The people at Robotis who created TurtleBot 3 created a pretty good online manual for their robot that also served as a decent guide for a beginner like myself to start experimenting with ROS. But that’s not the only resource they’re released to the public – they’ve also applied themselves to writing a book. It has a straightforward title “ROS Robot Programming” and is described to be a compilation of what they’ve learned on their journey to create the TurtleBot 3. Pointers to the book are sprinkled throughout the TurtleBot 3 manual, most explicitly under the “Learn” section with additional resources.

The people at Robotis who created TurtleBot 3 created a pretty good online manual for their robot that also served as a decent guide for a beginner like myself to start experimenting with ROS. But that’s not the only resource they’re released to the public – they’ve also applied themselves to writing a book. It has a straightforward title “ROS Robot Programming” and is described to be a compilation of what they’ve learned on their journey to create the TurtleBot 3. Pointers to the book are sprinkled throughout the TurtleBot 3 manual, most explicitly under the “Learn” section with additional resources.

The book is available in four languages: English, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. The English and Chinese editions are also available freely as PDF. I thought I’d invest some time into reading the book, here are my comments:

Chapters 1-7: ROS Fundmentals

The reader is assumed to be a computer user who is familiar with general programming concepts, but no robotics knowledge is assumed. The book starts with the basic ideas behind ROS, then working from there. These chapters have a great deal of overlap with existing “Beginner Level” tutorials on ROS Wiki. Given this, I believe the bigger value of this book is in its non-English editions. Chinese/Japanese/Korean readers would probably benefit more from these sections written in their respective languages, making this information accessible for readers who can’t just go to the English ROS Wiki tutorials like I did.

Content-wise, the biggest deviation I found in this book was that it treated the action library as peers of ROS topics and services. As a user I agree it made sense to cover them together and I’m glad this book did it. And as someone who has worked on programming platforms, I understand why the official documentation treated them differently.

Chapter 8: Sensors and Motors

Given that chapters 1-7 overlapped a lot with the tutorials I’ve already covered, it was not terribly informative. That changed when I got into chapter 8, where we started talking about a few different classes of sensors people have used in ROS. When it came to motors, though, the only one covered was Robotis’ own Dynamixel product. This was a little disappointing – they could have at least put some minor lip service to motors other than their own product. But they chose not to.

This chapter ended with a useful tutorial and some words of wisdom about how to navigate the big library of ROS modules openly available for us to play with. This is a good place for the topic, because sensor and motor driver libraries are going to be the first things beginners have to deal with beyond core ROS modules. And skills dealing with these libraries will be useful for other things beyond sensors and motors.

Chapter 9-13: All Robotis All The Time

The rest of the book is effectively an extension of the TurtleBot 3 manual with side trips to other Robotis projects. They go over many of the same ideas, using their robots as example. But while the manual focused on a specific robot, the book did try to go a little deeper. They said their goal is to cover enough so the reader can adapt the same general ideas to other robots, but I don’t feel I’ve received quite enough information. This is only a gut feeling – I won’t know for sure until I start rolling up my sleeves and get to work on a real robot.

The final few chapters felt rushed. Especially the abrupt ending of the final manipulator chapter. Perhaps they will work to fill in some of the gaps in a future edition.

Final Verdict: B+

I felt like my time spent reading the PDF was well spent. If nothing else, I have a much better understanding of how TurtleBot 3 (and friends) work. The most valuable aspect was seeing ROS described from a different perspective. I plan to check out a few other ROS books from the library in the future, and after I get a few books under my belt I’ll have a better idea how “ROS Robot Programming” ranks among them. It’s clear the first edition has room for improvement, but it is still useful.

