About a month ago Mars rover Curiosity’s computer system had a hiccup and reset itself, causing its management team here on Earth to switch to its alternate computer. These two computers – referred to as Side-A and Side-B, allow Curiosity to run on one while mission team diagnoses the other. Initial reports indicate a problem with Curiosity computer’s on board data storage systems.

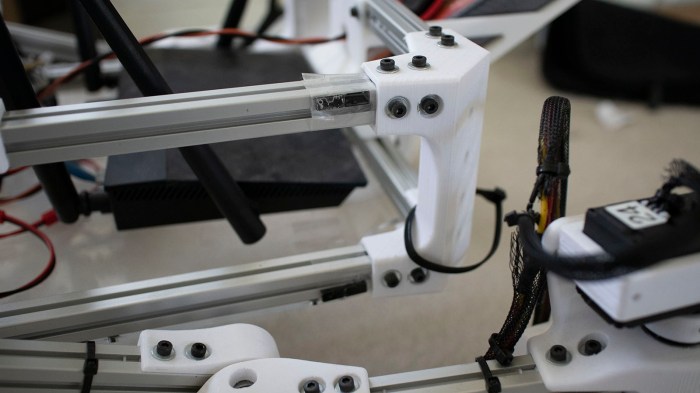

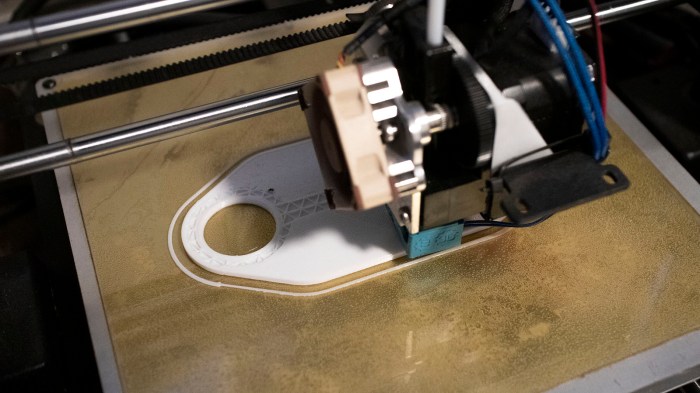

My rover Sawppy is modeled after Curiosity, and it’s only be a matter of time before Sawppy emulates its big brother with a data storage problem too – the microSD card on a Raspberry Pi 3 computer is a notorious point of failure. But Sawppy doesn’t have a redundant computer system on board that can be switched remotely. Since I’m typically not far away, I can walk up to my rover and perform replacement manually.

