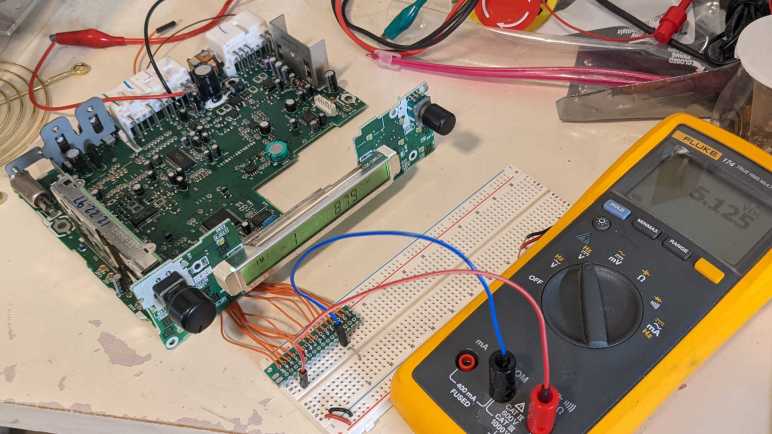

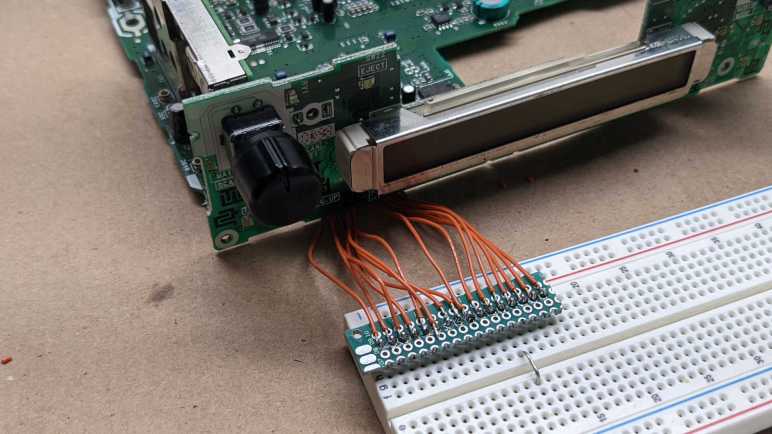

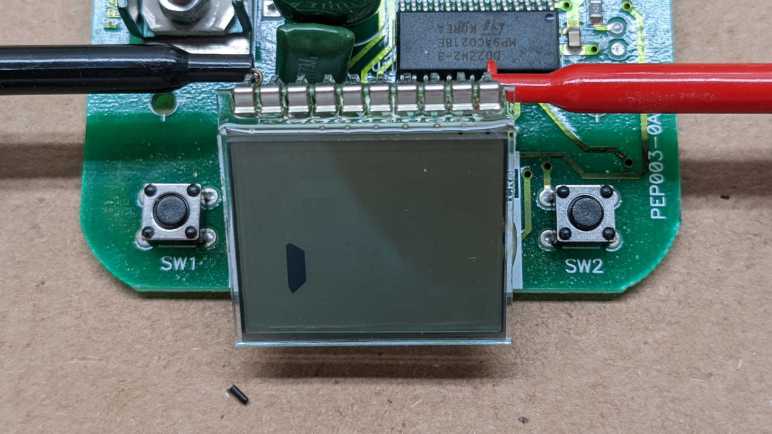

I’m working to understand how to control the LCD on the handset of an AT&T CL84209 landline phone system, and I started by observing the behavior of its eight IO pins (plus one pin already established to be ground) using the analog mode of my Saleae Logic 8 analyzer. Two pins were immediate candidates for a serial data pin and its corresponding clock pin, so I switched my analyzer to digital mode observing those two pins specifically.

