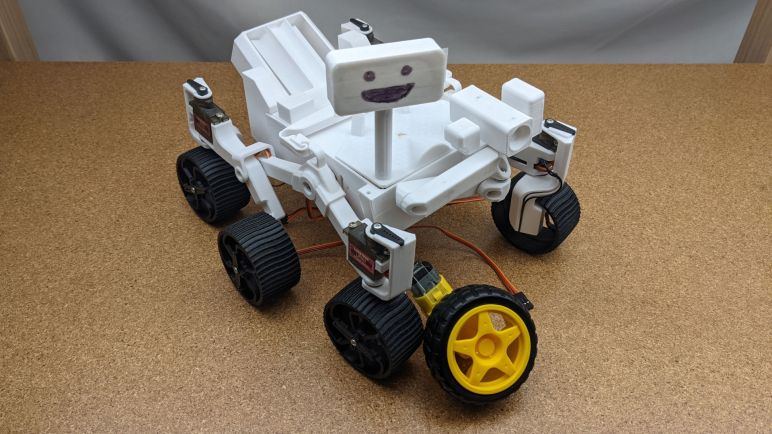

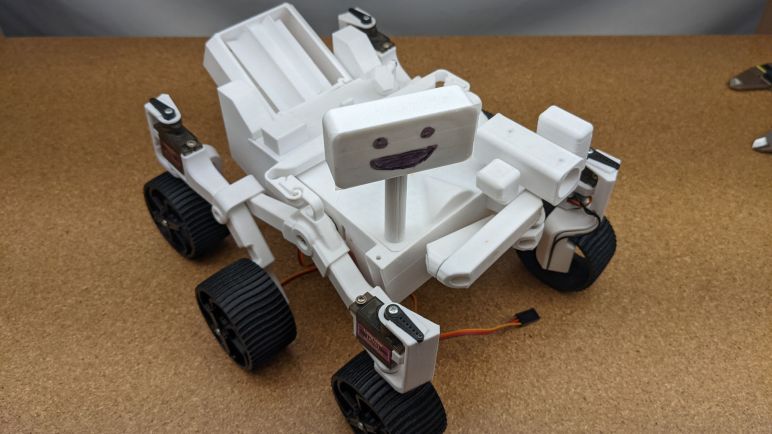

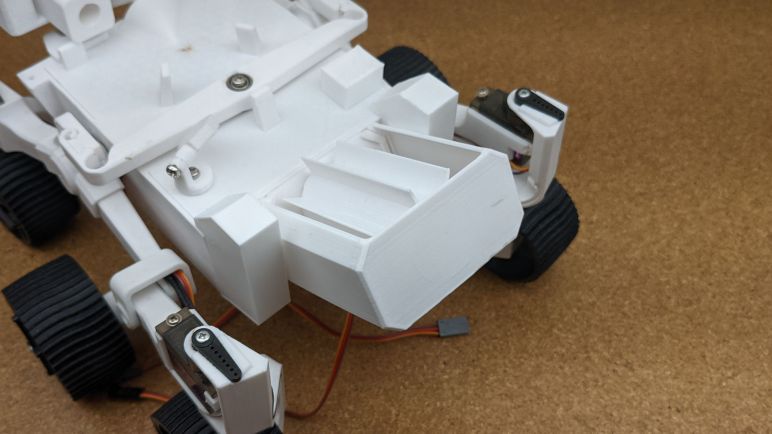

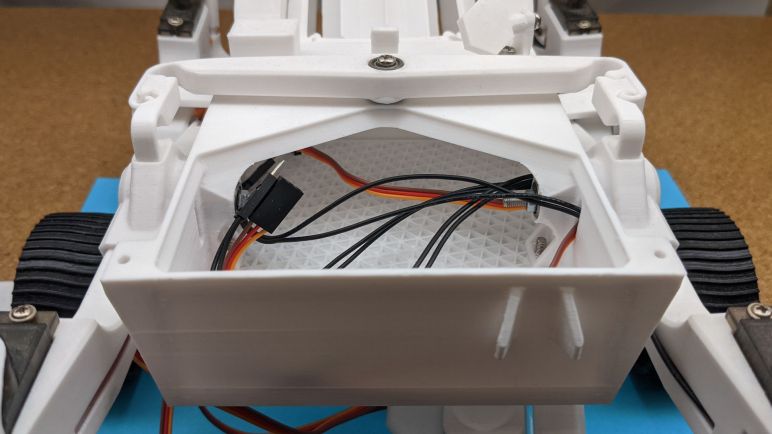

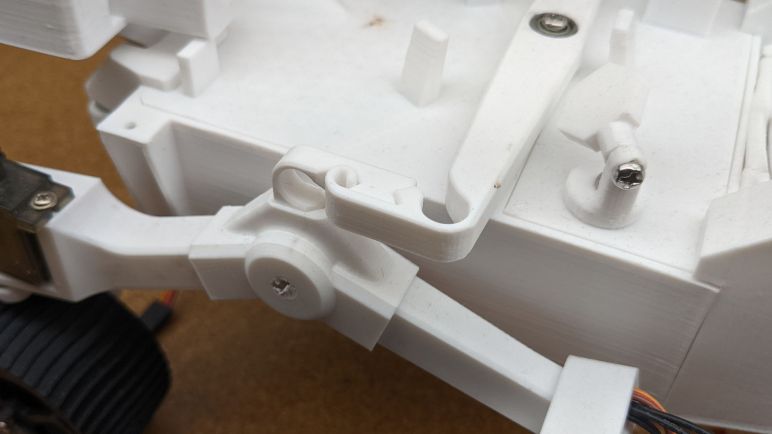

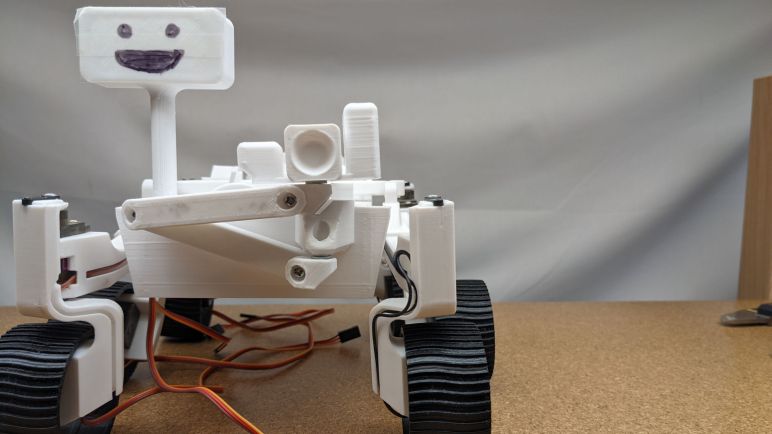

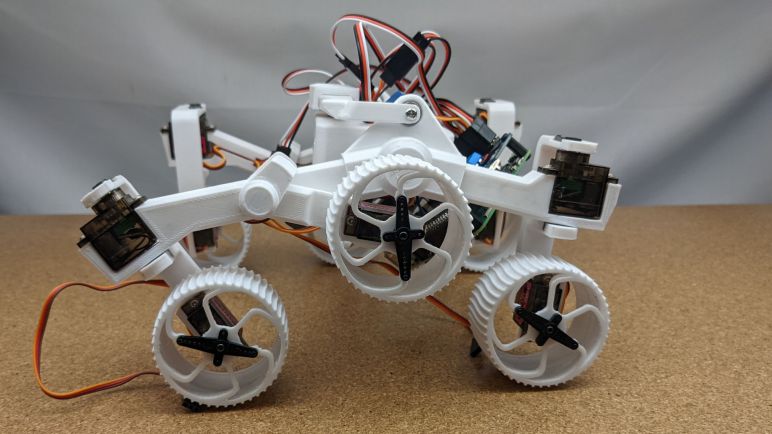

