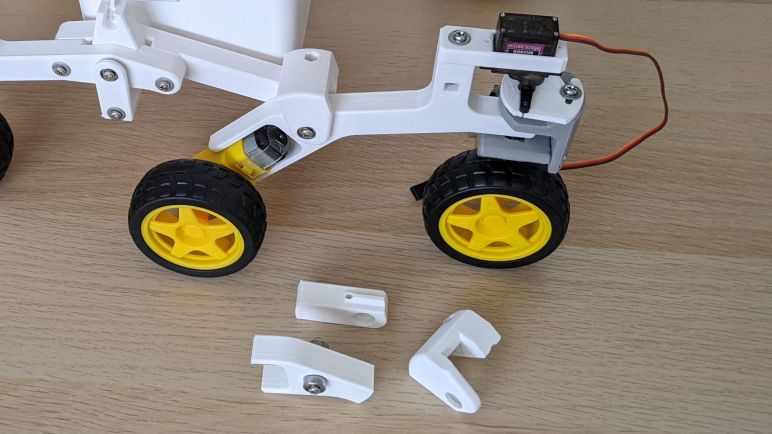

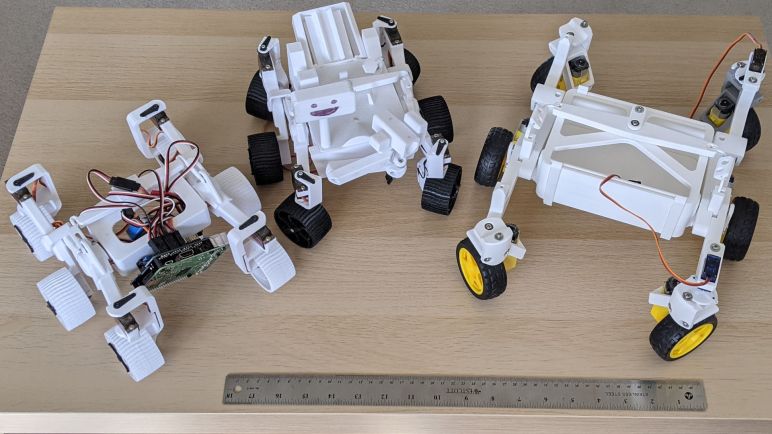

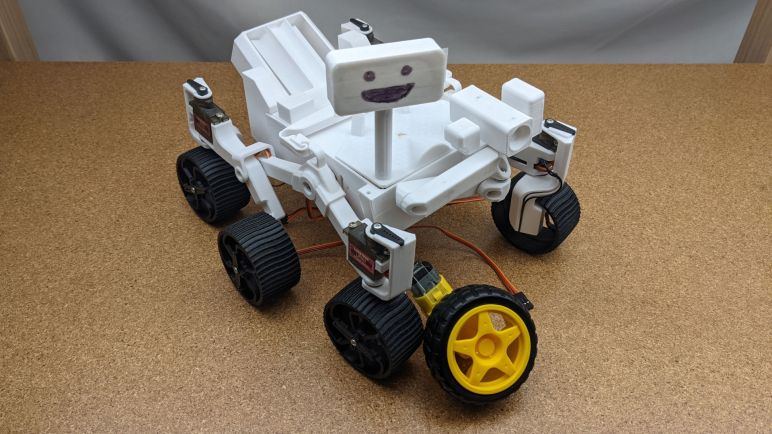

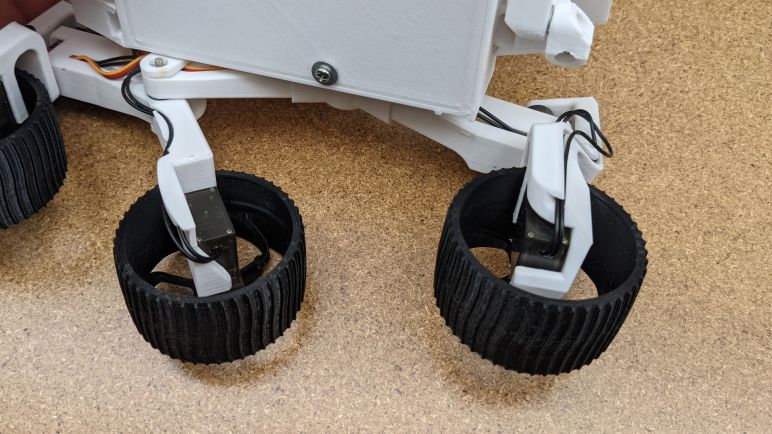

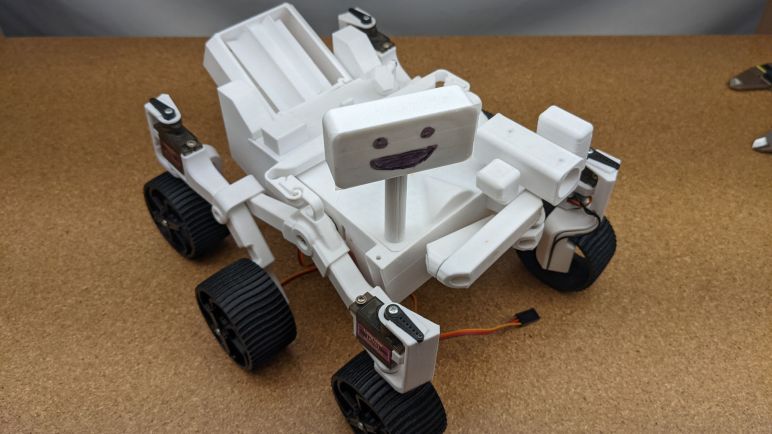

Several design changes in Micro Sawppy Beta 3 (MSB3) allowed me to experiment with different suspension rocker designs: the multi-piece rocker with deployment pivot and the single-piece rocker for straightforward assembly. One of those enabling changes was a rework of the link between the rocker and the differential, continuing the experiment started with MSB1 and MSB2 of using 3D printed living hinges for this critical linkage.