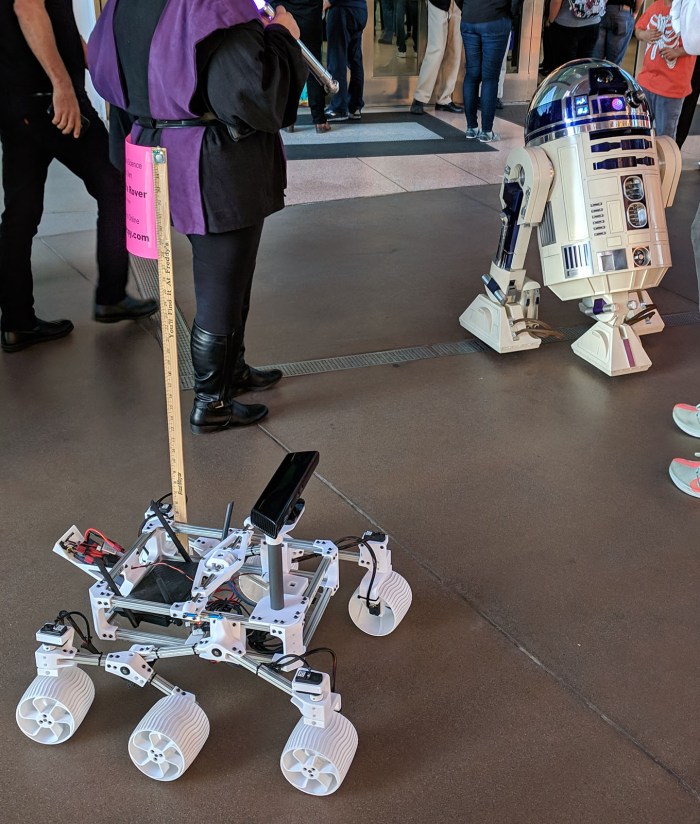

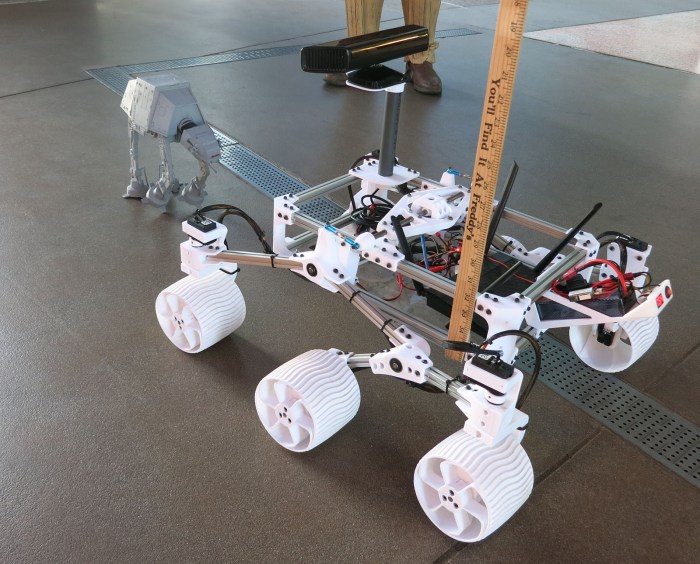

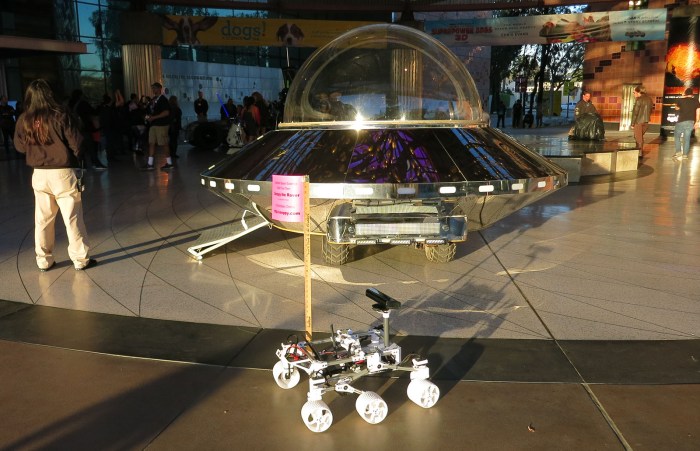

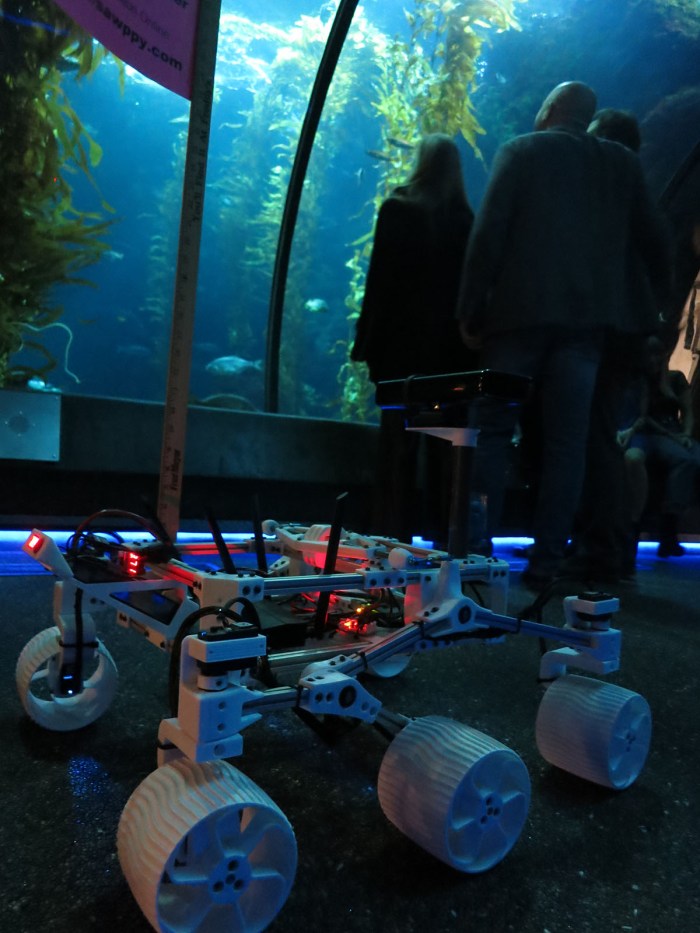

But I could only walk up and replace it if I had a replacement handy! This is growing in importance as Sawppy started getting booked for public appearances. When it’s just a hobbyist project it’s not a big deal if Sawppy encounters a problem, I just pack it up until I can get home to my workbench. But if we’re starting to get into situations where Sawppy is actually a featured item, we need to know how to make sure The Show Must Go On.

Thus the latest addition to Sawppy’s field repair (“first aid”) kit: Highest priority is a copy of Sawppy’s microSD card already configured with all necessary software. A microSD card is very small and light, so there’s no excuse not to have one always on hand.

Lower priority, for times when there’s space to spare, is a backup Raspberry Pi 3.

And lowest priority is a LewanSoul servo USB to half-duplex translation board required to operate LewanSoul servos. And while I’m at it, pack a replacement servo as well!

Now that I have some idea of what happens inside

Now that I have some idea of what happens inside