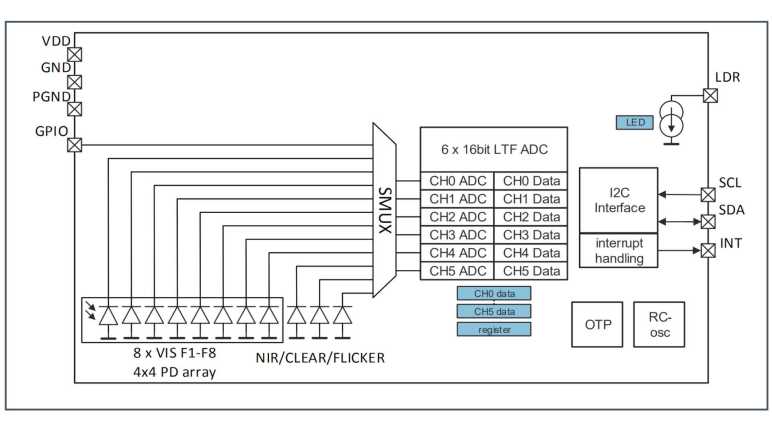

Looks like I will never learn how to build custom configurations for AS7341 SMUX, but at least I have presets I could copy/paste and that’s good enough for my hobbyist level project. The goal is to convert I2C communication from Arduino’s standard Wire library to the twi_nonblock library bundled as part of Mozzi library. Arduino Wire library would block execution while I2C communication is ongoing, which causes audible glitches with Mozzi sketches. Converting to twi_nonblock avoids that issue.

Using Adafruit’s AS7341 Arduino library and sample sketches as my guide, it was relatively straightforward to converting initialization routines. Partly because most of them were single-register writes, but mostly because non-blocking isn’t a big concern for setup. I could get away with some blocking operations which also verified I2C hardware was working before adding the variable of nonblocking behavior into the mix.

To replicate Adafruit’s readAllChannels() behavior in a nonblocking manner, I split the task into three levels of state machines to track asynchronous actions:

- Lowest level state machine tracks a single I2C read operation. Write the address, start a read, and copy the results.

- Mid level state machine pulls data from all 6 AS7341 ADC. This means setting up SMUX to one of two presets then waiting for that to complete. Start sensor integration, then wait for that to complete. And finally copy sensor results. Each read operation is delegated to the lower level state machine.

- High level state machine runs the mid-level state machine twice, once for each SMUX preset configuration.

Once that high level state machine runs through both SMUX preset configurations, we have data from 10 spectral sensors. The flicker detector is the 11th sensor and not used here. This replicates the results of Adafruit’s readAllChannels() without its blocking behavior. Getting there required an implementation which is significantly different. (I don’t think I copied any Adafruit code.)

While putting this project together, my test just printed all ten sensor values out to serial console. In order to make things a little more interesting, I brought this back full circle and emulated the behavior of Emily Velasco’s color organ experiment. Or at least, an earlier version of it that played a single note depending on which sensor had returned highest count. (Emily has since experimented with vibrato and chords.) I added a lot of comments my version of the experiment hopefully making it suitable as a learning example. As a “Thank You” to Emily for introducing me to the AS7341, I packaged this project into a pull request on her color organ repository, which she accepted and merged.

This is not the end of the story. twi_nonblock supports only AVR-based Arduino boards like the ATmega328P-based Arduino Nano I used for this project. What about processors at the heart of other Arduino-compatible boards like the ESP32? They can’t use twi_nonblock and would have to do something else for glitch-free Mozzi audio. That’ll be a separate challenge to tackle.

Code for this project is publicly available on GitHub.