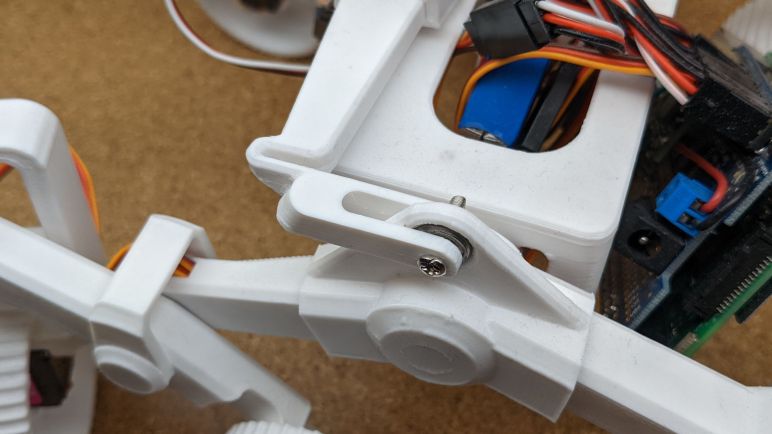

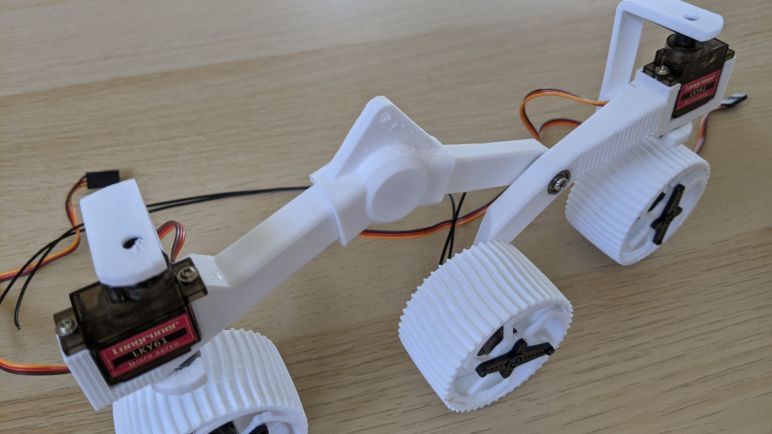

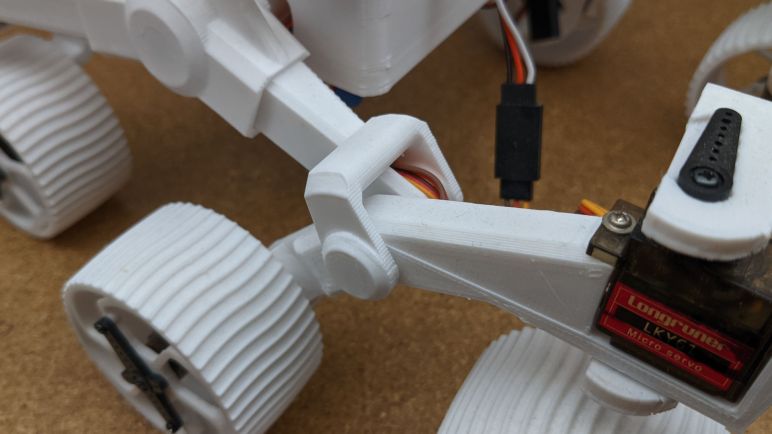

Based on my experience modifying wheel drive motors on my little rover Micro Sawppy Beta 2 (MSB2), I decided it was trending towards a rover design that would be too difficult to work on. If I, as the designer of MSB2, am tearing my hair out struggling with wire routing, how can I realistically expect beginners to work with this thing? I think MSB2 succeeded at being really cute, unfortunately the beauty was only skin deep and its core difficulties are not what I want.

