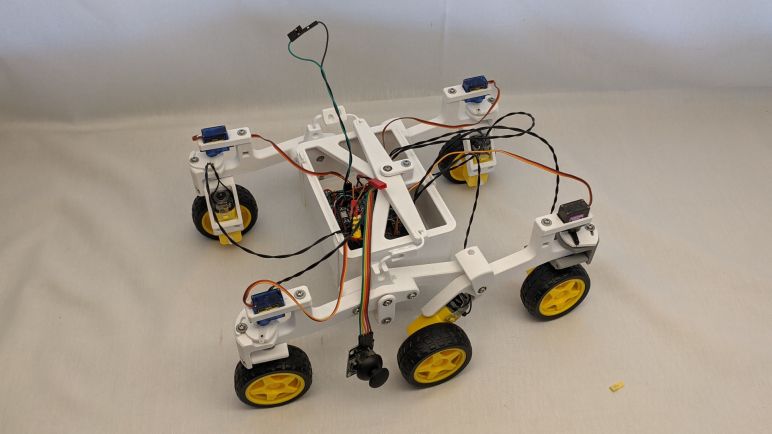

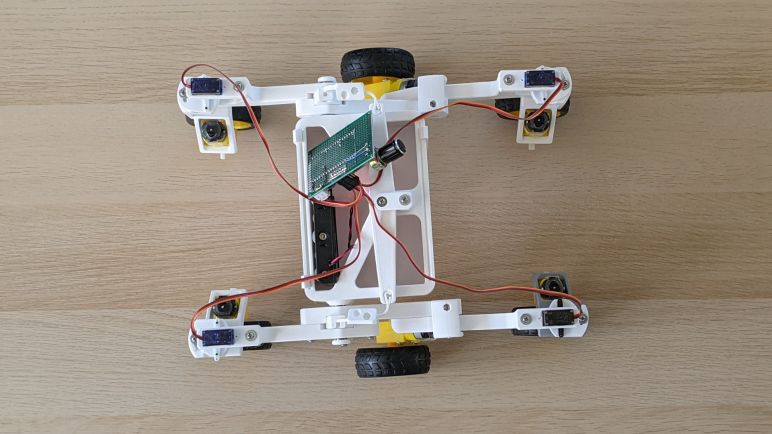

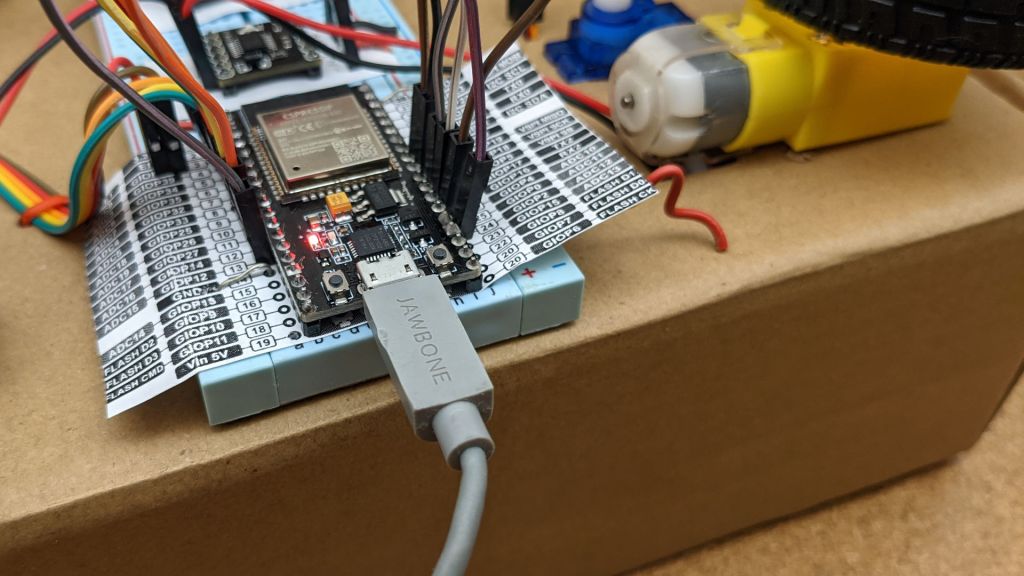

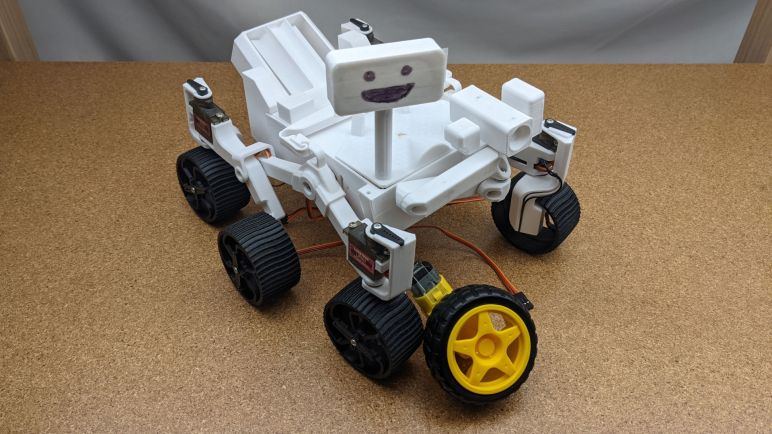

I have a Spektrum DX3E transmitter designed for radio control ground vehicles, with a matching Spektrum SR300 receiver for mounting on the vehicle. I want radio control equipment like this to be one of many options for controlling a Micro Sawppy rover, and my DX3E will be my example RC equipment for developing corresponding ESP32 software. Before I dive into the software, though, there is a minor hardware modification I wanted to make.

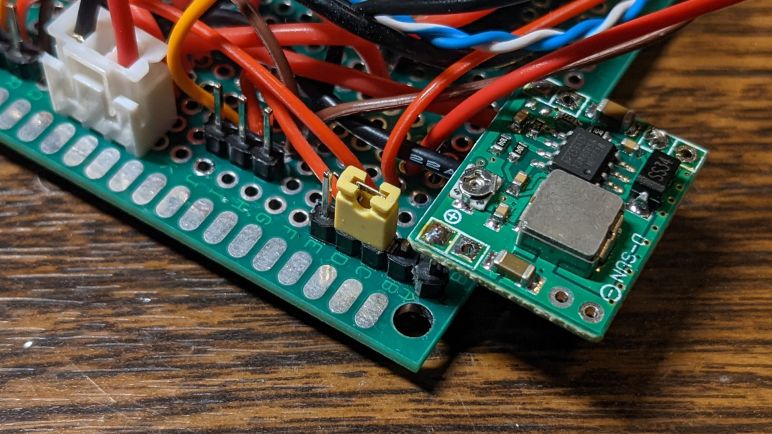

There are several conventions for radio control servo plugs, which look superficially similar to generic 0.1″ pitch wire connectors but aren’t quite identical. From my past experience I knew of the “Futaba” style, with a tab to help with proper alignment. I didn’t have many of those on my radio control toys. Most of my old equipment conformed to the “JR” style, which lack the tab but have tiny bevels to prevent plugging a servo into the receiver backwards. Commodity micro servo plugs do not have this bevel, and neither will Micro Sawppy ESP32 plug. While it is theoretically possible to manually cut the necessary bevel in a generic 0.1″ pitch three-position connector, I have several connectors in mind for experimentation and that would quickly get tedious. So for my own experimentation purposes, I decided to cut off the wedges that enforce bevel direction on the receiver instead. This is not necessarily something I recommend for others. If they only have a single device, it’ll probably be better to cut bevels.

