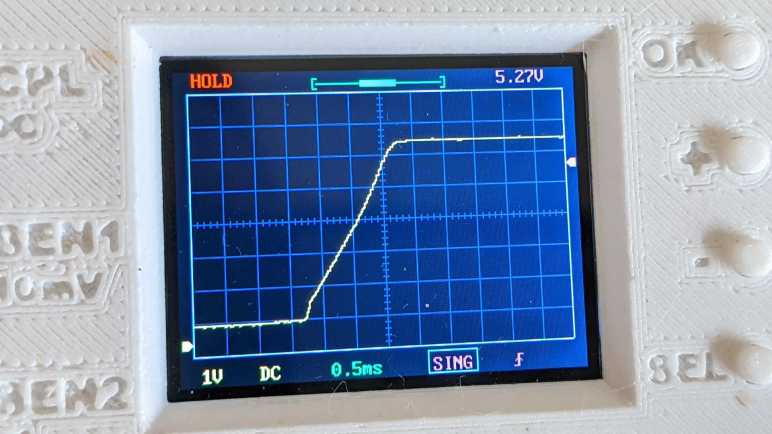

The ESPHome documentation for deep sleep described one way to prevent sleep using MQTT, keeping a node awake to receive firmware updates. But I wanted something even lower level hence the jumper and it became useful when I implemented the “low solar output, go to sleep” logic. Apparently INA219 component’s first power value always return zero. Which meant as soon as it booted up, that initial zero reading puts the node immediately back to sleep before it would even get on the network. (Never mind checking MQTT!) The solution is to switch from sampling values once a minute to sampling once a second, and make decisions based on average over a minute.

A different approach would be to go to sleep based on sun’s position in the sky, which can be queried and used in the Sun component. However, I expect this component has dependency on network connection (it needs to know the time, for starters) and would not be reliable if the network goes down. It also doesn’t know if the sun is obscured by clouds, so I think it’s better to use panel power output to decide what to do during the day. But I may explore using the Sun component in a future version to sleep all through the night instead of waking up every few minutes to fruitlessly check power level.

Strictly speaking, I don’t need to worry about stopping battery charging. I can supply 5V all day when panel delivers power, and trust the USB power bank charging circuit to keep the battery from being overcharged. But keeping lithium-ion cells full would shorten their useful life, so in the interest of battery longevity I’ll stop charging before full. On that topic: for optimal battery life I should charge it slowly over the course of the day, but I don’t have control over charging rate used by USB power bank.

One thing I don’t know yet is how the system will handle several rainy days in a row. I assume this panel can still generate enough power to charge an 18650 battery cell, but I might be wrong! I’ll have to wait for a long stretch of rain to come to Southern California, which may be a long wait. After seeing its behavior I can adjust for a future version.

Here’s version 1 of my ESPHome configuration YAML, and I expect to fine tune various hard-coded threshold values over the weeks ahead while I build more projects:

# Blue LED on the ESP8266 module signals connection status.

status_led:

pin:

number: 2

inverted: true

# The goal is to charge once a day, and this flag tracks if we've already done it.

globals:

- id: never_charged_today

type: bool

restore_value: no

initial_value: "true"

# We can go to deep sleep to conserve battery, but sometimes we don't want to

# actually go to sleep. For example, when we need to upload a firmware update.

# Pin 13 is an input pin with internal pullup. It should be wired to a jumper

# that would ground the pin if jumper is present. Removing the jumper should

# disable going to deep sleep. To enforce this, call try_to_sleep script

# instead of calling deep_sleep.enter directly.

deep_sleep:

id: deep_sleep_1

binary_sensor:

- platform: gpio

name: "Disable Sleep"

id: sleep_jumper

pin:

number: 13

mode:

input: true

pullup: true

on_release:

then:

- logger.log: "Sleep jumper installed"

- script.execute: try_to_sleep

script:

- id: try_to_sleep

then:

if:

condition:

binary_sensor.is_on: sleep_jumper

then:

logger.log: "Sleep requested but staying awake due to override jumper"

else:

- logger.log: "Sleep requested and permitted by jumper"

- delay: 5s # Allow sensor values to be sent.