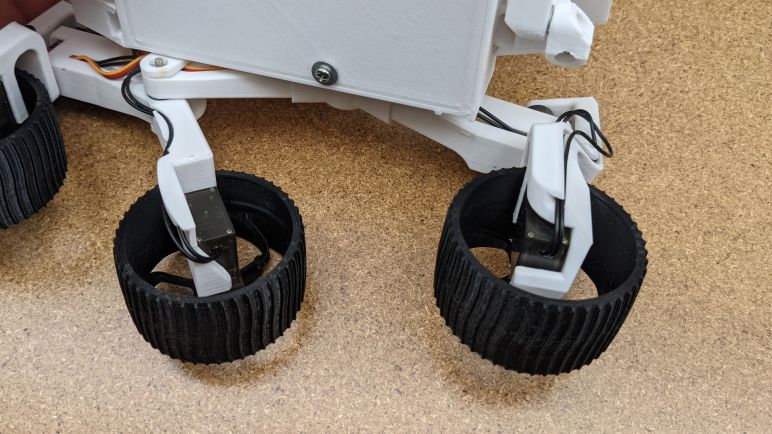

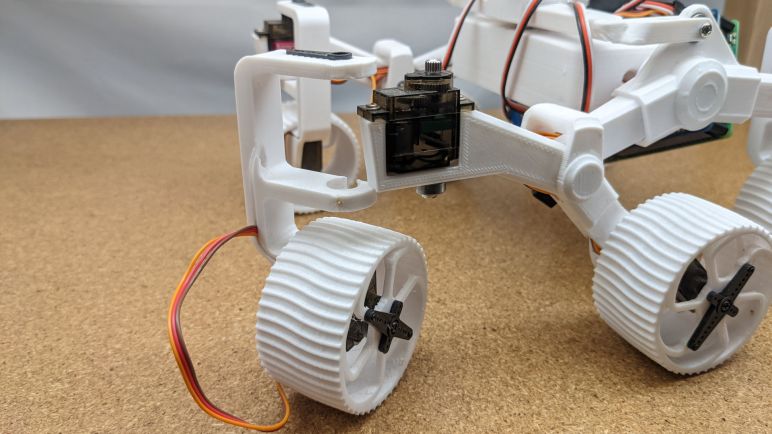

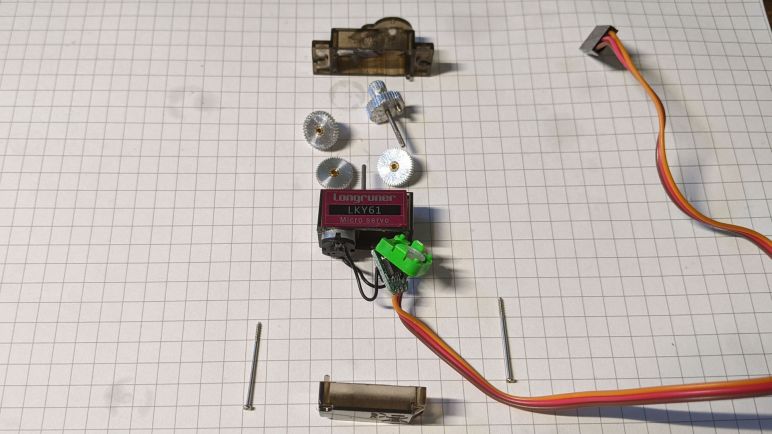

But while I stopped further work on MSB2, I wanted to continue the task I was in the middle of: trying out the idea of using DC gearmotors. The micro-servos I used in MSB2 taught me that my original idea for driving little rover wheels were unreliable. While we could modify micro servos for continuous rotation, there’s no guarantee their control circuits would give us usable speed control. Sometimes they don’t! In order to guarantee a little Sawppy rover could be reliably built, I must take motor speed control into my own hands.

