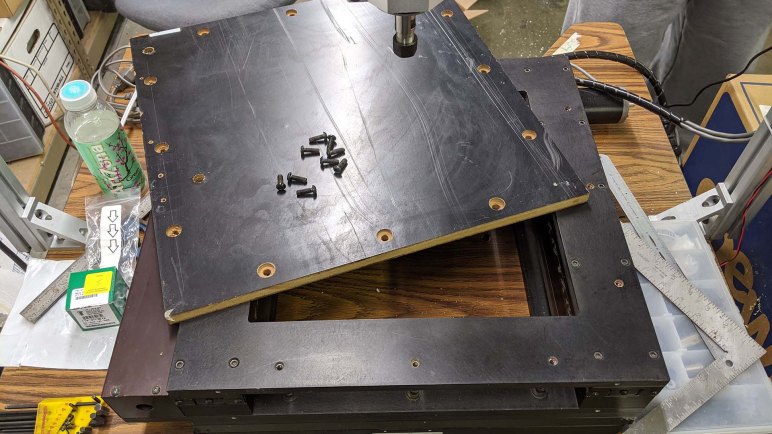

Once some convenience accessories are in hand, we return to the main business of cutting material. Our biggest unknown at this point is our spindle’s maximum speed measured in revolutions per minute (RPM). This is a critical part of calculating the “speeds and feeds” of machining. Yes, we’re cutting MDF which will be relatively forgiving, but the point of learning is to practice doing it right.

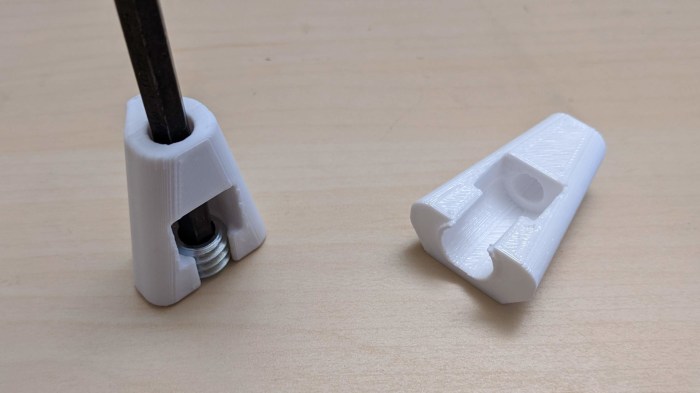

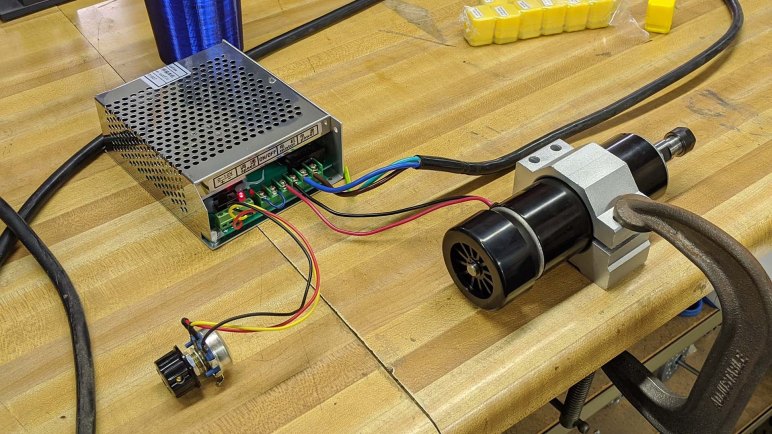

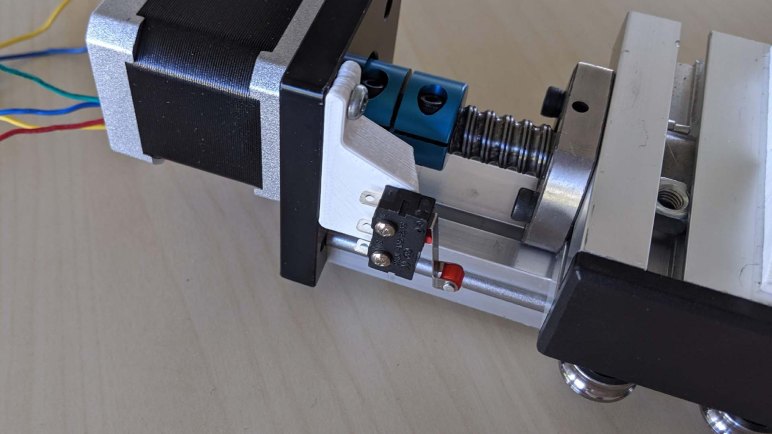

Our cheap ER11 spindle’s product page(*) claimed a maximum speed of 12,000 RPM, but we knew better than to take that at face value. To measure its actual performance, we wanted some sort of non-contact photo tachometer(*). This particular unit was on hand and originally designed for measuring remote control aircraft propeller speeds, and it measured the maximum speed at 11,100 RPM. We’ll use 11,000 RPM for our initial calculations. Later we’ll measure while it is cutting and see how much its speed drops.

Is this fast? Well, “fast” is always a relative thing. Most people’s daily experience with RPM is on their car’s dashboard tachometer. In that context it is fast as 11,000 RPM is faster than most normal car engines, though race cars and motorcycle engines can hit that speed. For machine tool purposes, though, this speed is considered on the low side. Especially for small diameter tools that we’ll be using. Physically, we are limited by the small ER11 collet for our tool diameter. Plus the machine is not rigid enough to swing a big cutting tool without flexing. And now we know the limitations of spindle speed. Which of these limitations will be the one to actually constrain what we can do with the machine? Let’s have another cutting session and find out.

(*) Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.