I tried to revive a FormLabs Form 1+ resin printer that had been sitting unused for years, but the test print was a failure. Comparing against videos on YouTube showing a Form 1/1+ in action, I noticed two differences. First, the resin vat tilting action (to peel it off a print between layers) was not happening. And more seriously, the laser beam was not moving around to trace out the shape. Instead, it stayed focused on one spot solidifying resin and damaging the resin vat at that point. There are four mechanical actuators on this device: the vat tilt stepper motor, X/Y-axis galvanometers (shortened below to galvos), and the Z-axis stepper motor. Out of four, three aren’t working! Quite disappointing, but at least they should be electromechanical issues that I have a better chance of fixing than software issues. I’ll take it apart and look around.

My disassembly was guided by Bunny Studios’ Form 1 teardown blog post from almost ten years ago. I was glad for the reference, but as the blog post pointed out, FormLabs designed the machine for easy disassembly, inspection, and repair. All fasteners are easily accessible and use the same 2.5mm hex key.

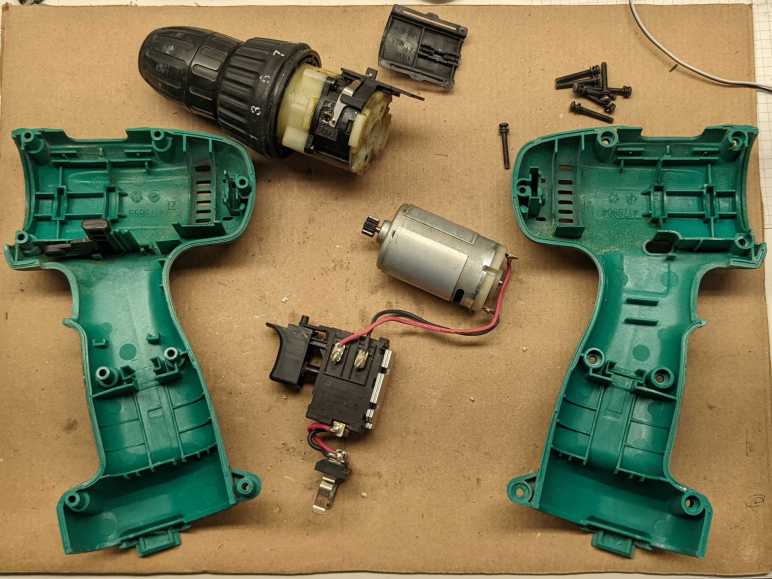

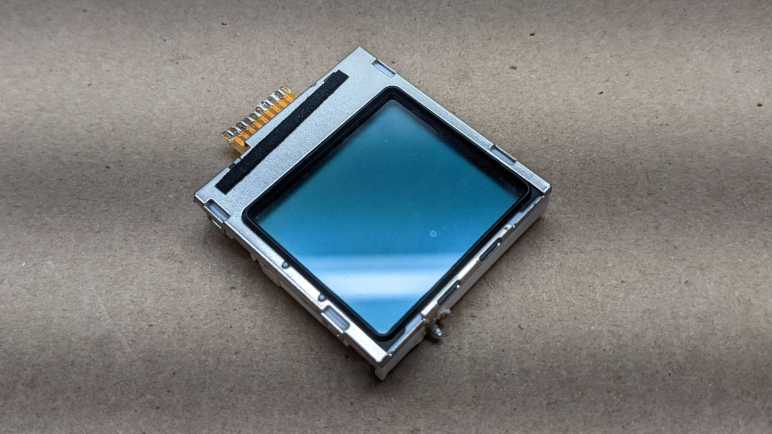

Once I got to remove the back panel, majority of control circuitry became accessible. Only one circuit board is not visible in this picture, as it is mounted in the front for power button and screen.