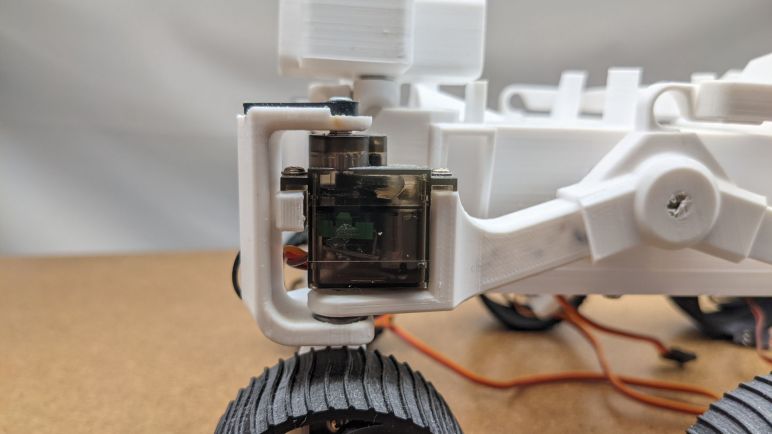

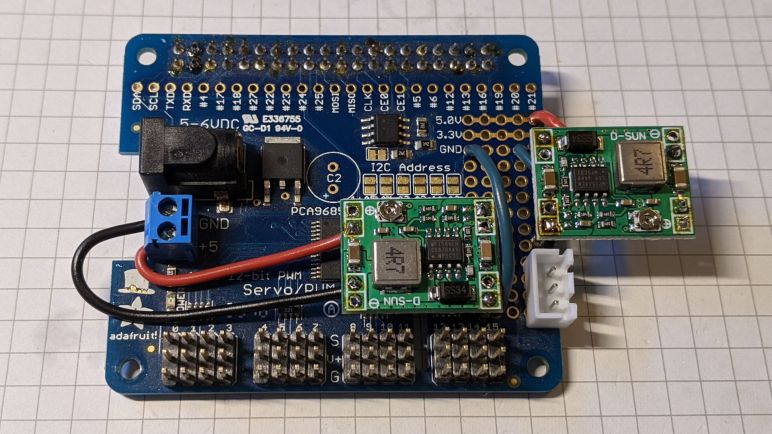

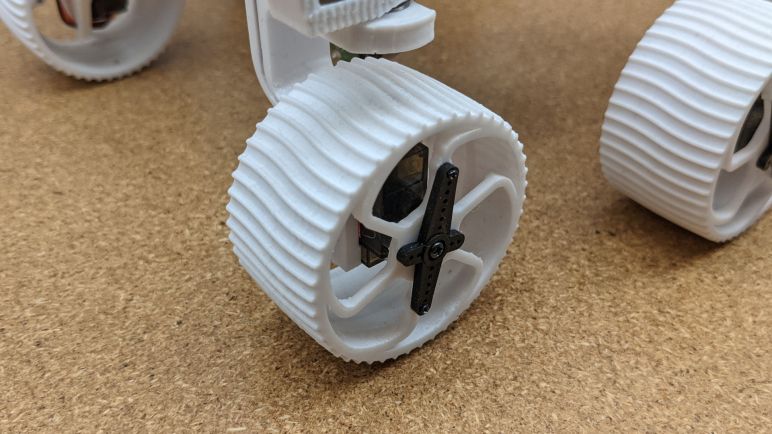

This decision started when I removed all electronics from MSB2 wheel servos, using them as just a motor with a gearbox inside a micro-servo sized enclosure. (FYI Adafruit product #2941 is exactly like this, no modification required.) Even though I’m throwing out half the device, it’s still a very inexpensive way to obtain a small DC gearmotor thanks to the large volume market of generic commodity micro servos. But if we are going to use a small high volume commodity DC gearmotor to drive little rover wheels, there’s actually a better option: TT gear motors.

These DC motor + gearbox units are ubiquitous like generic micro servos, mass produced by many manufacturers at high volume and low cost. It is available as Adafruit #3777 but they are definitely not the only retailers. (*) I first learned they existed when I saw them pop up in multiple projects submitted to a Hackaday contest, and a little background research unveiled how widespread they were.

Since I’ve decided to add the complexity of DC motor driver modules, these TT motors immediately jump to the top of the list. Unlike micro servos, TT gear motors were designed for driving wheels.

(*) Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.