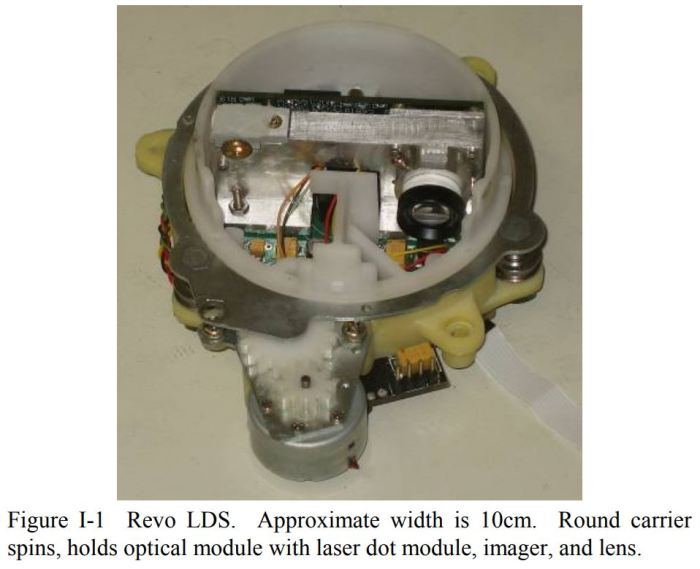

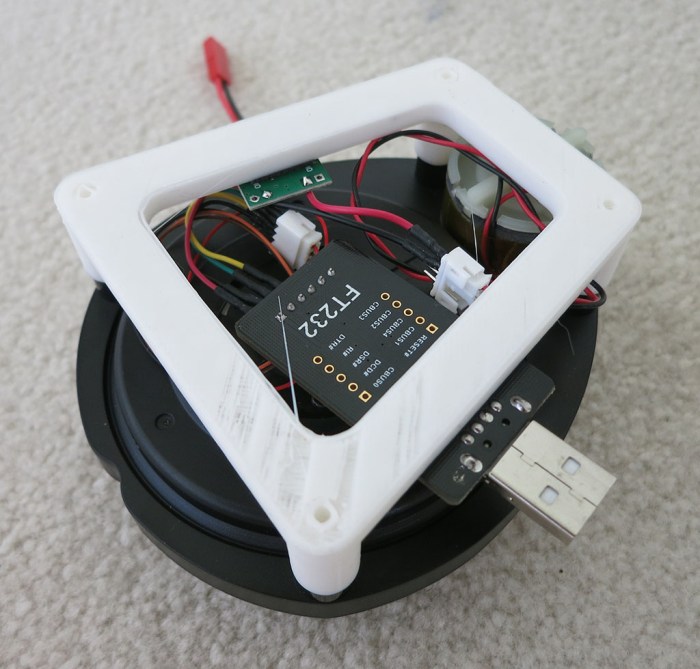

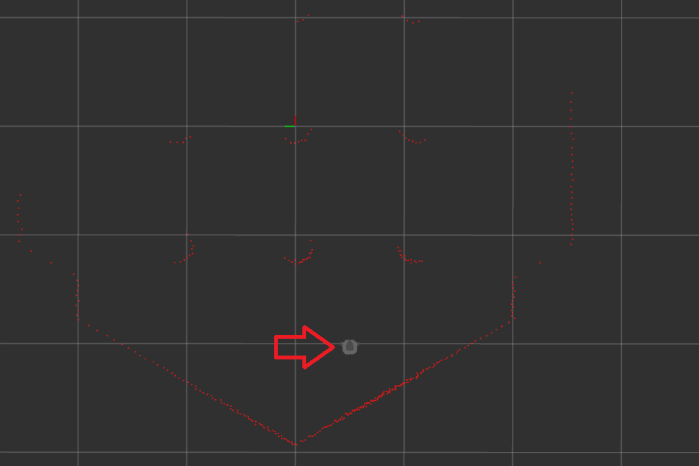

I bought a laser scanner salvaged from a Neato robot vacuum

I bought a laser scanner salvaged from a Neato robot vacuum

The low-end option is the “

The low-end option is the “ The higher-end option is the “

The higher-end option is the “

While we’re on the topic of things I wanted to investigate in the future… there was a recent announcement declaring availability of

While we’re on the topic of things I wanted to investigate in the future… there was a recent announcement declaring availability of  Being on the leading edge carries its own kind of thrill. When I started looking over the TurtleBot 3 manual I noticed the index listed a “

Being on the leading edge carries its own kind of thrill. When I started looking over the TurtleBot 3 manual I noticed the index listed a “

After realizing my beginner’s mistake of

After realizing my beginner’s mistake of