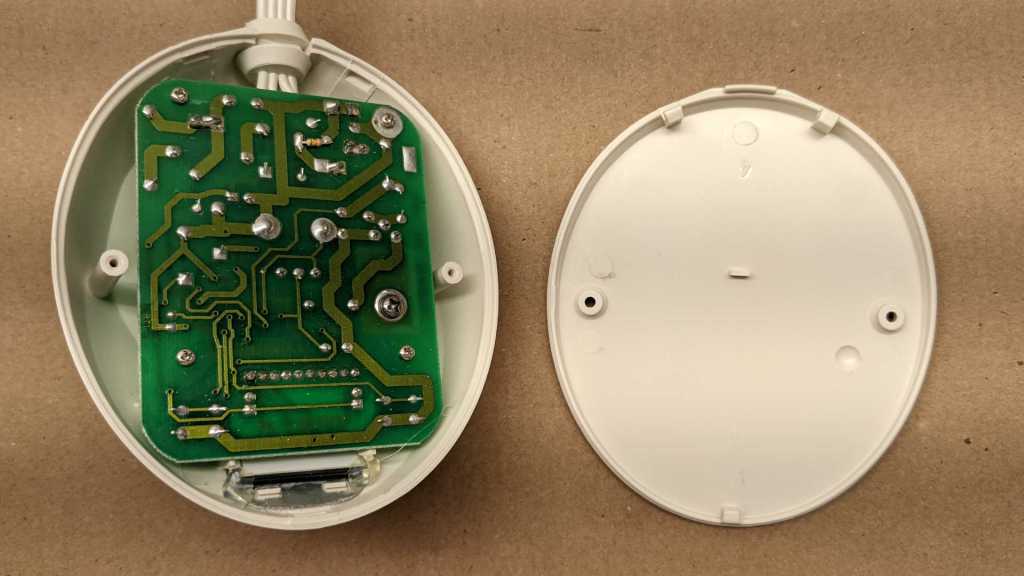

The large horizontal circuit board has a power-handling section to the right, as indicated by the presence of many transistors, diodes, and inductors. To the left is the brain, including a SanDisk 4GB SD card that wasn’t accessible until the back panel was removed. The smaller vertical circuit board on the right is dedicated to X/Y position control, judging by cables connecting it to the X/Y galvos.

This printer had been shipped around without its original packaging materials, so I had hoped the problem was as easy as a loose connector I could plug back in. Thus my attention was immediately drawn to headers on these circuit board without a wire, but there were no candidate loose wires to plug into those headers. Apparently FormLabs has intentionally chosen not to use those connections, likely related to changes from original Form 1 to this Form 1+.

One of the unused connectors was labeled GALVO Y POWER. I see cables on GALVO Y SIGNAL and GALVO X SIGNAL as well as GALVO X POWER. I guess both galvos are powered from GALVO X POWER cable. This might be relevant to what I find later.

