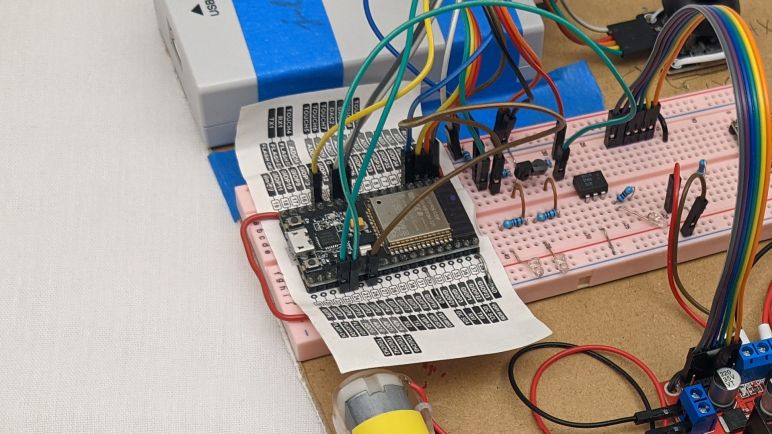

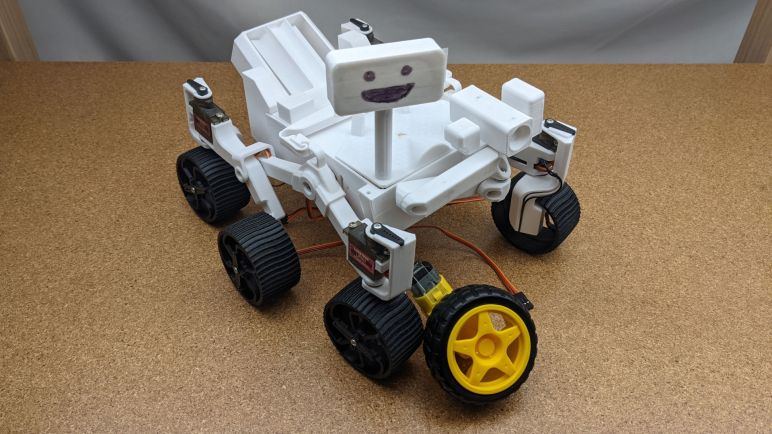

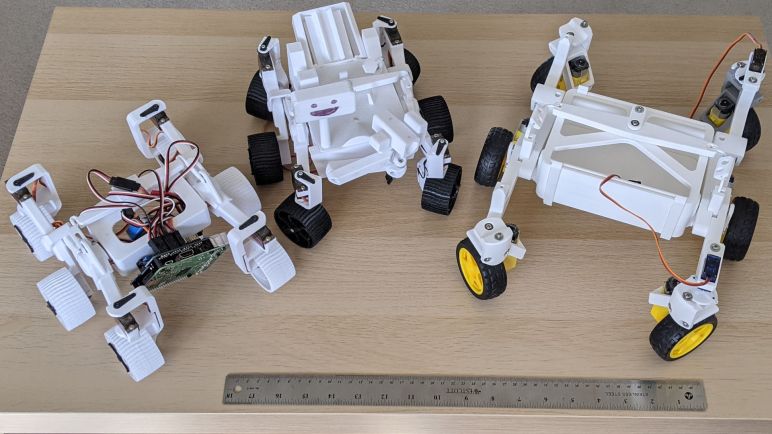

Every time I revisit the task of writing Sawppy rover control code, I’m optimistic that I’m one step closer to not having to rewrite from scratch again. This time around, I’m following conventions set by decade-long development of ROS (Robot Operating System) but writing in low-level C code that should run on anything from embedded microcontrollers on up. This approach adds a few challenges but I hope it’ll be more adaptable to other platforms (both software and hardware) in the future.

On the hardware front, many robot chassis that advertise ROS compatibility uses the velocity command (cmd_vel) topic as their interface layer to ROS autonomy logic nodes. Hardware-specific code listens to messages sent to that topic, and handle translating desired velocity into physical movement. I will follow that precedent but I also had the ambition to go one step further with some inspiration from ros_control. The key word is “had”, past tense.

As I understand it, ros_control original motivation was to interface with components that one would find on a robot arm, creating a generic interface for motors and actuators. This allows for generalized operation with ROS nodes like the MoveIt framework for motion planning, and it is also the interface layer for switching between real and virtual robots for the Ignition Gazebo simulator. And since it’s generic, it’s perfectly valid to try to apply those concept to motors and actuators for chassis locomotion.

I like the concept, but I got lost when wading into documentation. When I dug into one of the actual interfaces like JointPositionController, I saw only a setCommand() that sends a single double-precision floating point value. This is clearly only part of the picture. What is the context that number? For actuators like RC servo it would be a rotation, but for a linear actuator it would be a distance. How would I communicate that information, along with other context like whether that rotation/distance is along X, Y, or Z axis?

