Taking a break from exploring electronics, I went to the to-do list and picked off the item “look into generative AI”. This particular story started several years ago when GitHub user @johndpope opened a GitHub issue on my Sawppy repository advocating for a Lexan body shell. Aesthetics is not my focus for Sawppy but I’m glad to see others are thinking about cosmetic enhancements. In a recent update, @johndpope added a large number of images generated by Stable Diffusion. They’re really… something. If there’s potential here, I really have to squint to see them. For the most part these images generated by Stable Diffusion were not mechanically sound. Or even mechanically feasible. Or even sane. It’s a patchwork of bits I recognize, assembled into a surrealistic dream that reminds me of Salvador Dali paintings.

(Image credit: Stable Diffusion from @johndpope prompt)

What’s going on here? An Ars Technica article about Stable Diffusion running on Apple Silicon had put a note in the back of my mind, and after seeing @johndpope updates I thought I would look into it further. I do own an Apple MacBook Air with a M1 Apple Silicon processor appropriate for the links in that Ars Technica article, but it is my understanding my gaming PC’s NVIDIA RTX 2070 GPU would be faster still. So I followed instructions on this @AUTOMATIC1111 GitHub repository to run Stable Diffusion locally on my machine.

My experiment results were no better than what @johndpope had posted. Jumbles of things, nothing very coherent, and the occasional misshapen nightmare fuel. Other tools like Midjourney and OpenAI’s DALL-E were supposed to be better, but they were commercial offerings not available for running locally and I didn’t feel like this experiment was worth handing over my credit card. Then I read Microsoft had licensed DALL-E for Bing Image Creator. No credit card necessary, just a Microsoft account. Well, I have that!

To see if things have gotten better, I headed over and here’s the most sane result from the prompt: “mechanical diagram of a six-wheel mars rover in blueprint style“

(Image credit: Bing Image Creator from my prompt)

This is better looking than what I got out of local Stable Diffusion. (And ironically less Dali-like, given the DALL-E name.) But it is clearly weak on sound mechanical design concepts starting with the fact I asked for six wheels and got only four. Symmetry is not a well understood concept, either, as these four wheels are visibly misaligned relative to each other along orthographic axes. And there are random parts scattered around, what’s up with that? And finally, it seemed to have ignored the “Mars” part of my prompt as this creation shows no indication of adaptations for a Martian operating environment.

I tried a few variations on my prompt and my impression of this tool is to lean into its tendency for mechanical nonsense and get designs packed with greeble, because it’s certainly got plenty of visual noise. But I certainly can’t use it for anything that can function mechanically. To be fair, mechanical design is not the focus of such image generators. Plus, this field is still evolving rapidly so in a few months things might be very different. But at least for today, image generation AI pose no threat to mechanical engineering jobs.

A short while later I got another idea: instead of trying to make it do something mechanical, how about an abstract cartoon rover mascot?

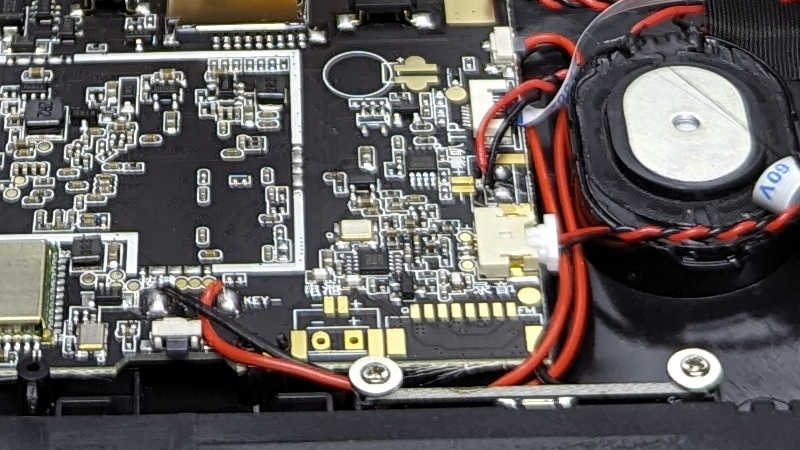

[UPDATE]: In the comments, Quinn Morley got an interesting looking rover from the prompt “SAWPPY the rover, with six wheels and a body made of glass instead of metal, on Mars.“

(Image credit: Bing Image Creator from Quinn Morley’s prompt)

At first glance, this looks really good!

But upon closer inspection, I noticed the suspension linkages are attached to tires instead of hubs, and there seem to be only five wheels instead of the six specified. Something about this particular combination of flaws is appealing to DALL-E’s inscrutable brain because it also showed up in my cartoon mascot experiment.