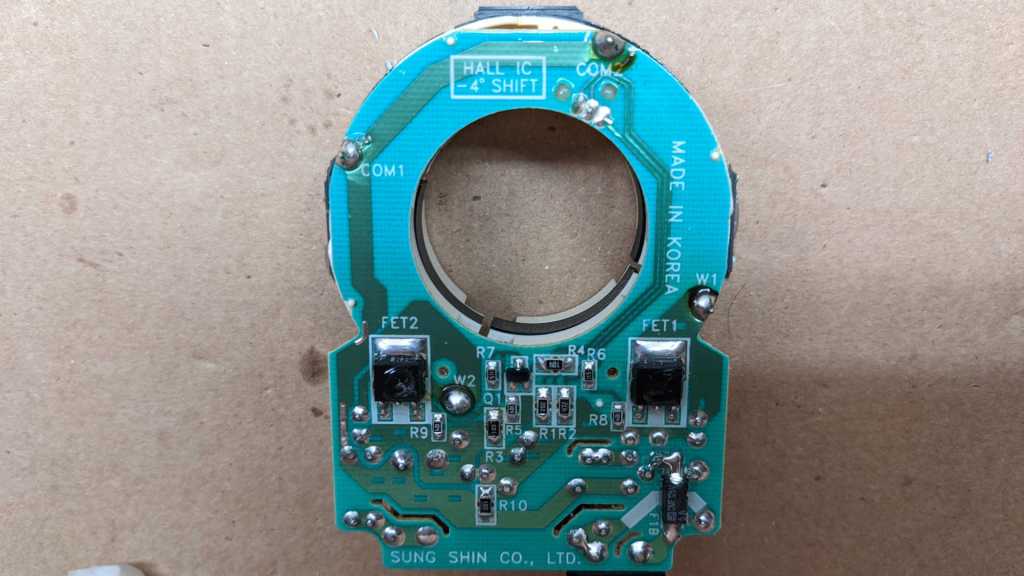

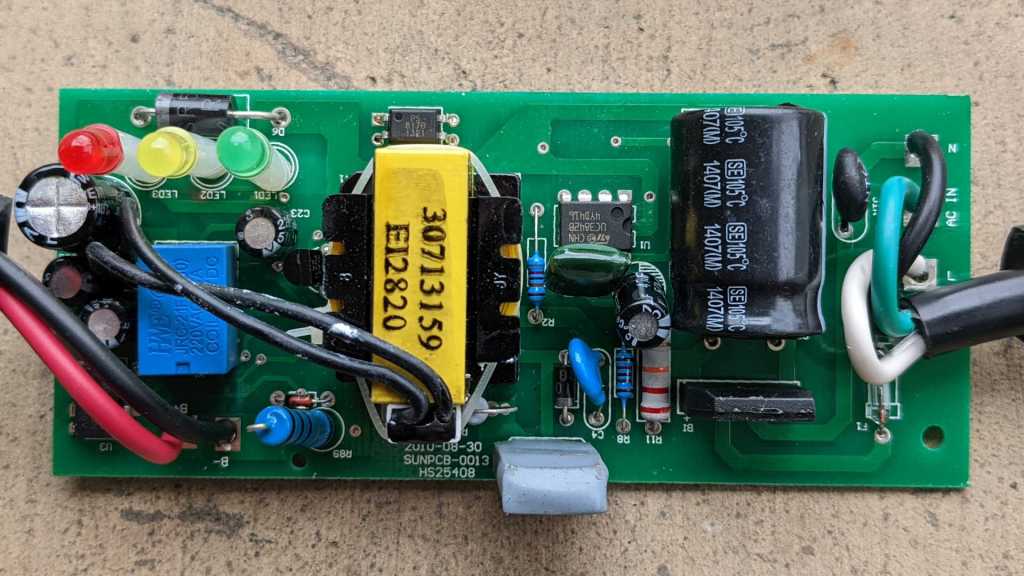

Disappointed that I didn’t find a loose connector I could plug back in or any other obvious easy-to-fix problems, I proceeded to unplug and reinstall every connector to reseat them. Working from left-to-right, everything looked and felt fine until I unplugged the right-most galvo connector. Once it was removed, I got a clear view of the galvo power connector below it.

Discoloration from overheating and possibly soot from a small fire. The toasty connector is the other end of GALVO X POWER. I don’t know enough about this device to say sharing X and Y galvo power from a single connector caused the failure, but it certainly looks suspicious.

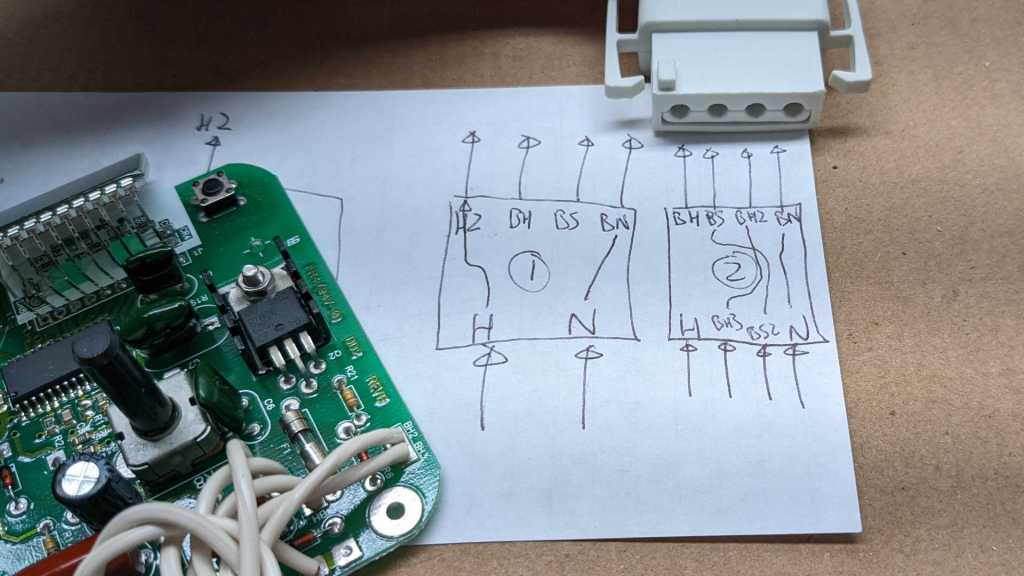

I saw no obvious places where GALVO Y POWER could have connected to this galvo control board. I guess it is a later revision that integrated both galvo controls on a single board powered by a single cable. Compare this to Bunny’s earlier device, where we see two separate and seemingly identical galvo control boards, one for X and one for Y, each with their own power and signal cables.

This device is long out of warranty, and official support ended in 2017. I don’t expect FormLabs to have a replacement galvo control board for this Form 1+, but it wouldn’t hurt to ask and see what they say.