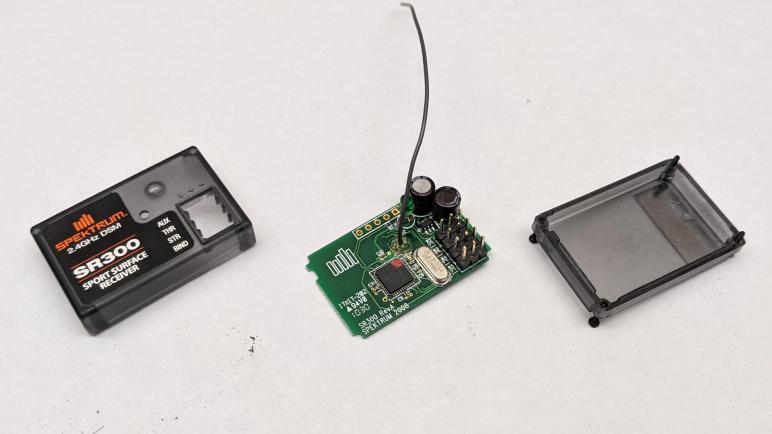

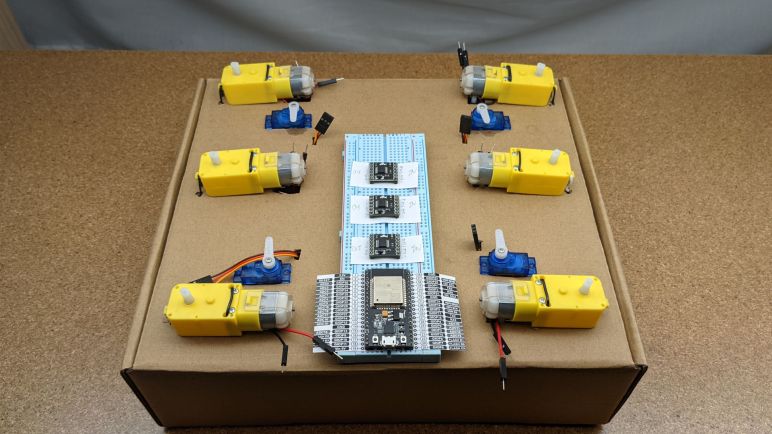

I didn’t want to cut off those wedges with with the receiver intact, because a slip of the blade might damage its circuit board. So I’ll take it apart, which gives me a chance to look inside as well, something I always enjoy. There were no elaborate security measures, merely four small Philips head screws. Once they were removed, the case comes apart easily. In my case, a few grams of dirt fell out as well. Results of my RC cars going off track due to pilot error.

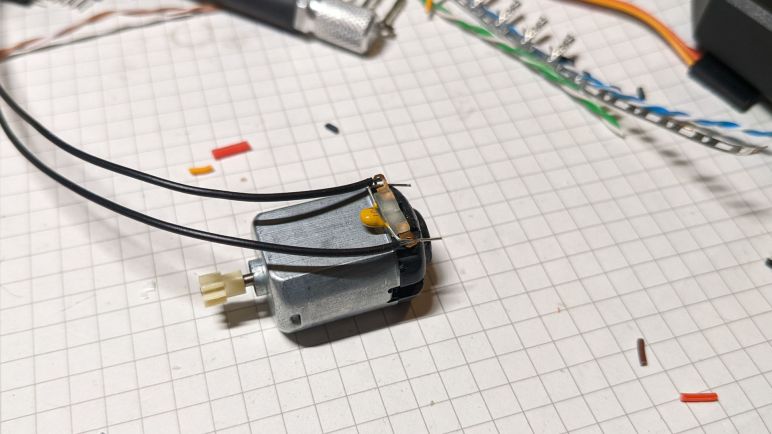

Here is the top side of the receiver. Marked with the year 2008, it reminded me how long it’s been since I played in this hobby. Looking over the components, I was not surprised by capacitors to buffer power input and the oscillator to maintain accurate frequency. There is a large IC clearly in charge of the operation, but it is unmarked. We do see an array of five pins marked J1 that looks like a debug header, but I’m not terribly interested in poking into this chip right now. The output signals pins were a surprise. I had expected some sort of a transistor array to let the main IC toggle signals on and off at the same output voltage as the input voltage. However, all I see are little resistors (R2 – R5) implying they are merely there to limit current draw on IC output pins. This is worth following up.

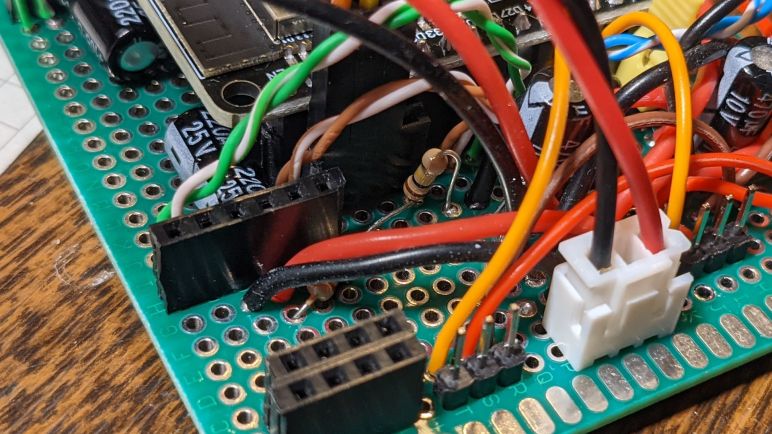

The back side of the circuit board confirms power and ground pins are connected in parallel across all output pins, with the four signal pins separate as expected. I see a lot of surface imperfection here. It looks like corrosion which might be reaction to the dirt that has been trapped in here. It may also be something from the factory, possibly excess soldering flux that was not cleaned up. I also see a sticker marked ST104M but I have no idea what that represents. Maybe a firmware revision number?

The circuit board was interesting, but for today they were merely a side show. I just wanted it out of the way as I cut into the enclosure. With the PCB removed I could confidently wield my blade, and the little wedges were quickly removed.

The receiver reassembled easily, and a quick test confirmed I could now plug in and use generic micro servos (or other devices) without interference from those now-gone little wedges.