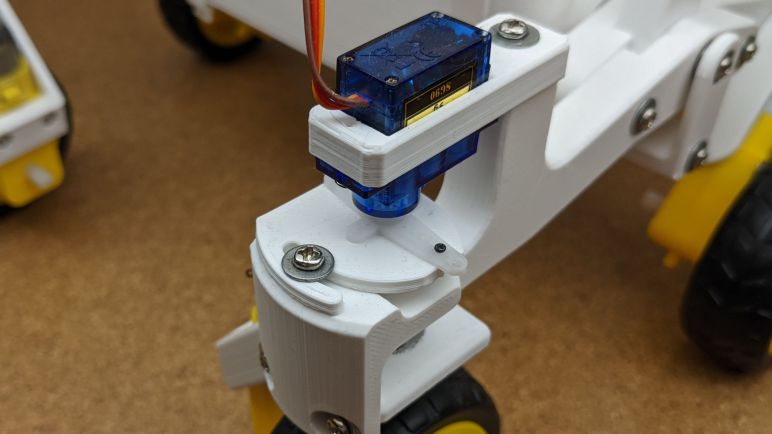

Enabling a single-piece rocker was not an explicitly goal of this rework, that was just a convenient side effect that I took advantage of. The real focus of this iteration was to make the living hinge itself a small disposable component that can be easily replaced. Because micro Sawppy is targeted for an audience with entry-level printers, I can’t assume rover builders can print with flexible filament like TPU. So if I want to use living hinge in my design, I have to account for the fact that beginner-friendly 3D printing materials like PLA will fatigue and break with some regularity.