- deep_sleep.enter:

id: deep_sleep_1

sleep_duration: 10min

# This should be wired to a 1k resistor, which then connects to the enable pin

# of a power supply source. When ON, it should deliver power to charge the battery.

switch:

- platform: gpio

pin: D5

id: charge_switch

name: "Charge Battery"

restore_mode: RESTORE_DEFAULT_OFF

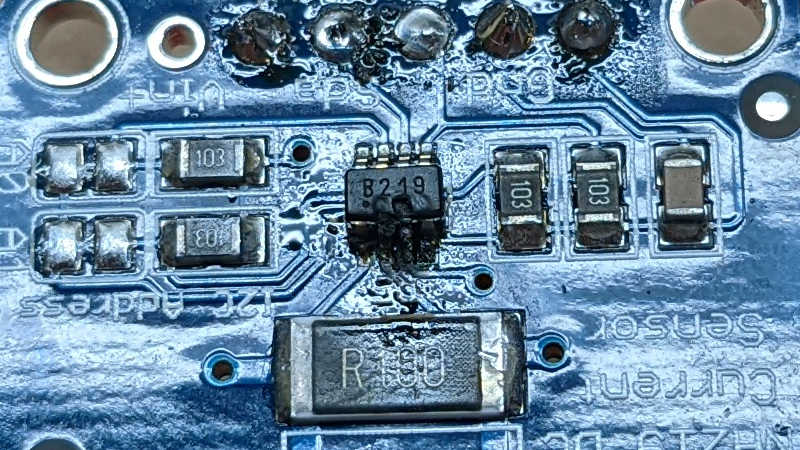

# An I2C INA219 sensor monitors panel voltage, current, and calculates power.

i2c:

sda: 4

scl: 5

sensor:

- platform: ina219

address: 0x40

shunt_resistance: 0.1 ohm

max_voltage: 24.0V

max_current: 3.2A

update_interval: 1s

current:

name: "Panel Current"

id: solar_panel_current

accuracy_decimals: 5

filters:

sliding_window_moving_average:

window_size: 90

send_every: 60

send_first_at: 15

power:

name: "Panel Power"

id: solar_panel_power

accuracy_decimals: 5

filters:

sliding_window_moving_average:

window_size: 90

send_every: 60

send_first_at: 15

on_value:

then:

# When power is low, put the board to sleep.

# Note: upon boot, the first reading of current (and therefore power) always

# seems to be zero, so we need to run moving average filters to ensure we

# don't shut off immediately on power-up.

if:

condition:

and:

- sensor.in_range:

id: solar_panel_power

below: 0.01

- sensor.in_range:

id: solar_panel_voltage

below: 3.0

then:

- logger.log: "Panel delivering low power, should go to sleep"

- globals.set:

id: never_charged_today

value: "true"

- script.execute: try_to_sleep

bus_voltage:

name: "Panel Voltage"

id: solar_panel_voltage

accuracy_decimals: 5

filters:

sliding_window_moving_average:

window_size: 90

send_every: 60

send_first_at: 15

# ESP8266 ADC pin should be wired to a resistor just over 100kOhm to measure

# lithium-ion battery cell voltage. Values under calibrate_linear need to be

# customized for each board (and their resistors.)

- platform: adc

pin: A0

name: "Battery Voltage"

id: battery_voltage

update_interval: 1s

accuracy_decimals: 3

filters:

- calibrate_linear:

- 0.84052 -> 3.492

- 0.99707 -> 4.113

- sliding_window_moving_average:

window_size: 90

send_every: 60

send_first_at: 15

on_value:

then:

- if:

condition:

and:

- lambda: "return id(never_charged_today);"

- sensor.in_range:

id: solar_panel_power

above: 10

then:

- logger.log: "Panel has power, start charging for the day"

- globals.set:

id: never_charged_today

value: "false"

- switch.turn_on: charge_switch

- if:

condition:

and:

- switch.is_on: charge_switch

- sensor.in_range:

id: solar_panel_power

below: 5

then:

- logger.log: "Charging paused due to low panel output"

- globals.set:

id: never_charged_today

value: "true" # Resume charging if power returns

- switch.turn_off: charge_switch

# When battery is low enough to trigger this emergency measure, we

# would not be able to activate charging ourselves. Charging needs to

# be activated manually (or at least externally)

- if:

condition:

sensor.in_range:

id: battery_voltage

below: 3.0

then:

- logger.log: "Battery critically low, should sleep to protect battery."

- script.execute: try_to_sleep

# We don't need a full charge to last through a day, so turn off charging

# well before reaching maximum in order to improve battery longevity

on_value_range:

above: 4.0

then:

- logger.log: "Battery charge is sufficient"

- switch.turn_off: charge_switch