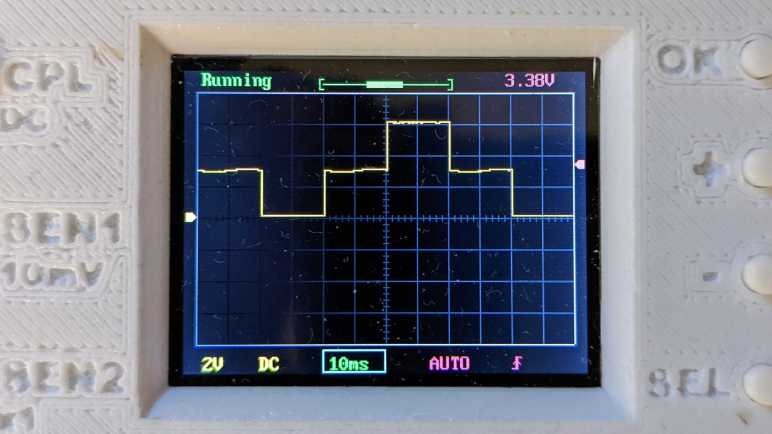

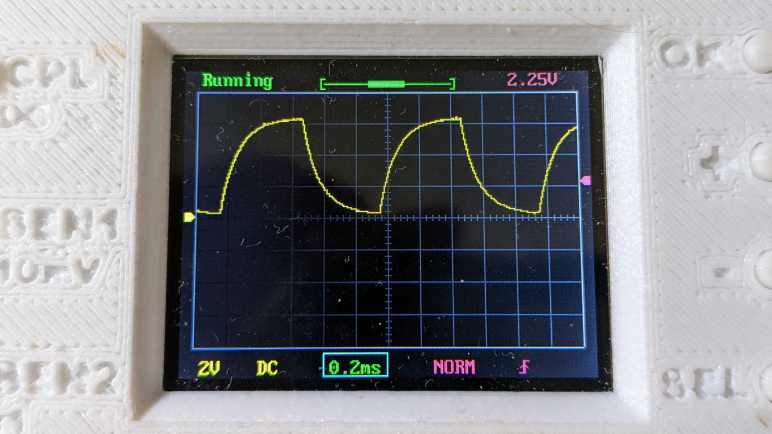

Mouse hovering over the clock line, the analyzer software told me it started at a frequency of 7.2kHz and then sped up to 100kHz during the startup sequence. 100kHz is very promising, because it matches “Standard Mode” speed of I2C. The previous LCD controller I played with used a proprietary Sanyo protocol called CCB, but I’m hopeful this unknown chip uses Philips I2C. So in the spirit of “be sure to check the easy thing first” I activated I2C protocol analyzer built in to Saleae’s software. This presented a stream of decoded bytes and no sign of error.

Good news: it is indeed I2C!

Bad news: within less than ten seconds of powerup, there are 2569 captured and decoded messages. That is a lot of raw data to wade through when I don’t datasheets to make sense of it all. But the situation isn’t quite as bad as it initially looked. While I’ve tapped pins directly connected to the LCD, that doesn’t mean all the data we see on those lines are relevant. I2C is a data bus for multiple devices to communicate, and I see multiple addresses listed in the I2C decoder output.

I wanted to filter messages by address, but I failed to find such an option in Saleae software. Instead, I copied the data output into a Jupyter notebook and wrote a bit of quick-and-dirty Python to parse them. There were ten unique I2C addresses in this output:

{'0x52', '0x51', '0x50', '0x56', '0x3E', '0x53', '0x54', '0x55', '0x4B', '0x57'}Scrolling through the decoder output, traffic to address 0x3E stood out because they were the longest. Many of these I2C messages had only one or two bytes, but some messages to 0x3E were much longer. The long messages have a pattern, they come in sets of three: two 18-byte messages followed by one with 19 bytes.

write to 0x3E ack data: 0x80 0x81 0x40 0x20 0x43 0x4F 0x4E 0x4E 0x45 0x43 0x54 0x49 0x4E 0x47 0x2E 0x2E 0x2E 0x20

write to 0x3E ack data: 0x80 0xC1 0x40 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20 0x20

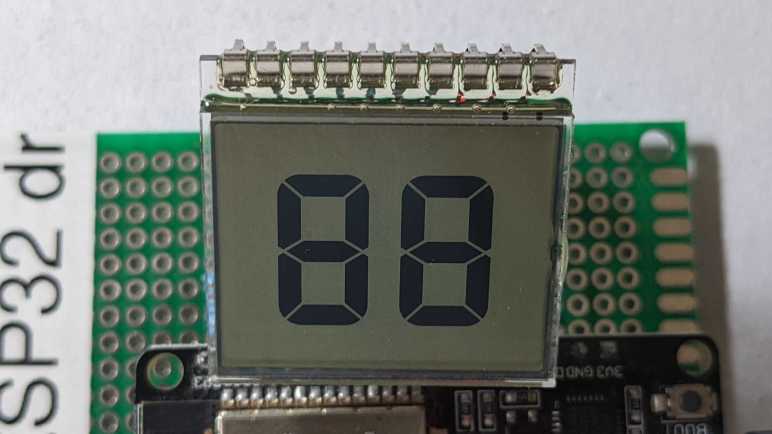

write to 0x3E ack data: 0x80 0x40 0x40 0x00 0x00 0x10 0x02 0x01 0x04 0x00 0x10 0x00 0x04 0x01 0x00 0x02 0x10 0x04 0x00 These messages won’t have enough bits to control individual dots on the dot-matrix display. However, they might contain alphanumeric data for the LCD controller to use a font lookup table. Again, in the spirit of trying the easy thing first, I compared the first line of data against an ASCII chart.

| 0x80 | 0x81 | 0x40 | 0x20 | 0x43 | 0x4F | 0x4E | 0x4E | 0x45 | 0x43 | 0x54 | 0x49 | ox4E | 0x47 | 0x2E | 0x2E | ox2E | 0x20 |

| [?] | [?] | @ | [space] | C | O | N | N | E | C | T | I | N | G | . | . | . | [space] |

“CONNECTING…” is the first line displayed on the LCD! We have a winner, time to dig into traffic addressed 0x3E for this I2C LCD.