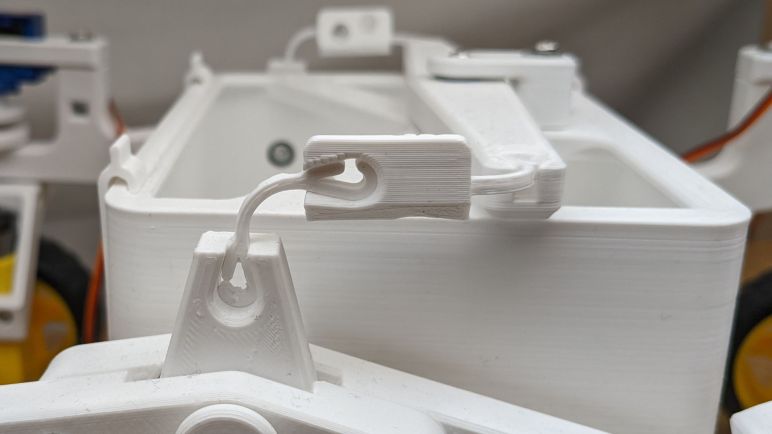

If the living hinges of MSB1 and MSB2 should break, it would mean reprinting and replacing some very large parts. In contrast, MSB3 hinge is a tiny little part that clips into larger surrounding rigid parts. Furthermore, it is the same part at all four joints. We would only need to keep one style on hand in replacement inventory, which can be used to fix any of the four joints that might break.

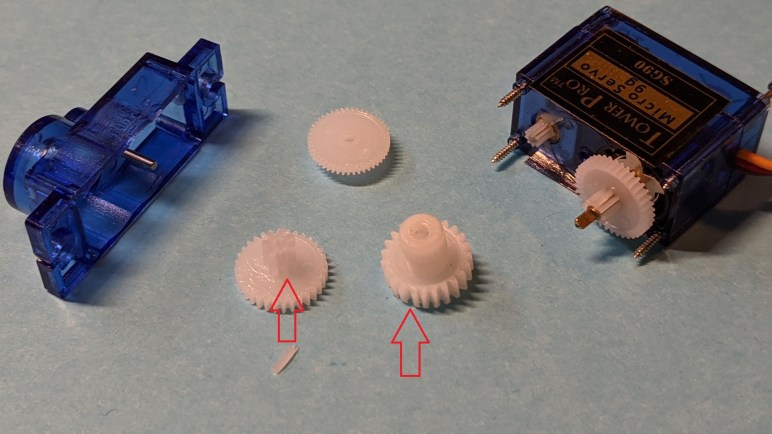

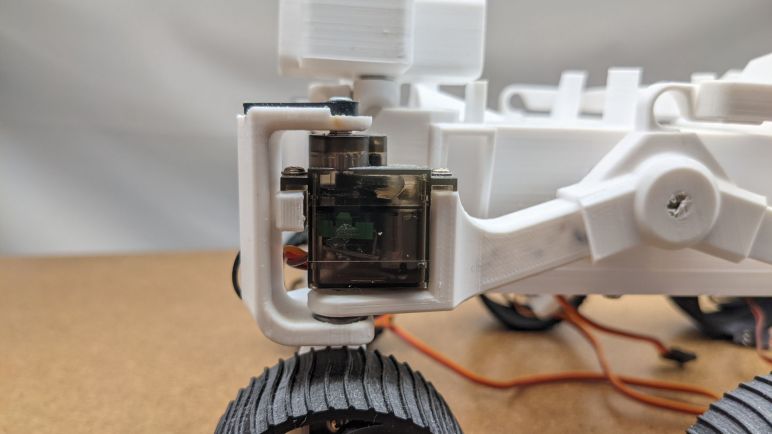

An associated benefit is that we can print the hinge with different settings to find the best tradeoff between flexibility and durability. Looking at the hinge in the orientation on the 3D printer bed, it is easy to scale the design’s print height and test how a particular batch of filament behaves. I printed these at heights varying from 2mm to 6mm and I tried the 2mm first. It would be the most flexible, and I wanted to see how long it would last.

The answer: less than 30 seconds! Oh well, at least now I know. For this particular type of material (MatterHackers Build Series PLA) 2mm was too fragile. 6mm was overly rigid and interfered with proper rocker-bogie operation. 4mm seems to be sufficiently durable but it was still too stiff to let the rocker-bogie operate as smoothly as I like. Even though these data points weren’t terribly encouraging, I’m glad MSB3 made it really easy to adjust this particular parameter for experimentation.

But at this point I’m suffering from rover fatigue and need a break. I’ll return to micro Sawppy later (UPDATE: it is later) but right now I’m going to go play with Unity 3D for about a week.