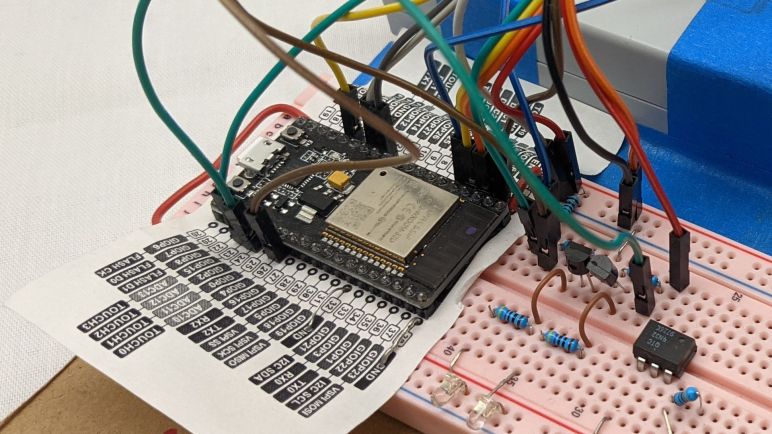

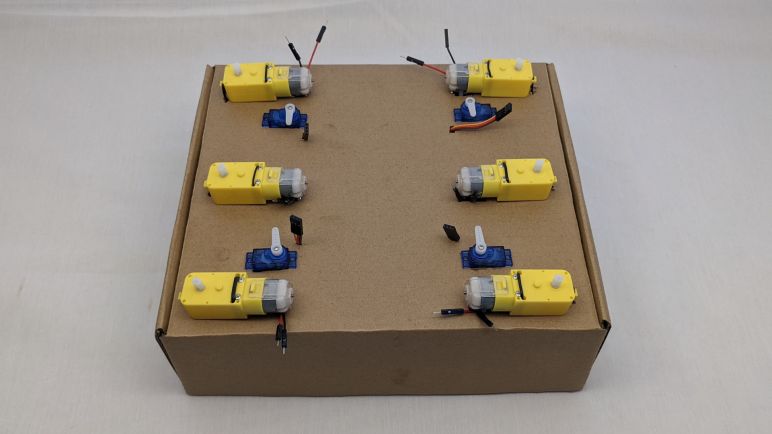

Furthermore, the interface assumes closed-loop control on every actuator, since the interface has getPosition() to query status and setGains() to adjust PID coefficients. I wouldn’t be able to offer any of that on a micro Sawppy rover. RC servos do perform closed-loop control, but the loop is closed within the servo and the robot has no visibility to actual position or adjust PID coefficients. And without an encoder wheel, TT gear motors have no closed loop control at all. Some ROS tutorials (like this one) asserted there’s no point to ros_control on low-end robots and I now understand their point.

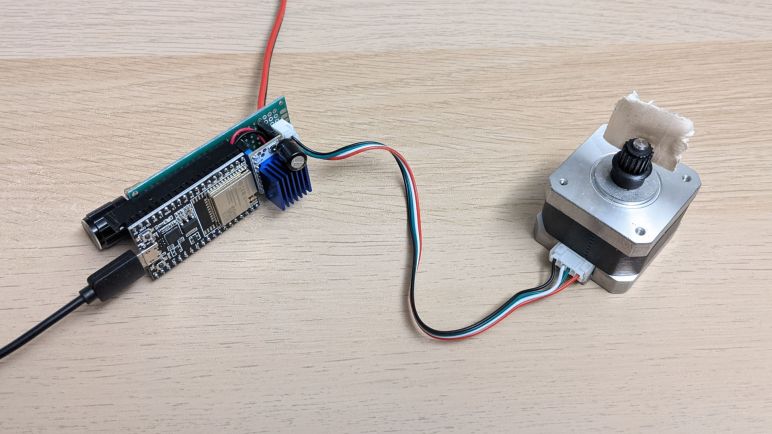

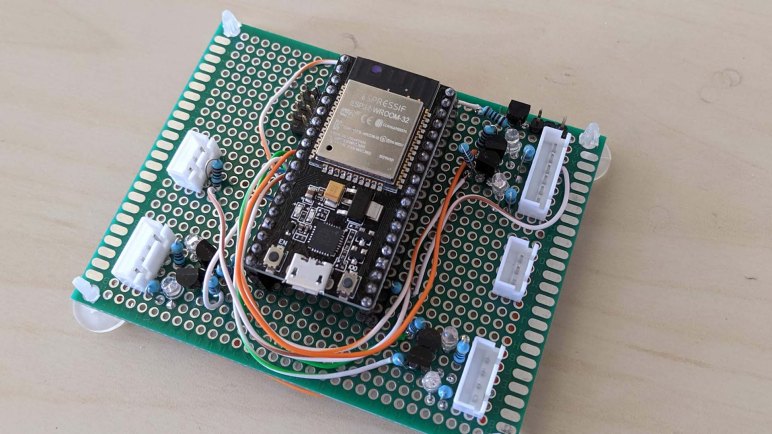

Since I don’t understand concepts of ros_control yet, I’ve chosen to postpone that idea for ESP32 Micro Sawppy software. The worst downside is that I might go down a path that will require another rewrite in the future. But hey, I’ve done it before and I can do it again. To mitigate this risk, I’ll still communicate my rover actuator commands using unit conventions as described by REP103. So I’ll communicate steering angles using radians instead of RC servo commands, which should be friendlier to conversion to different actuators in the future. Similarly, wheel speed will be communicated in meters per second rather than motor power level, again in the hopes it’ll be generic enough for other actuators in the future. Today I’ll pack them into a single message for short term ease and deal with that problem later. I have a more immediate problem: I found the TT gearboxes have a narrower range of speed than I originally thought.